“More than 500 plant species have disappeared from Earth in recent history. Never will we know them. More than half of sound films made on film material have been lost and more than 90% of silent films, too”. From this comparative diagnosis between two forms of material memory, the film Herbaria (Argentina/Germany, 2022) by filmmaker Leandro Listorti explores the politics of the preservation of natural and artistic heritage. His documentary film enquires about the issue of extinction in the context of the current ecological and environmental crisis. From this aesthetic artifact as a trigger, I would like to critically approach the role played by modern classificatory enterprise and its criteria of knowledge and collecting in the fields of science and art from a materialist and postnaturalist perspective.

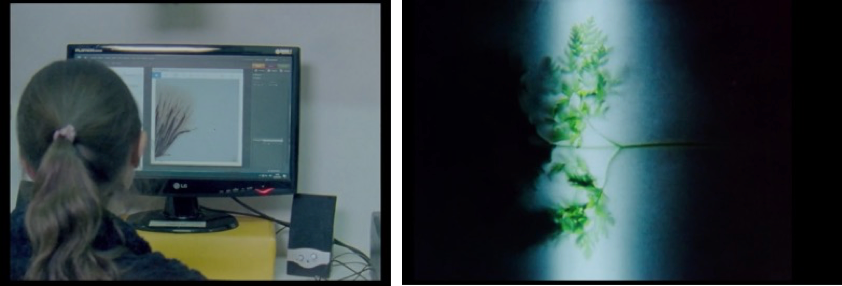

Relationships between films and plants go back to the beginning of cinema itself. Many of the experiments developed during the 19th century, in photography and moving images, highlight the agency of both the cinematographic and the vegetal in the creation of forms and worlds, showing the entanglement of nature and technology (Lopes Coelho, 2023, p. 35). Though always present, the demands of the climate crisis and the arrival of digital media expedited the revelation of these relationships. Reflecting on the materialities constituting the archived media, such as their vulnerability to time and the action of biological agents, Listorti’s work proposes a sensorial invitation to engage with these artificial yet very organic archives, both confronted in similar ways by an era of loss and ecological degradation. Using materialist film procedures (experimentation with emulsions, alternative techniques, and analogue machines), Listorti forms part of the new film ecologies which are currently developing forms of experimental film, expanding the potentialities in relation to the progressive extinction of nature (Wiedemann, 2020; Della Noce and Murari, 2022). As Salomé Lopes Coelho points out regarding the entanglements between cinema and plant worlds in contemporary Latin American cinema, “the background of the plant worlds in relation to humans is not only the choice of what to depict but also how to depict it through different cinematic techniques” (2023). In this sense, Lisorti’s proposal goes beyond a naturalist paradigm, challenging human exceptionalism.

One of the main challenges presented by the current environmental crisis is the impossibility of teaching or conceiving it. Because it is not about an observable fact or phenomenon, but about a series of effects, considered adverse, of a great number of processes involving different climate variables, also related to a mesh of economic, social, and political factors with a high impact on the biosphere. There is difficulty in understanding this global and multifocal phenomenon; nonetheless, the fact that it is complex doesn’t mean that it isn’t sensitive, perceptible, or registrable. When we analyze it from an aesthetic perspective, the overview becomes paradoxical: the environmental crisis cannot be conceived, but it can be represented. We live in a world composed of media existences and images made by machines that shape a continuum with life. In contrast to the human eye, which perceives, the machine’s eye, which is nonhuman, registers. The inability to register the environmental crisis—although we cannot think about it—is what leads me to introduce Silvia Schwarzböck’s ideas about the aesthetics of explicitness (2022). This author proposes that contemporary images, insofar as they become infinite, are archived in nonhuman memories, erasable and resettable. This change in the status of the eye demands of aesthetics (and of the whole of philosophy as a discipline) a materialist turn: from a human to a posthuman eye. As for the climate crisis: this allows itself to be seen, it doesn’t hide, and this non-concealment, its explicitness, is what makes it disturbing. The proliferation of images related to the environmental crisis is part of the crisis itself. Hence, what effects do these images, caught by nonhuman apparatuses, generate at the crossroads of different ways of seeing? By means of artistic research, Listorti’s film draws attention to those devices where the audiovisual and vegetable sensoria are entangled. What I want to point out in the film Herbaria is the aesthetics that certain vegetable and technical bodies (and nature is always technical) deploy in the frameworks they contribute to building. An experience of the explicitness of the potential incompatibility of the modern world with the life of most of its species. In Herbaria the technical-vegetable sensorium is, thus, the main vector of the explicitness of the ecological emergency.1

