In Ousmane Sembène’s 1966 film, Black Girl (La Noire de…), an indigenous mask percolates persistently between the film’s white and black bodies. As one scholar of African art has suggested, “Masks pose vexing questions for museum curators, not only as an uncomfortable legacy of colonial collecting practices, but because they inevitably suggest an absence.”1 The mask in Black Girl is deployed in just this dually vexing way: to indicate an unreflective colonial practice of collecting ‘authentic’ indigenous artifacts, and to signal the pressured presence of a series of absences (e.g., bodies, nations, values, hopes). In this way, the mask dramatizes what Bill Brown has termed “the problematics of otherness.”2 In this essay I approach the mask as a religious object, both because of what it signifies on the level of content in terms of identity, sociality, and idealized values, and because of the transcendence I see it enacting through the formal geometries of cinematography.3 The transcendence of the mask—positioned in the mise en scène as looking on and judging the actions of the film from its edges—is mirrored by the transcendence of viewers positioned as looking at the action through the eyeholes of the camera, so that the film can be seen as events occurring between these two masks (the camera and the indigenous object). Sembène uses the mask as a visible disruption that comments on the various characters and their worlds and drives home the lived, affective states produced by white privilege: disjunction, dispossession, resistance, dissent, and despair.

To put this last point more philosophically, the mask shows up the limitations of phenomenology in the vein of Maurice Merleau-Ponty in that the film insists that the seeable and the sayable of a body and its world are not in a harmonious and reversible chiasmus but are always in a relation out of phase with itself, like the conflicting but juxtaposed planes of a Magic Eye picture. To cite Brown again, Sembène’s mask pressures viewers to reflect on “how objects mediate our sense of ourselves (as individuals and as collectivities) and our sense of others.”4 This essay attempts to demonstrate how the film’s mask functions as both transcendent witness to socio-political injustice and transcendent repository of religious and cultural values. By depositing ‘religion’ in a material object (the mask) by means of a cinematic function (transcendence), Sembène’s Black Girl enacts religious critique in two ways: first, in reminding viewers of the difference between ethical-religious values and market values; and second, in exhorting response to colonial exploitation of labor, decolonial exploitation of women, and the death-dealing indifference of racism.

Sembène and Religion

Sembène (1923-2007) is most often tagged as the father of African cinema, even though he initiated his professional career as a novel writer. His life experiences of serving in the French colonial army in WWII and working on the docks in Marseille galvanized his political activism and initiated a serious study of Marxist theory. After publishing such well-received novels as The Black Docker (Le docker noir, 1956)and, especially God’s Bits of Wood (Les bouts des bois de Dieu,1960), Sembène found himself showered with friendship from many of France’s literary elite, including Jean-Paul Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir, Louis Aragon, and black intellectuals such as Aimé Césaire, Léon Damas and Ferdinand Oyono. This brush with fame was recontextualized by his 1961 return to Senegal, when Sembène realized that the less literate populations of Senegal (and other African countries) had little to no access to his novels. Seeking the advice of Parisian filmmakers, he applied to a number of countries for financial aid and received support from the Soviet Union, which he had visited briefly in 1957. He spent 1962 studying film at the Gorky Institute in Moscow and released Borom Sarret (The Cart Owner) in 1963. Although Sembène had discerned that film would be inherently more accessible than novels, he did not anticipate the distribution difficulties he would encounter when political factions accommodating to Western influence and Western aid resisted the leftist orientation of his films.5 His life and work express a fervent attachment to the poorest and most marginalized sectors of post-colonial society and to the desire for African peoples to self-govern without Western influence or assistance.6 His desires, however, are not programmatic. His films and novels push viewers and readers toward notions of ethics, autonomy, citizenship, and African statehood, but the exhortations are as contentless as they are urgent. How can Senegal or a Senegalese citizen be ‘autonomous’ within the current geopolitical situation of Western extraction of African resources, Western food-aid to African states, and the sedimented legacies of colonization? The question is crucial, central, but also impossible to resolve.7

In Black Girl,what I take to express Sembène’s ‘religion’—that is, his concern to promote robust life (and not merely survival) and to critique forces that obstruct or obfuscate the fullness of life—is decidedly projected into abstract idealizations that are inverted into the material object of the mask. The film’s mask is thus literally a fetish, an object that simultaneously expresses and suppresses the social, human and collective production of those cherished values concerning human being, social collectivity, and political possibility. We might be tempted to say that Sembène’s is a religion of Humanism, but not only is that an unhelpful cliché, it also is incorrect. Sembène carried out a decade’s long struggle against what he perceived to be the homogenizing and domesticating “Pan-Africanism” of Leopold Senghor. The latter’s “Negritude” movement associated the iconography of masks with a common African “heritage,”8 that is, it asserted the equality of all Humans and posited difference as overcome through a recuperation of the positive accomplishments of ancient History. The use of the mask in Black Girl, however, suggests that it is not heritage but situation that conveys the most important commonality among African peoples. The mask does not represent the history or essence of Africa but congeals values and hopes that stand in contradiction to Senegal’s post-colonial condition, with the on-going asymmetries of personal and political control, voice, and economic self-determination that exist between African states and their former European colonizers. The mask presents Brown’s “problematics of otherness” shared in and between African nations by skirting particular historical claims and focusing on general structures of social relationships.

Abstract Possession

Black Girlis a film conscious of geometry, that is, of shapes set repetitively by camera position and angle, as if Euclidean rationality could immobilize—like pushpins holding papers to a bulletin board in a windy room—the wafting, traumatic chaos of racism, colonialism, and human desperation. The visible disruption—what Meleau-Ponty would call the écart (opening, divergence)—that shifts this Euclidean immobility to phenomenological topology is the oblong African mask. Positioned to mark asymmetry, the mask tips the film’s stable geometry into a dynamic and lived topology by its constant and disjunctive presence. Like any religious icon, the mask locates, focuses, and magnifies what C. S. Peirce would call vague sets of identities, practices, and values.9 These vague value sets establish meaning in the bodies that love them precisely by transcendingthose bodies—by remaining external to and in excess of any particular body. Indeed it is only as a point of transcendence that the mask can function topologically to interrupt the various relationalchiasms caught by the film’s cold, Euclidean geometries. Disjunctive to the ‘balanced’ perspective of the relational geometries, the mask comments on the imbalance — the inequities — inhering within those chiasms, thus showing through film form how the mask functions topologically as a transversal interruption of the various character relationships framed by the film’s cold, Euclidean geometries. To cite Brown again, the mask “mediates our sense of ourselves (as individuals and as collectivities) and our sense of others.”10 The mask is a social object, abstracting from the institution of meaning and value in any particular body into a shared religious artifact, thereby enabling the object to present the specific historical structure of French-Senegalese colonialism and to abstract from this specificity in order to evoke and condemn the perduring structures of racial, gender, class and imperial oppression.11 In short, the mask’s religious function can be seen in its constellation and condensation of desires that are not (yet) incarnate, desires for religious and ethical norms that oppose the colonial and postcolonial values of the labor market and of indigenous patriarchal power. The mask thumps out the bodily urgency and social possibilities of those desires by forming the central but transcendent visual axis of the film’s human relationships.

