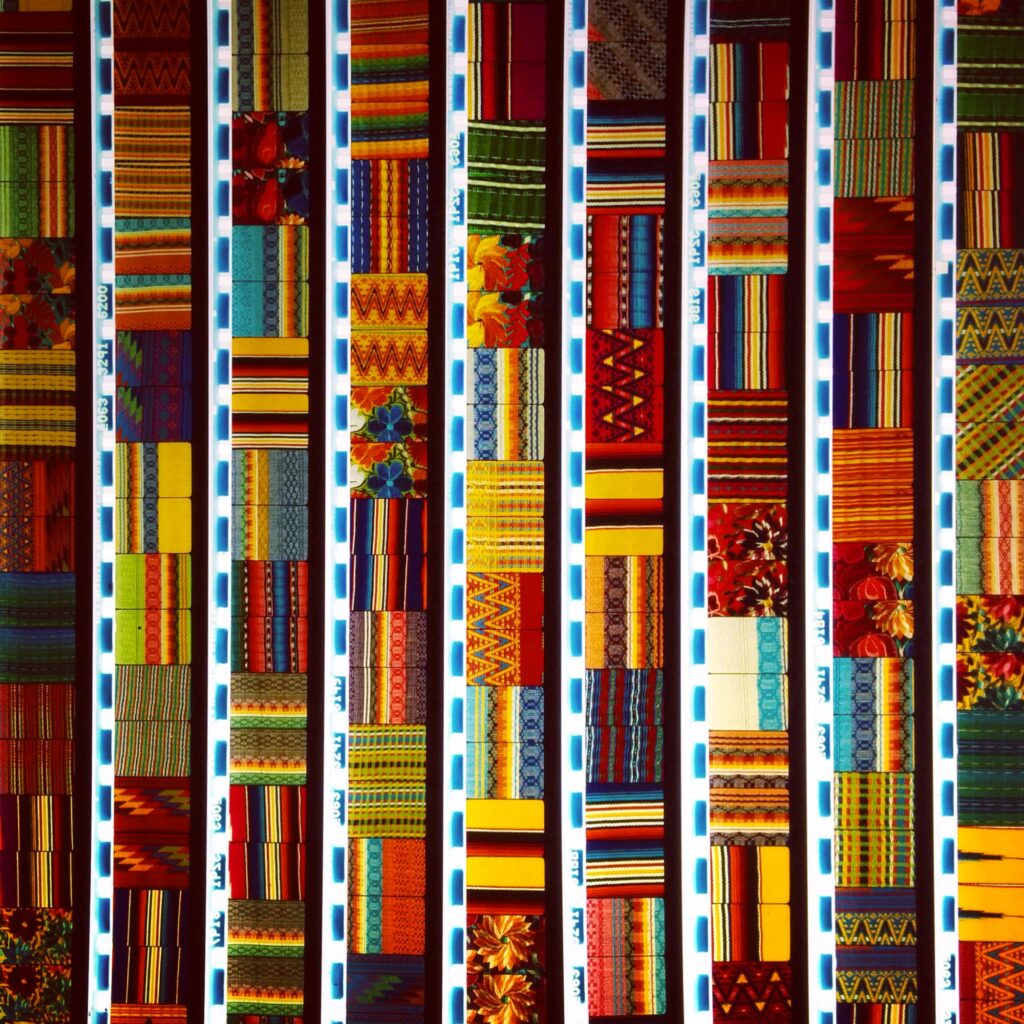

Jodie Mack, Film strips featuring textiles from Oaxaca, 2015.

Jodie Mack doesn’t really look like a sorceress but she might be one of those you can’t recognize at first sight. I met her last year in Paris when she was presenting her film program Let Your Light Shine for the first time. She was traveling the world, carrying all those gold nuggets I was lucky enough to see at a screening in some alternative artist-run space in Paris. We met afterwards in a former launderette converted into a café. As far as I can remember, she didn’t put a spell on me although her films kept on fascinating me. This might be a bewitched interview…

Eline Grignard: The current issue of La Furia Umana intends to map the experimental practices for the last decade. How do you feel about being one the ‘new’ avant-garde filmmakers ? Does it mean anything to you ?

Jodie Mack: I truly admire the history and varying trajectories of avant-garde film. So, yes, I am proud to try and perpetuate the tradition through my films and teaching! There’s something about the concepts running through this work that seem relevant today more than ever, possibly because of failed ideals.

E.G.: How would define those concepts you are referring to? How are they still relevant nowadays?