Listorti’s film invites the viewers into two intertwined archives: the botanical archive and the analogue film archive. Who decides what to keep and what to dispose of? How and in what context is the editing work in archives done? Of course, answers in this field aren’t easy given that they involve ways of knowledge construction, heritage decisions, and archive practices, crossed by specific policies in each case. However, we can inquire into the ecology of practices that herbaria and films deploy as epistemological devices in memory preservation of those that deserve to be stored. I sustain that, as artefacts that encompass the human and the non-human, these devices are processual modes of existence with complex overlaps between experience, perception, and subjectivity. In the context of scientific and artistic practices, ecology is understood here as a set of forms of commitment and entanglement that connect entities of a socio-technical-material diversity. I deploy Erich Hörl’s concept of “general ecology”, which pluralizes and disseminates the modern concept of ecology, beyond nature, in non-natural ecologies; that even mutates into technoecology. The “de-naturalization” of the concept of ecology allows us to consider the ecological field as a framework from which to understand the imaginary production linked to systemic environmental concerns, offering a way to politicize it epistemically and ontologically (Hörl, 2017).

With the planetary scale of the current environmental crisis, an eco-political approach, as Listorti proposes in Herbaria, allows us to apprehend the ontological refoundation which urges or restores nonhumans as animated agents with sensitivity and language.

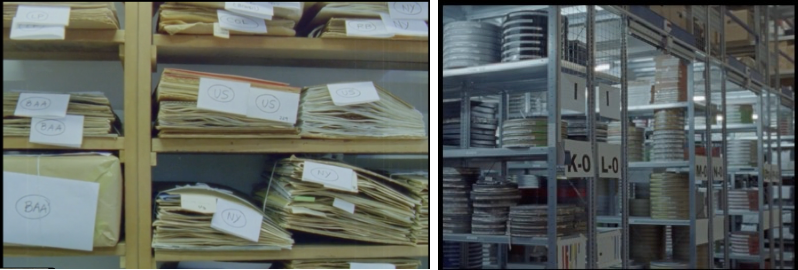

Given the methods of ordering, classification, and observation, botanical herbaria and film repositories share the organizing principle of the archive. In its etymology, the term arkhé brings together two beginnings: the place of origin where things of Nature and of History weren’t separated and the place where an order and authority were instituted and conserved (Derrida, 1995). This order, over time, acquired a sequential, topological, nomological and hierarchical form in the fields of natural sciences and in the arts as well. During the nineteenth century, with the consolidation of national states, the archival discipline was developing a logic of ordering to give consistency and organicity to the set of documents, objects, and specimens considered worthy of conservation; an operation that requires an outside, the backdrop to which the issues that matter are hierarchically defined. What I want to point out here is the ambiguity behind the modern archiving dynamics: on the one hand, it is the intangible reservoir where cultural and natural productions are preserved in an ideal sense; on the other, this immateriality of what is conserved is underpinned by the materiality that composes the archive; these are the mineral, animal, vegetable supports that sustain, resist, and fragment the inert material base on which what has relevance is recorded.2

Listorti’s film works on this ambiguity, highlighting the story and the drift of certain film and botanical archives on a horizon of temporal and spatial intersections: between America and Europe, between The Museum of Natural Sciences Bernardino Rivadavia and the Pablo Ducrós Hicken Film Museum, in Buenos Aires, Argentina on the one hand, and the Botanischen Garten and the Botanischen Museum, and the Deutsche Kinemathek in Berlin, Germany, on the other. As the documentary progresses, Listorti makes an increasing number of links between them. The ephemerality of celluloid is easily connected to the changes in wildlife, both those stemming from nature’s seasonal cycles and those affected by humans. In Herbaria’s storytelling, the emphasis is on the factors that intervene in the conformation of the botanical and film archives nowadays: first, the importance of biodiversity, the advance of the agricultural frontiers, and climate change; secondly, the restitution of analogue film practices, threatened by the empire of the digital. By means of a series of counterpoints, the film focuses on the procedures of conservation and representation in each field.