At once universal and historical, then, the film’s algorithm of oppression runs a steady course to the bloody death of its title character. As the French title underscores, Diouana is not just a black girl. She is someone’s black girl, la noire de… The possessor is not named in the title, a fact that renders the formula universal and disconcertingly inevitable: Diouana cannot be a black girl except by being someone’s black girl; she cannot be seen without being herself rendered an object to be bought and sold. The conjoined channels of materiality that I want to examine in this essay are thus the immobilizing geometry of cinematography that renders Diouana an owned thing, and the mask’s immobilizing abstractions of meaning and value that dissolve her reification into a swampy mess of despair. To do so I will draw on Merleau-Ponty’s claims about cinema and the phenomenology of perception. But first, a brief outline of the film’s plot.

The physical arc of the film begins in France, and ends in Senegal. But the narrative structure relies on two flashbacks, so that the film traces three spirals—from France to Senegal to France to Senegal to France to Senegal. Straightening out these kinks, here is the story. A young Senegalese woman desperately seeks employment from “the whites.” After being refused at the doors of the many colonial apartments in Dakar, she takes the advice of her soon-to-be-boyfriend and hangs out on a street corner with other young, black women, waiting for the white wives to come and select their nannies and housemaids. When Diouana is hired as a nanny, she gleefully buys a mask from her younger brother as a present for her new employers, who remain unnamed in the film. She enjoys her work as a nanny in Dakar, and is excited to be asked to travel to France to meet the family in the French Riviera. Once in Antibes, however, the children are away and she is expected only to cook and clean. She hates her work and barely communicates with the white couple. The camera never shows her outside the small, boxy apartment. As she labors she keeps up a steady internal monologue about her life and grows increasingly depressed. The Man reads Diouana a letter purportedly from her mother (Diouana’s internal voice denies it), after which she sinks further into depression. She takes the mask off the wall and into her bedroom. When the Man finally brings Diouana her salary, she holds the bills loosely and sinks to the floor crying. She and the Woman fight over the mask. Diouana then calmly returns the money, neatly packs up her suitcase, places the mask carefully on top of it, goes into the bathroom and cuts her throat in the bathtub. The scene shifts to the beach and tracks in on a sunbather reading a small newspaper blurb about Diouana’s death. The Man returns to Dakar with the mask, finds Diouana’s mother and tries to pay her Diouana’s earned income; the mother refuses the money. The brother from whom Diouana bought the mask takes it up again, puts it over his face, and follows the man back to his car. The last shot of the film is a close-up of the mask, which the boy slowly lowers to reveal his bemused face.12

Transcendence

The film is a tragedy shot in polite whisper.13 Sembène uses straight lines, rectangles and squares — the cold logic of European and Euclidean rationalism — to outline the banality of evil. Sharp angled and repetitive shapes are caught by the camera and form insistent equations that place a calm frame around Diouana’s seething desire and anchor her quiet desperation as surely as prison bars. Consider the opening shot, which clues viewers into the film’s fundamentally geometric sensibility like the premise of an argument. Moving lines cut across the plane of the screen as a huge white ocean liner glides from screen-left to screen-right, and a much smaller two-toned fishing boat cuts a transversal line from the horizontal plane of the ocean liner toward the bottom of the screen. Because both vessels are moving, the small boat ends up carving a wake in the water almost parallel to the ocean liner, and this latter vessel itself is interrupted by another, even smaller boat heading out to sea, that is, from the bottom to the middle of the screen.

Here the camera cuts to another shot of the water, and this time it is the camera (not a vessel) that moves, panning screen-right to screen-left. Instead of fishing boats, static, dark masses of land interrupt the expanse of water. In particular the camera catches a mid-screen jut of land, bordered by a dark swath of trees at lower screen and a hazy, watery channel above. Viewers barely have a moment to notice the large white ocean liner entering that channel before the screen goes black with the title frame.

The composition of this opening sequence moves steadily along distinct lines, shapes, and planes. It is an odd opening for a neo-realist or new-wave film, since it is shot in an angle uncharacteristic for those post-war genres: an extreme long shot and high-angle, “God’s eye” view. What Gilles Deleuze would term the “camera consciousness” of the opening is transcendent to the world it opens onto and reveals both the calm geometry of parallel lines and the stark dissymmetry of size, strength and color.14 This initial transcendence, enacted through the formal structures of cinematography, will soon take materialform in the mask, which also witnesses the physically parallel lives of white and black bodies, and the stark asymmetry of the distribution of privilege and opportunity. Asymmetry pulsing within putative (parallel) equality is precisely Sembène’s point; it is the frustration, concern or argument into which the mask intervenes as disruptive comment. The mask’s transcendence thus does not simply externalize Diouana’s internally held sense of self, but posits a different reality, evoking possibilities that aim at planes of existence literally outside of this film’s geometry.

Phenomenology of Film/Persistence of Religion

In 1945, Merleau-Ponty delivered a short lecture to the Institute for Advanced Cinematographic Studies15 titled “Cinema and the new psychology.”16 In it, he associates film watching with his own phenomenological account of perception, the so-called ‘new psychology.’ A passage in the penultimate paragraph can serve as a summary. Merleau-Ponty here concludes that film is unique among the arts because it presents viewers with “consciousness thrown into the world, submitted to the gaze of others and learning from them what it is. […] Cinema,” he continues, “is particularly apt at showing [à faire paraître] the union of mind and body, of mind and world, and the expression of the one in the other.”17 Cinema — especially sound cinema and color cinema — attains this aptitude in large part because its production is inherently multisensorial; that is, cinema is not just a “temporal form” of images (une forme temporelle), and not just a “temporal form” of sound, but is a moving sensorial ensemble of landscape, bodies, relationships, noises, dialogue, and music.

Importantly, this sensorial ensemble rejects any privileging of interiority. Resonant with his phenomenological account of perception, Merleau-Ponty sees cinema relying on external cues of conduct and comportment: “For cinema as for modern psychology, vertigo, pleasure, sadness, love, hate are behaviors.”18 Cinema expresses new psychology (or new psychology expresses cinema) because viewers do not passively receive and interpret successive image-signs and sound-signs, but are rather caught up in film.19 Viewers fall into a film’s mood, and intuitively, affectively, and cognitively absorb what the externally presented and moving sensoria of posture, action, modes of address, attention to self and others, attention to landscape, and diegetic and non-diegetic music all say (mean, express, imply) about human life.