J.M.: I’m talking about the basic impulse to create experimental films: to treat time as a visual form, to connect the cinematic medium to the plastic arts (which isn’t necessarily a productive way to think about things at this point either…), to make small films and screen them in intimate settings. This feels ultra relevant today first because the mainstream utilization of time-based media (not only cinema, but television, mobile ‘content’, etc.) seem at the very core of some of the world’s greatest problems, no? An awareness of this at the layperson level could really spawn critical and community awareness that’s absolutely necessary.

E.G.:Do you feel any special connection with your predecessors, with any historical avant-garde filmmakers and experimental animators? As a teacher and filmmaker, does it matter to you to express this genealogy?

J.M.: Of course! Experimental animators – really the entire tradition mapped out in Cecile Starr and Robert Russett’s Experimental Animation, which I found in a library when I was 20 – truly fueled lots of my early development and my general approach to teaching this type of work! But, I also try to link connections for my students outside of cinema so that these connections to see how cinematic genealogy connects to larger trajectories of other histories: art, performance, literature and where those things intersect.

E.G.: Did you study film animation at school ? What is your academic and artistic curriculum? What kind of memories do you have from these student years?

J.M.: I attended an arts high school for performance and feel very fortunate to have studied acting/singing/dancing, art history, film history, playwriting, pretty seriously from age 13-17. I can’t help but mention it because it was really this incredible program – public! – that, above all things, taught the fundamentals of an artistic work ethic. We had extra classes every day, stayed until school until 11pm most nights during rehearsals, and made our own thesis projects at the end! Then, I received my undergraduate education in film and media studies, which was mostly writing. After learning about video art in some classes in contemporary art history, I found out about the experimental film while sitting in on a course at UC Berkeley in the summer of 2003. After that, by a strike of luck, I started taking classes with Roger Beebe in Florida, who provided and continues to provide inspiration, encouragement, and challenge! I then pursued a masters degree in film, video, and new media from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Now I’m here!

From these years I remember a constant sense of re-awakening, though I also remember never sleeping! I made some of my best friends in the middle of the night, hovered over computers or animation stands. There was a gigantic sense of equal promise of our medium alongside fear that the world might make us starve for doing what was right!

E.G.:Can you name some of your fellow experimental filmmakers friends? Is there any sharing and collective projects that bound you together?

J.M.: Sure! Naomi Uman is certainly a dear friend and constant inspiration of my work through her filmmaking and artistic practice in general. Roger Beebe was my teacher and is now my lifelong friend, and his influence spawned many other connections with his fellow students still working today— people like Mike Stoltz or Charlotte Taylor, who were my classmates over ten years ago and still pushing on, making work! Lori Damniano, Stefan Gruber, Kelly Sears: these are also contemporary experimental animators who I admire artistically and personally. Generally, I feel many of my peers today found experimental film through the community ethos of something like Recipes for Disaster, the zine compiled by Helen Hill. The energy set forth by that publication demands that filmmakers also work for their community by encouraging the micocinema network. And, I feel many of my peers have invested themselves in similar pursuits and extremely admirable ways. Someone like Steve Cossman, is making films while pretty much running the best place to study experimental filmmaking in New York City—independently!!! Its so beautiful.

E.G.: Most of the time, you can manage to work on your own on your film projects. Is it always the case? Did you ever work with other people (artists friends for instance)? How did you like it?

J.M.: The smaller ones I can generally handle by myself, spare some phone conversations here and there with people I trust. The larger ones take help, and my strategy has generally been to try and utilize anyone and everyone in sight during larger projects. For example, Yard Work is Hard Work contains musical performances by many of my friends from Chicago, and a few of the speaking roles were actually performed by my teachers! For Dusty Stacks, of course, I worked with many musicians and sound people for the soundtrack. And, for the shooting, when I traveled to Florida, I enlisted the help of anyone I could find! All of a sudden, my ex-boyfriends from high school were helping me build sets, my old friends were dancing with paper heads, and teenage daughters of my mother’s co-workers were helping to cut guitars! I also worked for ten days on two separate occassions, once with my friend Basia Goszczynska (an incredible animator and sculptor) and another time with Mike Stoltz (mentioned above) on the shooting. We were still just crew of two, but I coudn’t have accomplished the scenes we shot without them. During that time, I actually really started to see the value in the roles set forth by the film industry – why it’s important to have other people around taking care of the lights, helping with problems. Now that I move far beyond the spatial constraints of the animation stand at times in my shooting, it’s really just helpful to have someone there simply to click the camera while I’m running around these gigantic spaces animating. So, in some cases, I’ve made new friends through these productions. I met a friend of a friend dancing on New Year’s Eve in Mexico, and three days later he was part of my makeshift animation crew shooting textiles 5 hours away! In China, I befriended a journalist who accompanied me to a gigantic fabric district and translated for me with the skopkeepers so that I could shoot guerilla animations on the street!

