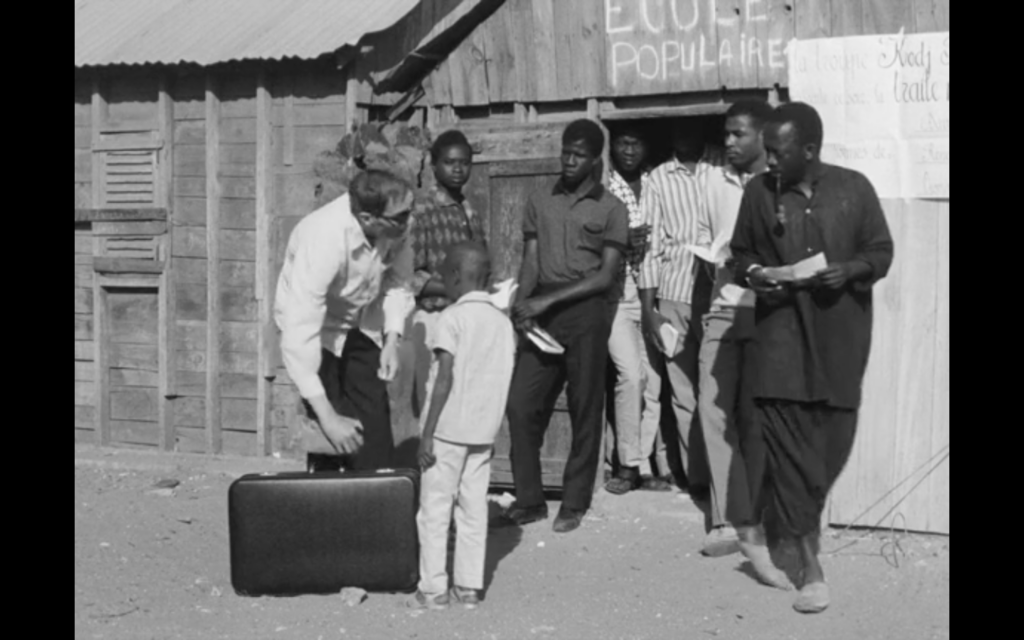

Ousmane Sembène, with his pipe, interprets a secondary character, a professor of a “popular school,” in Black Girl (1966). Cinema appears as an instrument to raise “people’s awareness.”

Ousmane Sembène (1923-2007),1 Senegalese filmmaker and writer, is one of the most striking figures in African cinema. His work emerged in the aftermath of Senegal’s national liberation from French colonial power and sought to critically analyze the contradictions of the present by uncovering lines of continuity and break with the past of pre-colonial and colonial Africa. His cinema reflected through artistic means the complex history of Africa and its peoples and communities. Sembène paid particular attention to the persistence of colonialist and imperialist ideology and structures beyond the colonial period. Going through his films, in conjunction with his discourse in interviews and lectures, an idea stands out: that culture (of which art is a part) cannot be abstracted from its historical roots and the human consciousness that produces it and it is produced by it.

Born in 1923 in Casamance, southern Senegal, Sembène spent his first years as a fisherman. In 1942, during World War II, he joined the Free French Army, an episode that deepened his understanding of colonialism and served as autobiographical material in his later work—see Camp de Thiaroye (1988). In the 1950s, Sembène became a docker in Marseille and a member of the French Communist Party. During this period, he taught himself to read and write in French. His first novel Le Docker noir (Black Docker), based on his experiences in Marseille, was published in 1956. Around 1960, Sembène developed an interest in filmmaking. For the filmmaker, cinema was a more effective instrument of political action than literature, allowing, in his words, “to change the balance of power… by raising people’s awareness.”2 After studying at Moscow’s Gorki Institute under Soviet directors Mark Donskoy and Sergei Gerasimov, he returned to Senegal and directed Borom Sarret (1963). After his first feature film, Black Girl (La Noire de…, 1966), and until his death in 2007, Sembène built an influential cinematic and literary œuvre.

There are only a handful of studies on Sembène’s cinematic body of work.3 They usually adopt the same structure: the analysis of his films in chronological order. This dossier tackles his work and legacy more deeply, concentrating on how his cinema articulates issues around colonialism and history, politics and culture, and aesthetics and film. Sembène expressed his observations in fiction films instead of documentaries, embracing the African tradition of telling and transmitting stories that creatively reflect the circumstances of a people. His films have strengthened the cause of liberation from colonial domination and other forms of oppression. His cinema portrayed economic, social, racial, gender, and religious tensions with a keen political awareness rooted in the knowledge of the history, culture, and reality of Senegal. This dossier analyses the (post-)colonial reality of Senegal and the historical and political demands placed upon artists according to the filmmaker. It also addresses Sembène’s vision of culture as embodying the condition of being human, as he conveyed in a lecture at Indiana University-Bloomington in 1975 and demonstrated in his own creations. Moreover, it closely connects these aspects with his filmmaking style, an element of his work that has been neglected in existing studies.