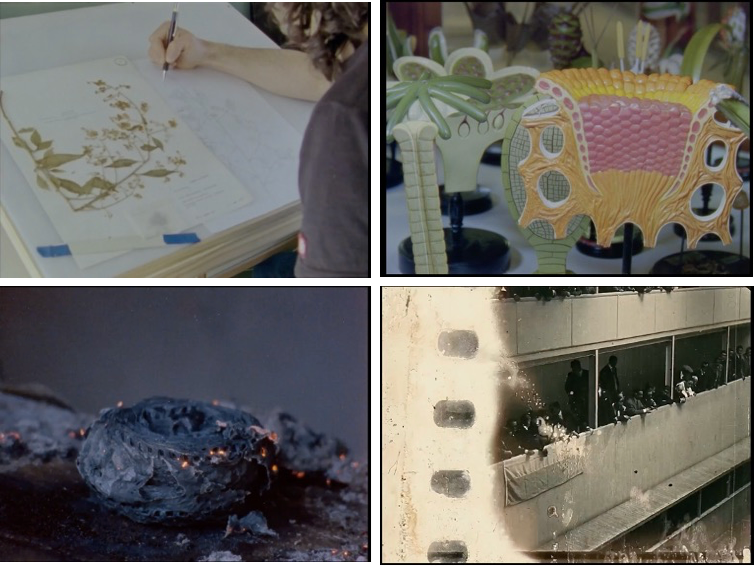

Thus, for instance, in botany the classic technique of illustration is described, that takes as a point of departure the herborized plant that lost its original shape and of which an iconic scheme is reconstructed in order to understand some basic features of the species. Also, the way in which the Brendel models were constructed is explained; these large-scale figures, made in paper mâché, wood accessories, glass beads, and feathers show what the plants look like inside. Nowadays, these devices are restored and exhibited as artistic work with aesthetic value. In the case of films, images are interleaved, coming from ancient unidentifiable and deteriorated films, which were scanned and whose digitalization implied, significantly, the whole destruction of the film material.

What is interesting from Listorti’s point of view is the problematization of the archive as a memory device and as a sensorium beyond the human. In this sense, his aesthetic proposal is part of contemporary debates about posthuman materialism that has allowed a new direction in speculative thinking, moving the focus from anthropocentric perspectives to an alternative logic of existence that can be turned into imaginative forces. Art and science, as the last works of Donna Haraway (2016), Karen Barad (2007) and Laura Tripaldi (2023) explore, have gone into symbiotic networks that articulate ways of doing and being, extending the agency in general and the imaginative potential in particular to nonhuman entities.