This lecture was delivered rather early in terms of film history, right on the cusp of Italian neo-realism and the French new wave, cinematographic movements that sparked the critical attention of André Bazin and other critics of the late 1940s. But Merleau-Ponty’s hypotheses intrigue me as a cipher for the limits of phenomenology for film analysis. The philosopher’s analogy of film and perception seems to be correct: in fact, I am often caught up in the moods and behaviors of a film in ways that are distinctly matrixial and multiply affective. But it also seems incorrect, and the places where it seems to miss are exactly the points where I find the work of Michel Foucault more useful in my attempts to explicate cultural expressions of religion. For example, Black Girl shows us “consciousness thrown into the world, submitted to the gaze of others and learning from them what it is,” but only in the sense that this submission and lesson are constraints and limitations, the production of pressured normativity—as Foucault might argue—and not the flowering of self-knowledge, as Merleau-Ponty seems to assume. To me, this question about phenomenological analysis of film also marks the persistence of religionin cultural objects and relations: precisely because the world does not bubble up naturally into a harmonious psychological and bodily reception, and because our engagement with the world is always marked by gaps and limits, religion (in this case the religious object of the mask) persists in lived experience and aesthetic productions as the reminderof the excess of the world to my perception of it, the lived disjunction of my world from that of others, and the hope for ethical acts and dispositions that acknowledge and attenuate the gaps.

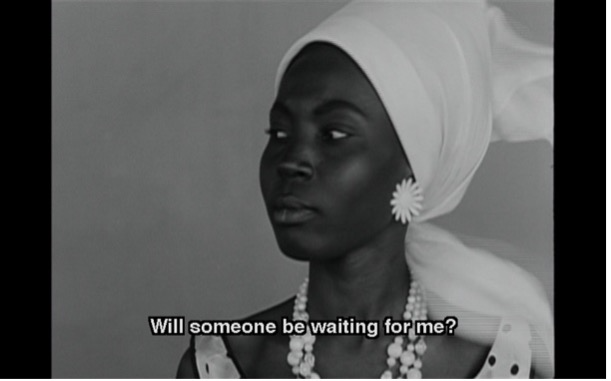

After the opening shots of ships, the camera settles on the figure of the black girl, Diouana, disembarking from the ocean liner onto French soil. Seemingly in line with Merleau-Ponty’s contention that cinema shows us externally entwined relations of harmony or unity with the world and others, what viewers see of Diouana is simply a self-possessed and fashionable Senegalese woman.

It is only because viewers are also given god-like access to her internal voice that we know how much her presentation to the world, or at least to the world of whites, is itself a kind of mask. In other words, the multisensorial experience of this film does not weave a thick ensemble that unifies mind and world, but instead presents diremption and dissonance right from the entrance of its protagonist. Black Girl shows—in fact the work of the film is to show—that the world such as Merleau-Ponty describes it, that is, as phenomenologically available and as an expected, ‘natural’ world, is so onlyfrom the point of view of those already deemed ‘normal’ or ‘natural.’ It is a world that gives little voice or attention to those who cannot find ballast within it, or to those who yield only reluctantly to hegemonic patterns of life. The visible-invisible pressures of normalization blanket our lived worlds, and the film demonstrates what the philosopher does not, namely, how historically constituted presumptions frame and interpret the world we see and thereby actually matter forth the world we can see. “It matters how we think about feeling,” Sara Ahmed asserts.20 That is, it makes a difference and it makes the objects and lived relations of our world.

In displaying the chiasm of Diouana and her world with geometric relentlessness, the film incites its god-like viewers to intuit how this intertwining fails to express the unity of her mind, body, and world, and how much it insists, instead, on the friction of her resistance. The chiasm, in other words, is shown as frayed and asymmetrical, as accruing more comfort and empowerment to some bodies (to les Blancs) than to others (to la Noire de…). The “visible and sayable” of the film are arranged according to what Jacques Rancière terms consensus, that is, the regulated (“policed”) affirmation of a distribution of a specific manner of being and feeling, a manner (i.e., dominant, French, ‘white’) that renders Diouana’s felt experience—her dissensus—invisible and unsayable.21 This dissensus counters the harmony of the film’s phenomenology, or what we might see as social status quo. Consider Merleau-Ponty’s claim (from a much later work than his lecture on film) that “I recognize in my green his green, as the customs officer recognizes suddenly in a traveler the man whose description he had been given.”22 The statement asserts a stunning congruence of experience, an assumption of a shared world that seems to leave no room for error. Reading it in our twenty-first century world of airport screenings and police profiling, in our post-Trayvon Martin, post-Eric Garner world, the claim drips with unexpected and disturbing nuance. To assume that les Blancs in the film see the same green in the meadow as does Diouana (or see the same ocean blue, or the same beauty of the French Riviera) is, the phenomenologist asserts, in line with assuming that a customs officer will spot the man described in the search notice.23 But this assumption of sameness registers as bad abstraction, as what Marx discussed as reification or alienation. If the senses themselves have an intertwined biological and social history, then surely this history accrues in different bodies differently, depending on the specificities of that history. Standing in the position to arrest is not the same as standing in the position of being arrested. The evolution of our bodies to be able to sense a colored world is also the evolution of our minds to anchor the color of objects with affect, power, privilege and position—to form expectations and anticipations, interpretations and affective protections, all in light of certain colored sensations (a red sunrise, a black thunderhead, the sparkling flash of steel, the blue of a police cruiser). Merleau-Ponty does note that a color is not a free-floating patch of sensation (what Peirce might call a Firstness) but rather aggregates in constellations of participation, that is, the color red is seen as part of a constellation of the reds in my life (a red dress, the robin’s breast, the Cardinal’s robes, the stop light, etc.),24 but he neglects to historicize this participation. As Sara Ahmed might say: he does not allow for differences of orientation.25

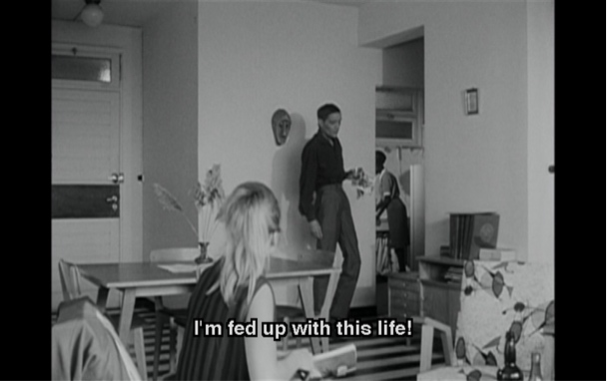

Do Diouana and the Woman see the same apartment? I have asserted (and will argue more fully below) that the presence of the mask demonstrates through film form that the two women do not share a world or perceptions of the world. Another way to assess the question is to consider the feelings the film opens up toward the white woman, the Woman. As a white feminist I know well the history of second wave feminism in criticizing the oppressions of (white) bourgeois marriage; nonetheless, the film enables very little feminist sympathy for this white woman’s alienation, even though one scene in particular suggests this alienation starkly: the scene in which the Woman berates her husband for drinking and not paying attention to her. The dynamic is exacerbated by the fact that when the husband gets up to take a nap—the action that propels his wife’s stream of angry words—he stops at the kitchen doorway and leans in to look at Diouana. In a reverse shot she glances up at him, but the camera returns quickly to Monsieur, and he seems to leer at her.