It is the first major study on Sembène since the resurgence of interest in his work, following the release of Sembene! (Samba Gadjigo and Jason Silverman, 2015) and the restoration of Black Girl (La Noire de…, 1966) by The Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project, founded and chaired by Martin Scorsese, in 2016, and recent retrospectives in film festivals. Current discourses around post-colonialism and engaged cinema, along with approaches from different fields of knowledge, provide new ways of reading and understanding his films. This group of essays engage with current discourses around post-colonialism and militant cinema that provide fresh perspectives on Sembène’s work. They offer scholarly and critical approaches from the fields of African studies, ethnographic studies, film studies, gender studies, literary criticism, religious studies, among others. They also combine close textual analysis with detailed contextual examinations to argue for the artistic and political significance of Sembène’s work.

In general, this dossier reaffirms Sembène’s importance as an African filmmaker and politically engaged artist. The process of “gaze’s shift”4 permeates all of these contributions and it has important repercussions at the representative and epistemic levels. In The Predicament of Culture. Twentieth-Century Ethnography, Literature, and Art, James Clifford argues that the aesthetic-anthropological opposition is systematic.5 According to the author, since the early years of modernism and cultural anthropology, non-Western objects and subjects were inscribed either within the discourses of art or within those of anthropology. In the framework of the culture of transnational liberation of the 1960s and 1970s, in which political decolonization was perceived as inseparable from the decolonization of culture, art, and knowledge, Sembène’s filmography operates a synthesis between modern and traditional elements, pointing to the possibility of non-exclusion and integration of the aesthetic and anthropological domains. This process is inseparable from a rotation of the gaze from the former colony, Senegal, to the ex-metropole, France, in films such as Black Girl and Mandabi (1968). In “Black Orpheus,” Jean-Paul Sartre affirms that “the white man has enjoyed the privilege of seeing without being seen.”6 Later, in the foreword to Frantz Fanon’s The Wretched of the Earth, the French philosopher calls to a process of gaze’s rotation: “Let us look at ourselves, if we can bear to, and see what is becoming of us.”7 These essays demonstrate that Sembène’s work operates such an inversion of the colonial gaze, through the processes of organization of the point of view as well as the multitemporal and multispatial polyphonic narrative construction of his films.

Raquel Schefer & Sérgio Dias Branco

- Regarding the order of the filmmaker’s name, see Sérgio Dias Branco, “Sembène, Ousmane (1923-2007)”, in The Palgrave Encyclopedia of Imperialism and Anti-Imperialism, Vol. I, ed. Immanuel Ness and Zack Cope (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016), 219-220. ↩︎

- Guy Hennebelle, “Ousmane Sembène” (interview), Jeune cinéma, 34, 1968: 5-6 (our translation). ↩︎

- See Françoise Pfaff, Cinema of Ousmane Sembène: A Pioneer of African Film (Wesport, CT and London: Greenwood Press, 1984); Shelia Petty, ed., A Call to Action: The Films of Ousmane Sembène (Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger, 1996); Sada Niang, ed., Littérature et cinéma en Afrique francophone: Ousmane Sembène et Assia Djebar (Paris: L’Harmattan, 1997); David Murphy, Sembène: Imagining Alternatives in Film and Fiction (Melton: James Currey, 2000); Samba Gadjigo, Ousmane Sembène: The Making of a Militant Artist, trans. Moustapha Diop (Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 2010); Amadou T. Fofana, The Films of Ousmane Sembène: Discourse, Politics, and Culture (Amherst, NY: Cambria Press, 2012); Lifongo J. Vetinde and Amadou T. Fofana, eds., Ousmane Sembène and the Politics of Culture (Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2014); Ernest Cole and Oumar Cherif Diop, eds., Ousmane Sembène: Writer, Filmmaker, and Revolutionary Artist (Trenton, NJ: Africa World Press, 2015). ↩︎

- Fredric Jameson, The Cultural Turn: Selected Writings in the Postmodernity (London and New York: Verso, 1998), 107. ↩︎

- James Clifford, The Predicament of Culture: Twentieth-Century Ethnography, Literature, and Art (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1988). ↩︎

- Jean-Paul Sartre, “Black Orpheus,” trans. John MacCombie, The Massachusetts Review 6, no. 1 (1964-1965): 13. ↩︎

- Jean-Paul Sartre, “Preface,” in Frantz Fanon, The Wretched of the Earth, trans. Richard Philcox (New York: Grove Press, 2004), lvii. ↩︎