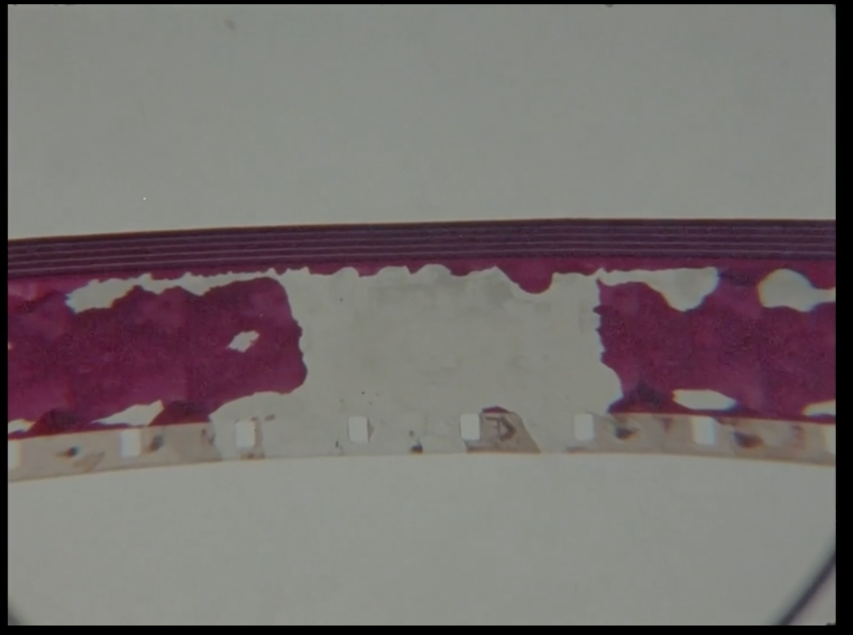

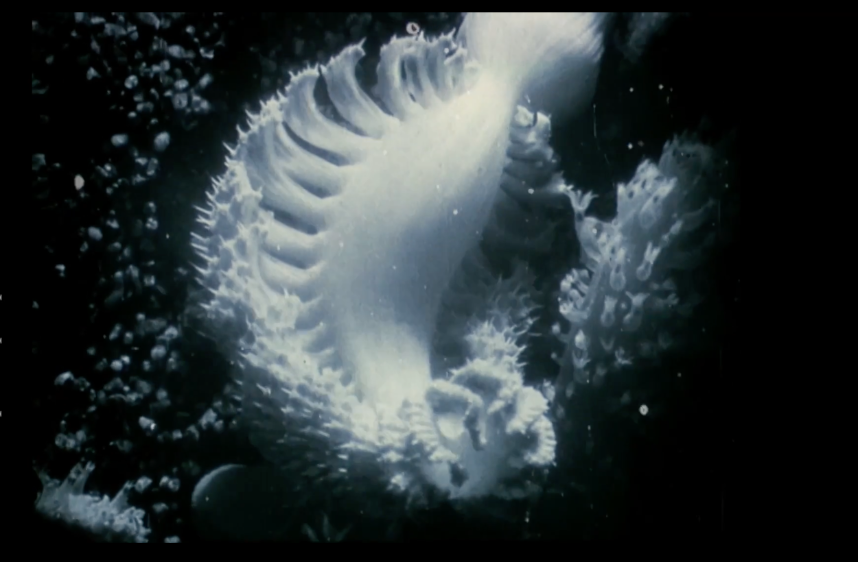

One of these changes is the recognition that thought and imagination make up technical devices such as herbaria or films. But at the same time, these devices could be thought of as the result of theories in action, that is, the concretization of a set of assumptions, ideas and hypotheses about the world. According to Vilém Flusser, the most important characteristic of technical images is the materialisation of certain concepts about the world, precisely the concepts that will direct the construction of the apparatuses that give them form (1985).3 Now, the constitution of films and herbariums as sensoria through which the modification of environments is perceived involves the agency of a material repertoire that exceeds human prerogatives. Hence the film Herbaria links the old question of the technical imaginary with the modes of existence of the mineral, the vegetable and the animal that make up the images (such as papers, emulsions, silver gel, pigments, inks, glass plates, but also fungi, bacteria and other biological agents involved in the delicate balance between preservation and destruction). In these images (see film stills), the record is inseparable from the inscription; the container could not be distinguished from the content.

The vegetal has been one of the most neglected kingdoms in philosophical thinking and the life sciences, eminently constituted from a zoocentric matrix. If we look at botanical illustrations, for example, plants appear as objects, something passive and inert; they are fixed in a simple state, isolating them from their life cycle and extracted from their milieu. As opposed to the humanistic semiotics that think about plants as ecological automata, elements available for analysis or as inanimate tools from the biosphere or the landscape, it is possible to conceive them from an ecocritical perspective that restitutes plants the capacity to narrate their own stories, to relieve the semiotic-material networks of which they are part. Giovanni Aloi writes in Botanical Speculations: “The ultimate alterity of plant-being necessitates a radical aesthetic reconfiguration to emerge along with new philosophical frameworks. It demands the will to change the way in which we look, the way in which we occupy space and time, and most importantly, it entirely reconfigures our cognitive rhythms in order to reconnect us with biosystems through new modalities” (2019: 32). Regarding what is looked at and the apparatuses that guide the gaze as a world-forming dyad in Why Look at Plants,Aloi emphasizes: “What we look at, and how we look, constitute essential parameters in the recovery of alternative gazes and in the elaboration of new ones, modes of engagement that involve more than ocular modalities that can lead to a reontologization of the living” (2019: 20).