When the camera subsequently captures him in bed, a girlie magazine lies open beside him.26 The short sequence potentially reframes the Woman’s bitter impatience with Diouana as jealousy, perhaps even feeling that her marriage is in jeopardy. The reframing remains potential, however. It almost seems as if Sembène included the scene in order to stress the limitations of external perception, because viewers have only the Woman and Man’s external conduct to judge. The film provides no god-like access to their inner thoughts, no nuance to their character. Kept to the exterior and limited only to what we see, the Woman resembles the behemoth white ocean liner from the film’s opening shot, lumbering slowly through the space of the apartment, and Diouana darts about her like the small fishing boats, moving toward and then away, but cutting—at best—only a short, parallel line to her. The chiasm generated by their physical proximity does not yield what Merleau-Ponty terms a “connection” or a “common” world.27

The Mask as Transcendence

As the visible and objective disruption of the film’s relational chiasms, the mask is positioned to mark asymmetry. My suggestion above that the mask is the écart that shifts Euclidean space to phenomenological topological space is phrased in response to Merleau-Ponty’s differentiation of these two kinds of spaces. He writes, “Euclidean space is the model for perspectival being, it is a space without transcendence, positive, a network of straight lines, parallel among themselves or perpendicular according to the three dimensions, which sustains all the possible situations,” whereas, “topological space, on the contrary, [is] a milieu in which are circumscribed relations of proximity, of envelopment, etc.”28 To oppose non-transcendent, Euclidean space, topological space must include transcendence, and it does so, paradoxically, through relations such as proximity and envelopment. In Black Girl the mask enacts this sort of topological transcendence by marking divergence from the rational, geometric space of white dominance through its enveloping proximity. That is, the mask hangs proximate to the primary characters in eachcrucial scene, and yet can be seen to comment on the human interactions from a non-immanent perspective and set of values. Although the metaphor of ‘chiasm’ models a predictable mirror inversion, I am suggesting that the mask shows up the geometry of chiasm as always-already distorted by the unpredictable topologies of its various reflecting surfaces—bodies, social stratifications, and the material culture of things like furniture, room use, and cooking. The mask indicates how each relational chiasm, sketched out by the camera is also skewed by asymmetrical power relations.

About the objects and persons that fill our lives Merleau-Ponty writes, “There is an Einfühlung and a lateral relation with the things no less than with the other [human]; to be sure the things are not interlocutors […]. Like madmen or animals they are quasi-companions.”29 Merleau-Ponty sketches the contours of a world affective, material, and bodily—through the primary geometry of rational and embodied connection. He asserts clarity of symmetry that veils a dynamic of mastery and control (for who is to say that madmen or animals would accept our denomination of them as quasi-companions?). Sembène’s placement of the mask, however, demonstrates that Diouana and her white employers share no Einfühlung, not through the apartment she cleans, and not through the food she cooks, and not even through Diouana’s very gift of the mask to les Blancs in a naïve assertion of the empathy she desires and expects. Though les Blancs treat Diouana as a thing, a madwoman, and an animal, Diouana is not even a quasi-companion to them. She is, like the mask on the wall, only an object possessed. She is an unseen and unsaid site of transcendence (more on this in a moment).

Merleau-Ponty’s phenomenology does at times attend to modalities of unhappiness, of neglect and abuse and abnormality, but his accounts of experience and film allow no way to underscore and theorize how unhappiness for some is alwayswoven into the presumptions of the so-called world as it is. Sembène, on the other hand, and more congruent with poststructural and object-oriented theories, conveys oppression succinctly by positioning the mask as the interruption of the film’s relationships, and, arguably, the physical manifestation of Diouana’s interior monologue.30 The voice-over is a tool for expressing the difference between what we see and what we hear. It demonstrates for us the resistance of Diouana’s self to what the object of her body experiences, and the mask’s mise en scène underscores the disruption of those relational chiasms.

Diouana is herself a kind of mask, and viewers are positioned, through the mask of the camera, as a kind of god-like observer of her story. These two maskings are pulled together by the religious presence of mask-as-object. It sits within the film in the same position as we viewers sit outside of it—god-like, transcendent, and able to assess and comment on the action. The mask and Diouana are both veiled before the whites, and both rendered as things by them, valued for their “authenticity” but only as an object that can be possessed on the wall or in the kitchen. The transcendent religiosity of the mask is as foreclosed to the whites as is Diouana’s humanity and unique subjectivity. In fact, the religious character of the mask is situated precisely in its ability vaguely to hold out the identities, values and norms that are at play in Diouana’s internal monologues. It is the affective crucibleof ethical critique and the religious charge to live differently. The mask functions religiously to remindviewers to feel the excess of Diouana’s world over the white couple’s perception of it, to emphasize the disjunctionof her world from theirs, and to hold out hope for a world that generates and insists on ethical acts and dispositions that will acknowledge and attenuate the “differential of distributions of precarity” that are the lived consequences of disjunction. 31

“That being is transcendent means precisely: it is appearance crystallizing, it is full and empty, it is Gestalt with horizon, it is duplicity of planes, it is, itself, Verborgenheit [concealment]—it is it that perceives itself, as it is it that speaks in me.”32 Here Merleau-Ponty’s description of transcendence perfectly fits the mask’s function in Black Girl (though his phenomenology remains less apt!). The mask is full and empty, redolent of Senegal’s national hopes and values and of Diouana’s personal hopes and desires, and yet not representing any of these affects so much as presenting them as empty form. It is Gestalt, and yet always diverging from its ‘place’ on the white wall, aiming at the horizon of Senegal (and not even the actual Senegal, but rather the projected Senegal of decolonial theory), and as such it is a divergence of planes, fully part of the Euclidean geometry of white, commodified rationality, but also transcending it by signaling another topological grid of thought, feeling, and being.

I can now track a few ‘appearances’ of the mask in the film in hopes that attention to its placement will shed light on Diouana’s suicide, an act that takes aback my (mostly white and not impoverished) students. The filmic moment that particularly baffles them is this: after finally receiving twenty thousand francs from the Man, why does Diouana fight over the mask with the Woman and then slash her own throat? Why not just leave? Go home? Or at least go shopping?