Nevertheless, as far as technical display devices are concerned, it is important to problematize their media materiality. In general, technical images, such as photographs, video installations, and films, have rarely been contemplated in the light of their material configurations, which involve not only technical processes but also organic and inorganic chemicals, various supports and a variety of processes that make up the physical body of images. In A Geology of Media, Jussi Parikka (2025) argues that media materialism goes beyond the physical components of devices or machines. Instead, he suggests that media culture embodies a different form of materiality akin to a cosmological framework that includes elements such as earth, light, and atmosphere as media themselves. Therefore, a geology of media to which the film belongs requires a review of the layers, strata, and interconnections that underpin these media phenomena. Hence, it is imperative to explore the different modes of existence inherent to the materialities that compose them. In this sense, the materials and techniques that compose Herbaria and the way the director works them create entanglements in which the biotic and the abiotic are understood, created, and organized beyond the dualistic and oppositional models of the modern colonial West, based on the distinction between nature and culture, objects and subjects, and human and nonhuman. As a creative mnemonic practice, herbaria express a material economy in which environmental elements are managed from a logic opposed to the scheme of sacrifice and ecocide.

What kind of stories tells us about the multispecies collaborations of technical-botanical devices? An overview of the naturalist history of the nineteenth century is revealing of a colonial logic entangled in the construction of the South American botanical heritage, of the extractive media technologies that compose its visual technical devices, as well as the attempts to create restitutive memories. At the beginning of the twentieth century, Juan Aníbal Domínguez, director of the Museo de Farmacobotánicaat the Universidad de Buenos Aires, traveled to the Botanisches Museum in Berlin with a set of unpublished letters from Alexander von Humboldt to Amado Bonpland, the first naturalist based in Argentina. The purpose was to exchange them for copies of the first collections of botanists in the country, such as Georg Hyeronimus or Emil Hassler. They surveyed native flora and brought specimen to Germany, where they did the technical depictions. The duplicates of these collections are the only surviving reservoir since the originals were lost in the destruction of museums during the Second World War.

In Herbaria, this is told by focusing on the non-human semiotics developed by plants through the proliferation of meaning without representation. Following Michael Marder’s approach, plants do not think representationally or ideationally, as we humans attribute to ourselves, but with their own corporeality, nurturing, growing, decomposing (Marder, 2013: 10 ff). With respect to the extinct native species, the herbariums express, from their materiality, a memory of the light, of the darkness, of the environmental factors to which the species preserved there have been exposed. From their specific technique, herbaria present a sensitivity that captures a state of the world that is the potential cause of our extinction. In this regard, the filmic surface of Herbaria operates as a place of encounters, temporalities and knowledge, a space where a living archive is mobilised that allows us to visualise the slow violence of extractivist practices. At the same time, the plants preserved over the years serve, for example, to understand climate change in relation to human activity, but 100 years ago they were not preserved for that purpose. Furthermore, in the film, plants are placed at various points in the film strip; the animation arises during the production process. In this case, the plants are not inert objects that come to life cinematically. They are also producers and animators of the image.

In the attempt to categorize and to map what exists in the environment, the naturalist discourse finds essential traits, but Listorti’s film shows us that those differences are leaking out. There, the monstrous emerges as that which links what shouldn’t be linked, what exceeds classifications and taxonomies, and what allows one to think outside the rigid compartments of essences. The monster, from the Latin monere, means to warn, indicates the blind spot where the modern enterprise classificatory of kingdoms and species fails. Shot on 35mm and 16mm, the essayistic work Herbaria explores, within expired chemical components, damaged films, and archival material, the unpredictability of what can be revealed, that makes the image appear as it is, as a spectrum.

What does the technic-vegetable approach opens up regarding memory, looking, and thought itself? What is its political force? Maybe by approaching the ideas of Emanuele Coccia about the capacity of vegetable life to make world, we can speculate an answer. In The Life of Plants, the Italian philosopher defines plants in a double way: they are “the form most intense, most radical and most paradigmatic of being-in-the-world” as well as “the purest observer when it comes to contemplating the world in its totality” (Coccia, 2019: 12). As collective witnesses, never individuals, plants bring us closer to a kind of memory that re-politicizes the ways of seeing and expressing, making them extensive.

On the other hand, the mixture of the vegetal and the mineral, which the technical analogue images make possible, adds significant layers to the conception of a non-human memory. The glass that composes the filmic devices shows a configuration opposite to the organic world: it embodies a strange temporality which transcends organic decay. This sense of matter goes beyond minerality or vegetativeness to encompass what we commonly conceptualize as technical objects. These objects form the geological strata of the world to come, a collection of “talking fossils of the future”, as artist Juan Miceli calls them. It is a collection of technological detritus in a world in ruins that challenges us to essay new forms of critical archaeology.

Works cited

Aloi, G. (2018). Botanical speculations: Plants in contemporary arts. Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Aloi, G. (2019). Why look at plants? The botanical emergence in contemporary art. Brill.

Barad, K. (2007). Meeting the universe halfway: Quantum physics and the entanglement of matter and meaning. Duke University Press.

Coccia, E. (2019). The life of plants: A metaphysics of mixture (D. Montanari, Trans.). Polity Press.

Della Noce, E., & Murari, L. (Eds.). (2022). Expanded nature – Écologies du cinéma expérimental. Light Cone Éditions.

Derrida, J. (1995). Archive fever: A Freudian impression. University of Chicago Press.

Flusser, V. (1985). Filosofia da caixa preta. Hucitec.

Haraway, D. (2016). Staying with the trouble: Making kin in the Chthulucene. Duke University Press.

Hörl, E. (2017). Introduction to general ecology: The ecologization of thinking. In E. Hörl & J. Burton (Eds.), General ecology: The new ecological paradigm (pp. xx–xx). Bloomsbury.

Lopes Coelho, S. (2023). The entanglements between cinema and plant worlds: The unique (though plural) contributions of Latin American cinema to the debate. Rizoma: Laboratory of Art, Ecology and Science. [Online journal]. https://bit.ly/4hBvKas.

Lopes Coelho, S. (2023). The rhythms of more-than-human matter in Azucena Losana’s eco-developed film series Metarretratos. Iluminace, 35. https://www.iluminace.cz/artkey/ilu-202302-0003_the-rhythms-of-more-than-human-matter-in-azucena-losana-8217-s-eco-developed-film-series-metarretratos.php.

Marder, M. (2013). Plant-thinking: A philosophy of vegetal life. Columbia University Press.

Parikka, J. (2016). A geology of media. University of Minnesota Press.

Schwarzböck, S. (2022). Las medusas: Estética y terror. Marginalia.

Smithson, R. (1996). The collected writings (J. Flam, Ed.). University of California Press.

Tripaldi, L. (2023). Mentes paralelas: Descubrir la inteligencia de los materiales. Caja Negra.

Wiedemann, S. (2020). Em direção a uma cosmopolítica da imagem: Notas para uma possível ecologia de práticas cinematográficas. Arteriais – Revista do Programa de Pós-Graduação em Artes, 6(10). https://periodicos.ufpa.br/index.php/ppgartes/article/view/10585.

*

Paula Bertúa combines questions of aesthetics, politics and technology in her research on art and visual culture in Latin America. Her research integrates a materialist approach with critical posthumanism, media geology, and ecopolitics to contour a new perspective on Latin American artistic and collective practices, which she understands as cosmo-aesthetics.At the intersection of aesthetic practices and theoretical discourses, Bertúa explores the interventions of contemporary Latin American techno-aesthetics in relation to global political and environmental discourses against the background of regional conditions and their interplay with transnational imaginaries. She is a member of Centro de Investigación en Arte, Materia y Cultura (IIAC-UNTREF, Argentina), an interdisciplinary institute that promotes artistic and scientific research on diverse representations of Latin American visual culture.

To cite this article: Bertúa, Paula (2025) Herbaria: Essays for a Material and Postnaturalist Memory of Botany and Film, La Furia Umana, 46. https://www.lafuriaumana.com/paula-bertua-herbaria-essays-for-a-material-and-postnaturalist-memory-of-botany-and-film/

Keywords:

Download PDF

- In some of her works, Noelia Billi lucidly analyzes artistic practices concerned with the ecology crisis through a critical exploration of vegetable imaginaries. See, for example: “Plantismo del fin del mundo: Estética de la explicitud entre plantas radioactivas y flores robóticas” in Cadernos de Estética Aplicada n. 33, jul-dez, 2023. ↩︎

- The question of the materiality of archives was developed by Colectiva Materia, to whom I follow here in my analysis. See: the collective and open class, “El archivo como sensorium no humano”, Buenos Aires, Centro Cultural Kirchner, 30 October, 2020: online https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6Rd6iPTYEOo ↩︎

- For Flusser, photography, for example, quite contrary to automatically recording impressions of the physical world, transcodes certain scientific theories into images, or to use Flusser’s words, ‘transforms concepts into scenes’ (1985:45). ↩︎