Reading the Film

I. Set-up

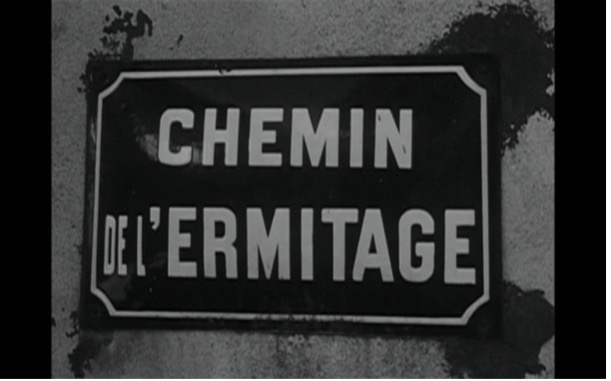

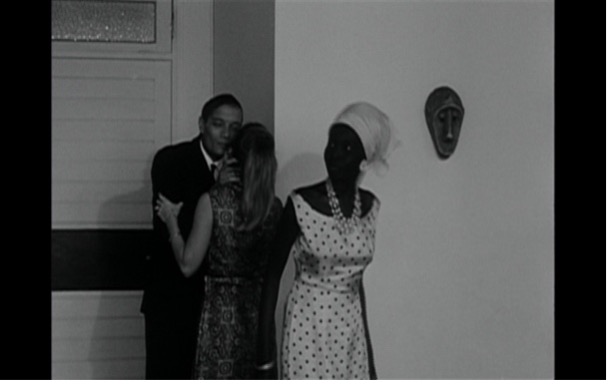

After the white Manmeets Diouana’s ship he escorts her to his car and drives her to his apartment. When they have nearly arrived, the camera cuts to a street sign, “Hermitage Path,” a name that suggests the religious isolation sought by monks, nuns, or ascetics. The shot does not ‘belong’ to any particular character; it is not shown as a point-of-view shot from the car. Instead, the unmotivated shot anticipates Diouana’s physical enclosure in the white couple’s apartment, an enclosure that is as sure and disciplined as that of a religious hermitage. But the image also evokes the possibility that something like religious meditation or spiritual growth might occur. The faithful enter a hermitage in order to wrestle through something, to dedicate themselves to a specific spiritual discipline, or to attempt to grow in faith or love or virtue. At this moment in the film, it hardly matters that Diouana is not a nun but a maid, that she did not choose enclosure, and that she does not set any task for herself more spiritual than to see the loveliness of France and consume its lingerie, dresses, jewelry and beaches. Indeed, I would argue that the disjunction between the vague promises suggested by the road sign and Diouana’s own vague hopes is the point of this utterly unnecessary shot: it stands transcendent to her situation, and omniscient about it. Importantly, the structure of this cut-away to the road sign is repeated in a similarly unmotivated cut to the mask, directly after Diouana enters the apartment. When Diouana and the white Man finally enter the apartment, Diouana moves into its open space while the couple embraces just behind her, with the mask hanging on the wall in line with Diouana and to the side of the couple.

Then the camera cuts in to a close-up of the mask. If the road sign had led to a Christian hermitage, and the camera had cut to a crucifix at this point, the message would be equally clear: the mask inheres the values that shape Diouana and stands as normative witness of the room’s inhabitants.

II. Bodily Alienations

When Diouana begins her work in the apartment, she is still attired in the polka-dotted dress, heels, and beaded jewelry the white Woman gave her in Dakar. In one telling scene the white Woman berates Diouana for dressing up and insists she wear an apron. The exchange is short, but the mask hovering behind them frames and magnifies it. On the one hand, the Womanhas simply delivered a trivial directive to her maid; on the other hand, the insistence on the apron marksthis fashionable African woman as servant and renders her a controlled object within a narrowly circumscribed role. In the next sequence, when Diouana serves an ‘authentic’ Senegalese meal called ‘mafé’ to a lunch party, the mask is positioned directly opposite the white Woman; but when a white male guest asks the white Man permission to kiss Diouana (because he has “never kissed an African”), the mask shifts in line with him. This subtle re-framing enables the mask to destabilize the ‘obviousness’ or ‘naturalness’ of the racially charged servant-employer relationship. As with the apron scene, the kiss scene is both trivial and momentous. It is only a small peck, a laugh among the white men. And yet it also is a singularly total appropriation of Diouana’s body and agency. Directly after the kiss, the white Woman comes into the kitchen to tell Diouana not to be offended, a defensive action that confirms the kiss as assault. At this point, the film melts into its first flashback (see below). When the flashback ends, viewers see again the mask hanging on the bare wall of the French apartment as Diouana comes in to clear the table of ‘mafé’ and wine.

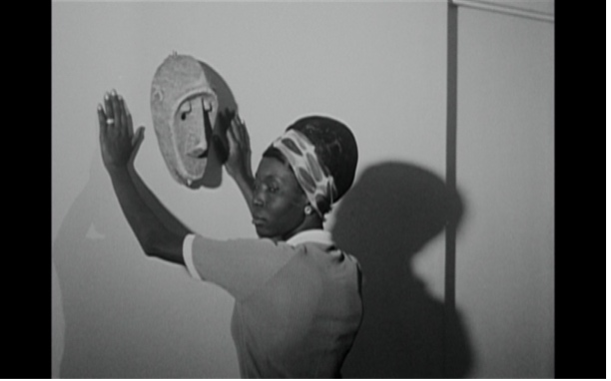

A third short scene is pertinent for considering the film’s bodily alienations. Almost exactly at the film’s midpoint, Diouana is shown standing directly in front of the mask, bringing her face close to it and stretching her arms out on the wall next to it.

In this languid, erotic pose, viewers hear her internal voice imagine the people in Dakar, jealous of her ‘life’ in France. But, really, she asks herself, what kind of life is this? She stands poised between the mask and her own shadow, and as she walks off-screen and back to her domestic tasks, the camera lingers on the mask. The scene is haunting for its oozing sensuality and sadness. Not even in bed with her Senegalese boyfriend (during the second flashback) do viewers see Diouana express her desires so clearly and so bodily. Her interior monologue remains cold and logical: “The children are off at school; I clean the same four rooms; I cook the meals.” And yet her body sidles up to the mask and looks up at it in visceral longing. Does she long for home? I think rather she longs for the Senegal—and the Senegalese citizen-subject—evoked by or in the mask; that is, she longs for the not-yet-material hopes of a decolonized Senegal, for a world where Diouana’s life “will have been worth” the jealousy of contemporary Senegalese bodies. The more acutely she lives the callous invisibility wrought by her disjunctions from the world of les Blancs, the more the mask comes to embody her hopes for acknowledgment and attenuation of those disjunctions. At this moment, however, Diouana still does not have a sense of what ethical acts and dispositions would address her hopes.

As each of these images of bodily alienation demonstrates, the camera of Black Girl again and again catches Euclidean lines running between les Blancs and Diouana. The camera frames human relationships in squares and triangles, in lines that seem at once definite and natural; and each time, the mask disturbs the flat, commodified rationality of those lines with topological transcendence. The mask underscores the formal relationships caught by the camera and questions their equanimity and naturalness. What began as an empty structural relationship—like the road sign that anticipates a destination without definite content—becomes through the rhythms of the film, the topological transcendence of proximity and envelopment.

III. Flashbacks

(A) The first flashback revolves almost completely around the mask, beginning with a blurry dissolve from Diouana to her brother wearing the mask. Viewers hear a voice (the father) saying, “take it off” and a young boy comes into focus. This transition-shot powerfully exemplifies the transcendent access given to viewers by the film’s camera consciousness, since even though this scene is part of Diouana’s flashback, she is still inside her father’s house at this point and could not possibly witness what is happening with the boy. Later in the flashback, after Diouana finally secures a job with les Blancs, she returns home and playfully lifts the mask from the boy’s lap. He chases after her, but Diouana puts the mask on her face and circles round and round chanting, “I have work! I have work with the whites!” As Diouana sits down, viewers hear her relate that her mother “threw down the mask and told me to be brave.” The boy again picks up the mask, but Diouana stops him with her offer to pay him 50 francs for it. Diouana carries the mask to her employers’ house and give it to the white Woman. Les Blancs examine the mask as if they were considering a purchase, finally deem it “authentic” and look around for a place to display it. Since their walls are full of displays of other masks, they prop it up on a bookcase next to a small statue.

That so much of this first flashback concerns the mask reveals its centrality to the political and rhetorical work of the film. Both the father and mother tell the children to remove the mask. It is not a toy, not an object of play or fancy. As a religious object—as an object that inheres transcendent values—it carries social rules and expectations about its use, including prohibitions that protect its sacredness. If it is fraught to wear the mask, it must be worse to sell it out of the community. The stretched time, languid movements, and full-shots that structure the scene in which the white couple contemplates where to display their new, “authentic” fetish indicate the error of the gift transaction. Diouana’s abetting the mask’s commodification suggests her naivety and provides a reason why she might require the self-reflection or meditation anticipated by the Chemin de L’Ermitage road sign. Diouana is engulfed in the exchange relationship but naively thinks she—her self, her worth as a human being—can be separated from the reifications of labor, gender, and colonial exchange. She thinks she can put on and take off the decolonial hopes of Senegal, and she even assumes that les Blancs are allies in these hopes. The “hermitage” of the whites’s apartment in Antibes will teach her differently; the ‘liberation’ of exchange value will be shown to be a dead end.33

(B) The second flashback occurs just after Diouana asserts herself by taking the mask off the white couple’s wall, and it is as absent of the mask as the first is centered on it. Once again Sembène signals the flashback with a blurred image, this time of the street sign “Independence Place.” Like “Hermitage Path,” the sign frames Diouana’s situation. Instead of anticipating her (unwilling) retreat into the ascetic cell of the French apartment, “Independence Place” frames a public square, a site at once personal and political. Since Diouana has employment and an attentive boyfriend in Senegal, she might feel the right to a lived sense of citizen independence. But in fact, she is not a citizen in the way that men are citizens, and she is objectified—owned and claimed—by her boyfriend as much as by her employers. What ought to be the lineaments of autonomy are actually the chains that bind her to submission. Walking out with her boyfriend, Diouana takes off her ultra-feminine high-heels and climbs up and around a memorial to the Senegalese (men) who died in WWII. Seeing officials approaching the memorial, the boyfriend scolds Diouana sharply for showing disrespect. He even calls her action “sacrilege.” But the memorial is not guarded or gated; her feet can hardly be the first ones to tread its enticing slopes and angles. Is the fury of the boyfriend fueled perhaps by the vague sense that Diouana here removes a marker of femininity and tactilely claims equality with the men whose deaths inspired Senegal’s “independence” from France?34

This second flashback is decisive for indicating that the Euclidean space of Senegal is no more life giving to Diouana than that of France. Devastating to watch, the sequence interrupts the desperation Diouana feels at her entrapment in France with a different but no less dire entrapment in Senegal. Since the mask, which signals the film’s transcendent symbol of hope and possibility, is literally torn from the wall just prior to this flashback and is crucially absent within it, we can view this flashback as drawing the algorithm of decolonial desperation with acute starkness. It shows the complete diremption of Diouana’s life between two impossibilities, that of economic ‘independence’ in France and that of personal ‘independence’ in Senegal. When the flashback ends and the camera returns to Antibes, it pans up Diouana’s body, down to the photos of herself and her boyfriend, and over to her shoes before stopping back at her feet. The circular caress of the camera renders Diouana whole through the mediation of the mask… and the audience has now become the transcendent witness.

IV. Death

Diouana and the white Woman fight over mask, turning round and round like a whirligig. Cinematically the moment is brutal and unique because unlike any other shot in the film, here the camera, mise en scène and actors together explode the film’s geometric calm with a literal spinning of emotion. It is a scant few seconds of affective release—of chaos and struggle—lodged in a film notable for its exquisitely quiet geometries and passive plot. When the camera returns to the predominant Euclidean precision of the film, Diouana returns the money the Man finally gave her, packs up her suitcase and retires to the bathroom dressed in her white robe. The camera cuts immediately to an overhead shot of her dead and bloody body lying nearly naked in a full bathtub, the bloody razor on the floor. Death is incredibly quiet here, devoid of the typical filmic anticipations, drama, and horror.

Following Diouana’s suicide, the brief beachside interlude reframes Diouana’s horrible struggle as an unhappy but insignificant event within post-colonial French society. Instead of full-screen road signs, her death is announced by a tiny square of a local newspaper. A few seconds flit by and the camera cuts to a full screen, overhead shot of the mask. Viewers watch the white Man decide impulsively to travel to Dakar in order to return the mask to Diouana’s family. At the family home, the brother stares intensely at the mask and Diouana’s mother refuses the salary money. When the white Man leaves, the boy holds the mask over his face and follows him like a ghost stalking a criminal. The film ends with viewers looking at a full-screen, head-on shot of the boy wearing the mask, which lowers slowly to reveal the boy’s bemused face.

Conclusion

The mask fills the screen throughout Black Girl, and its significance is as vague as it is obvious and multivalent. The stakes of its vague valuations are more evident when the mask is correlated with Diouana and les Blancs as simultaneously singular and collective entities—individual persons and also national types. To see les Blancs as somehow (also) ‘France’ and to consider Diouana as somehow (also) ‘Senegal’ renders easier the task of drawing out the operations and meanings of the mask as a religious object, and of understanding why Diouana ends her life (instead of taking her salary and walking away). Again, to recite Bill Brown, “objects mediate our sense of ourselves (as individuals and as collectivities) and our sense of others.”35 I have argued that this film’s particular object, the mask, mediates a religious sense of person and nation in its reminderof the excess of the world to any one perception of the world, and in its exhortation to resist colonial exploitation of labor, decolonial exploitation of women, and the death-dealing indifference of racism.

Diouana should never have bought the mask from her brother and never have gifted it to the white Woman because it was a ritual object of national-cultural significance, a fact conveyed by the parental warnings spoken of it (“Take that off”; “she threw down the mask and told me to be brave”). The double mistake belies Diouana’s double naivety, since both as a young woman selling her labor on the market, and as a body standing in for the cultures and traditions of Senegal, her actions make relational claims that the reductions of value and life to the labor economy foreclose. Diouana’s gift is a human gesture; it exceeds her social position as maid or nanny. But the excess of her human subjectivity to the reifications of her labor remains imperceptible to the French couple—as is the acceptance of Senegal as something more than a source of labor or natural resources. By positioning the mask as transcendent to the diegetic actions of the film, the filmic geometry is interrupted, and the mask reminds viewers of the excess of life to labor, and human value to exchange value.

As a religious object that inheres and externalizes the values and vague hopes of Diouana and Senegal (or Diouana as Senegal), the mask claims a status and connection beyond human social exchange. The film demonstrates this claim through a filmic geometry of transcendence that transmutes the cold, Euclidean geometry of white, European dominance into a fraught topography of racialized struggle and gendered despair. Diouana completes the ascetic work of the hermitage when she takes the mask off the wall, signaling that she ‘knows’ or senses her mistake in making it a gift—and finally feeling how any gift between herself and her white employers will always fail to bridge the disjunctions between France and Senegal. Through the ascesis of the hermitage—made palpable through the mediations of the mask—Diouana realizes she cannot stay in France and she cannot go home. The disjunctions of her world from the French-white world—and the disjunction of her female body and desires from the male bodies and desires of Senegal—are too intractable. Diouana’s suicide acknowledges and refuses the contradictions of exchange value and the contradictions of socio-political agency that are written into the shape and color of her body.36

Is she a sacrifice for Senegal, then? Or a sacrifice of Senegal? I suggest that in taking back the mask from her white employers, Diouana materially reclaims the (vague) religious hopes for a just and compassionate Senegal. In giving up her own life she subsumes the values and hopes of her life into the object of the mask and also throws down a material challenge to the Senegalese boys primed to take up the reins of national and cultural power.37 When her brother places the mask over his face, we imagine the ghost of Diouana haunting her former employer because we ‘see’ through that mask the events that she endured, and we see the brother symbolically take up the disruptive judgments of the mask as well as his sister’s resistance and hopes. The final image of the boy and the mask positions the audience as the white man and triangulates us with the mask and the male youth of Senegal. The boy stares at us—at white Europe—and it is now as if we become the hermitage inhabitant, the one being addressed by the eye of the mask. From this last image we might concede that Diouana’s death asserts Merleau-Ponty’s point: we dolive in the same world. But the phenomenologist misses what the poststructuralists emphasize: that the factors obscuring and or minimizing the commonality of the world are equivalent to murder—and that murder, the murder of life and soul, forms its own chiasm with Diouana’s suicide. Death or death—that was her choice. And in the face of that non-choice the religious object of the mask stands as the necessary interruption, inhering values that buck against economic exploitation and exhorting men of all races to strive not only for the humanity of humans, but for the particular humanity of women.

M. Gail Hamner

- Polly Savage, “Playing to the Gallery: Masks, Masquerade, and Museums,” African Arts 41 (2008): 74. ↩︎

- Bill Brown, “Objects, Others and Us: The Refabrication of Things,” Critical Inquiry 36, no. 2 (2010): 186. The full citation is as follows: “I’m interested in how particular objects dramatize the problematics of otherness, which is to say the uncertainties that inhere in any identification of sameness or difference be it argued or experienced or acted out.” ↩︎

- For an expanded discussion of transcendence in film, see M. Gail Hamner, “Introduction,” in Imaging Religion in Film: The Politics of Nostalgia (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011). ↩︎

- Brown, “Objects, Others and Us,” 187. ↩︎

- In this paragraph the information with dates is from Françoise Pfaff, The Cinema of Ousmane Sembène: A Pioner of African film (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1984), 183-84. Pfafff’s book is also a wonderful resource generally for biographical information on Sembène, in addition to Samba Gadjigo, Ousmane Sembène: the making of a militant artist, trans. Moustapha Diop (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2010); David Murphy, Sembène: Imagining Alternatives in Film & Fiction (Oxford: James Curry Press, 2001); and Paulin Soumanou Vieyra, Ousmane Sembène cinéaste: premiére période, 1962-1971 (Paris: Editions Présence Africaine, 1972). ↩︎

- See “Form and Temporality in Ousmane Sembène’s Xala,” in Eli Park Sorenson, Postcolonial Studies and the Literary: Theory, Interpretation and the Novel (New York: Palgrave, 2010), 75-95. The novel, Xala, was later made into a film by Sembène himself in 1975. ↩︎

- Vieyra notes that Sembène was preoccupied with questions of what makes an “African” film, what makes a “Senegalese” film, what language(s) should be central in film (French or Wolof), and how to secure the distribution of films to their African audiences. See Vieyra, Ousmane Sembène cinéaste, 23-24. ↩︎

- See Charles Gore, “Masks and Modernities,” African Arts 41 (2008): 4. Gore notes that “Senghor’s project of École de Dakar from 1960 drew on the ideas of Negritude, where a generalized iconography of mask was prominent in presenting a modernism based on the assertion of a common Pan-African heritage. This was rejected by a following generation of Senegalese artists.” ↩︎

- C. S. Peirce, “Vague,” in Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J.M. Baldwin (New York: MacMillan, 1902), 748: “A proposition is vague when there are possible states of things concerning which it is intrinsically uncertain whether, had they been contemplated by the speaker, he would have regarded them as excluded or allowed by the proposition. By intrinsically uncertain we mean not uncertain in consequence of any ignorance of the interpreter, but because the speaker’s habits of language were indeterminate.” ↩︎

- Brown, “Objects, Others and Us,” 187. ↩︎

- “Exclusion appears as the final and decisive element by which a social space completes its formation and closure on itself. […] It is not because the social space was formed and closed on itself that the criminal was excluded from it; but the possible exclusion of individuals is one of the elements of the formation of the social space.” Michel Foucault, Lectures on the Will to Know: Lectures at the Collège de France 1970-1971, ed. Deaniel Defert; gen. ed. François Ewald and Alessandro Fontana, English series ed. Arnold I. Davidson, trans. Graham Burchell (New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2013), 180. ↩︎

- Sembène ends the film on this image, which has led many film commentators to compare it to the famous last image of François Truffaut’s The 400 Blows (Les quatre cents coups, 1959). I find it significant, however, that the image is not a freeze-frame; it conveys the same sense of impasse because of the chain-link fence behind both boys, but Sembène indicates his optimism for the future of Senegal by keeping the camera rolling. ↩︎

- The sense of quiet stems in part from the fact that Diouana’s voice is rendered mostly in voice-over as an internal monologue, and in part from the fact that the meager dialogue of the white couple cannot by itself constitute the film’s tragedy. The soundtrack paradoxically adds to the film’s silence since its nearly constant music, which functions to mark the different locations of France and Senegal. Since the music is always non-diegetic its presence oddly underscores the empty silence of the apartment. ↩︎

- Gilles Deleuze uses this term, “camera consciousness” to indicate the freeing of visuality from action-oriented plot in many post-WWII films. According to Deleuze, the camera in these films does sometimes track a character’s POV (point of view), but more often it caresses landscapes and situations from an ambivalent perspective that does not align neatly with director, protagonist, or a transcendent (“omnipotent”) narrator. See Deleuze, Cinema 2: The Time Image, trans. Hugh Tomlinson and Robert Galeta (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1989), 23. ↩︎

- My translation of L’Institut des hautes études cinématographiques or IDHEC. Pierre Rodrigo notes that this essay is reprinted in Sense and Non-Sense, and that its argument about cinema differs from that in the Collège de France lecture notes entitled Le monde sensible et le monde de l’expression. Rodrigo also notes a late reference to cinema in the last chapter of Eye and Mind, which queries how cinema shows movement and rejects a Cartesian explanation (i.e., cinema breaks movements down into their component parts so that we can ‘see’ them better). ↩︎

- Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Le cinéma et la nouvelle psychologie (Dossier par Pierre Parlant; Lecture d’image par Arno Bertina) (Paris: Éditions Gallimard, 2009), 5-24. ↩︎

- Emphasis added. The original French is as follows: “Cette psychologie et les philosophies contemporaines ont pour commun caractère de nous présenter, non pas, comme les philosophies classiques, l’esprit et le monde, chaque conscience et les autres, mais la conscience jetée dans le monde, soumise au regard des autres et apprenant d’eux ce qu’elle est. … Or, le cinéma est particulièrement apte à faire paraître l’union de l’esprit et du corps, de l’esprit et du monde et l’expression de l’un dans l’autre.” Ibid., 23. ↩︎

- “Pour le cinéma comme pour la psychologie moderne, le vertige, le plaisir, la douleur, l’amour, la haine sont des conduits.” Ibid., 23. ↩︎

- “Expression” was the subject of Merleau-Ponty’s first (1953) lectures at the Collège de France. See Merleau-Ponty, Le monde sensible et le monde de l’expression, ed. and annotated by Emmanuel de Saint Aubert (Geneva: Metis Press, 2011). In these still-untranslated lectures ‘expression’ refers to the cultural engagement and understanding of things (“les choses culturelles, les ‘objets d’usage’, les symboles,” 45) and he states his goal as “approfondir l’analyse du monde perçu en montrant qu’il suppose déjà la fonction expressive.” ↩︎

- Sara Ahmed, The Promise of Happiness (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2010), 6 (emphasis added). ↩︎

- Jacques Rancière, Dissensus: On Politics and Aesthetics, trans. Steven Corcoran (New York: Continuum, 2010), 12. ↩︎

- Merleau-Ponty, The Visible and the Invisible, trans. Alfonso Lingis (Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 1968), 142. ↩︎

- Sembène did film 10 minutes of colored footage that captured the bright tones of the French Riviera during the car-trip from the ship to the apartment. It was omitted due to financial and technical difficulties but would have added to this conversation. The colors of France signify differently for Diouana than for her white employer. See, Jonathan Rosenbaum, “Black-And-White World [Black Girl],” Jonathan Rosenbaum, September 22, 2023, org. April 21, 1995, https://jonathanrosenbaum.net/2023/09/black-and-white-world/. ↩︎

- Merleau-Ponty, The Visible and the Invisible, 132. ↩︎

- Sara Ahmed, Queer Phenomenology: Orientations, Objects, Others (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2006), 1-5. ↩︎

- My thanks to Dai Newman for catching this detail. ↩︎

- “The other is no longer so much a freedom seen from without as destiny and fatality, a rival subject for a subject, but he is caught up in a circuit that connects him to the world, as we ourselves are, and consequently also in a circuit that connects him to us—And this world is common to us, is intermundane space….” Merleau-Ponty, The Visible and the Invisible, 269. ↩︎

- Ibid., 210 (underlining added). ↩︎

- Ibid., 180. ↩︎

- The voice-over is spoken by a different actress’s voice, and it is an older and more sophisticated voice than that of the rather simple girl viewers see on screen and who responds to her employers with flat “oui, Madame” or “non, Monsieur.” See the discussion of this aspect of the film by Prof. Charles Sugnet, Walker Art Center, “Introduction and Post-Screening Q&A for the Film Screening of Black Girl,” YouTube Video, 29:30, November 5, 2010, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VCoD7FDPbgY. The irony, of course, is that Diouana is perceived by les Blancs as not being able to speak French, whereas her internal monologue proceeds in a mellifluous and fluent French. Some scholars see this contradiction as structural, an unfortunate effect of this French-produced film that Sembène ‘corrects’ in his later films, when he employs Wolof-speaking actors and French subtitles. I do not disagree, but it also is possible to ‘hear’ Diouana’s simultaneous ignorance and mastery of French as another example of how colonial racism renders her invisible and unsayable, even while she is directly, bodily, there. ↩︎

- For a discussion of precarity in this sense, see Judith Butler, “Introduction,” in Frames of War: When is Life Grievable? (New York: Verso, 2010), 2-3. ↩︎

- Merleau-Ponty, The Visible and the Invisible, 76. ↩︎

- In Vieyra, Ousmane Sembène cinéaste, the authors underscores that the unhappiness between Diouana and her white employers only begins in France. While in Dakar, the three remain amicable and peaceful. The white Woman gives Diouana dresses and shoes and therefore does not seem to show up Diouana’s gift of the mask as a mistake. Vierya calls Diouana’s gift “une marquee de confiance et d’attention” to her “patronne” (59). In line with my comments about exchange value, Vierya explains the change in Antibes in terms of class. He suggests that Madame can afford to be generous and polite in Dakar, but not in Antibes, where her domicile is smaller, she can’t afford a cook, and life is less abundant. Vieyra reads the film as a critique of the former colonial intellectual bourgeoisie (67), and suggests that Antibes shows this class in a “moment de crise” (68). ↩︎

- Prof. Charles Sugnet discusses this. See Walker Art Center, “Introduction and Post-Screening Q&A for the Film Screening of Black Girl,” 20:00. ↩︎

- Brown, “Objects, Others and Us,” 187. ↩︎

- The white couple did accept Diouana as sheer exchange value, even in Dakar when the relation was not bitter. The white Woman dictates (1) to the cook in Dakar: “If she breaks something, she pays for it”; (2) to Diouana in Antibes: “I bought you this” (apron, sign of your servitude); (3) to Diouana: “Don’t forget you’re a maid”; (4) to her husband: “How ungrateful she is; after all I’ve done for her!” Even more than the white Man, the white Woman expects Diouana to show happy submission simply because she is employed. Diouana, on the other hand, accepts the labor and conditions of contract, but also expects human exchange. This interpersonal labor relation can easily stand in for the much more complex colonial relationship between France and Senegal. ↩︎

- This is somewhat like the extreme view the father and title character expresses about his daughter’s prostitution in Sembène’s 1992 film, Guelwaar. ↩︎