E.G.: Could you give me your personal definition of the avant-garde? Is it still a relevant idea for you?

J.M.:Well, I guess I try not to get too caught up with the semantics of what we’re doing because it seems like there is potential to get lost in that vortex! So, I suppose my general definition of ‘avant-garde’, at this point, would be the support of all things ‘inventive’ while self consciously understanding that our ‘inventions’ rely upon combinations of previous inventions and thus the term ‘avant-garde’’s meaning is actually malleable depending on the medium one seeks to describe. It’s relevant to me in the sense that the term supports experimental endeavors as a way to explore outside of a capitalist model. It’s also quite handy to use as a point of entry for students or newcomers because somehow the historical isolation of the term’s roots clearly locates the intention of these methods in contrast to a budding industry. But, really, I don’t split hairs over avant-garde vs. experimental vs. cinema. I’m often too busy making it!

E.G.: As you are mentioning the capitalist mainstream model of film production, I would like you to talk about the current production conditions? Do you feel like being an outsider in the film production landscape? Can you make money from your experimental work? Is it an important issue for you?

J.M.:I suppose I don’t really feel like an outsider in the film production landscape even though I surely am one! Can I make money from my films? Well, I could certainly probably make more money from them than I do if I tried, but I like to be generous with them – giving things for free or reasonable cost, sharing the work online in many cases – even though that is not the most lucrative choice. Surely it’s an important issue because it governs the way I can make work. I’ve always had jobs; filmmaking is something I mostly do at night or on the weekends and it always has been. But, I would prefer to have a job than worry about surviving constantly while pursuing a medium that is economically unstable. Luckily I love to teach and feel that it is my duty to try and help students see cinema in new ways because it creates a lovely, sparkling environment of ideas and exploration for me and my work.

E.G.: Entering the digital era of filmmaking, why is it so important fo you to use film (16 mm mostly) as a medium although we know it’s nearly coming to an end?

J.M.: I work in 16mm for a variety of reasons: I truly enjoy the sense of economy it forces upon my shooting process; the medium renders color and texture in a unique way that benefits many of my subjects; the shutter mechanism of film projection – a different physiological experience than video projection – governs many of the strobing principles that force movement upon the eye throughout many of my films. Plus, it’s MAGIC.

E.G.: What do you mean by ‘magic’?

J.M.: Little silver halide crystals swimming around in gelatin dancing for the light and the dark!

E.G.: To what extent does film obsolescence impact some of your work?

J.M.: I suppose I see it differently. I don’t see 16mm ending; I see it experiencing multiple incantations of rebirth. I see it all the time. In many ways, the technical realities of 16mm projection today – namely the lack of 16mm in most booths and thus the need to bring the projector into the room with the audience – calls back to both the pre-standardization of cinema (actual theatre, a performance!) and the presence of the projector throughout history in classrooms, living rooms, backyards, etc. And, I think considering the beauty, the potential of this collective/live experience inspires some of my work (like audience participation in Unsubscribe #3 or Rad Plaid + performing live with Unsubscribe #4 or The Future is Bright or Dusty Stacks…). So, in this case, 16mm EMPOWERS my work and the work of others because of this power within these screening situations. They aren’t even bound within the program. Answering questions after the show; falling in love with audience members after amazing conversations about cinema and life through chance meetings; strengthening this infinitely-interesting global community of cinema-enthusiasts!!! It’s really special!

E.G.: So, it seems the screening room is also a performance set for you: can you describe your relation to the audience and how you entice people to participate to the ‘show’?

J.M.: Yes, and I think maybe some of this goes back to your question about the 16mm format. A cinema to me is a theater and a church and a classroom and a dancehall all in one! So, I like to treat the room as such! I really enjoy including the audience and asking them to participate and performing blasphemous acts considering the general etiquette of these spaces. I’ve asked the audience to do things like turn on their cellphones and test out ringtones all together, to respond vocally to the film’s images. And, some people really seem to enjoy these experiences. But, it’s not always easy to get people to play along! I try to explain and point out that we are entering a temporal partnership in the screening, that it requires generosity on the part of the filmmaker but also of the audience. I think that, again, these efforts intend to invigorate the process of cinema viewing rather than to let it die – to reimagine what can happen within this space, with people, with machines!

E.G.: I do agree with you concerning the screening room being a singular space and time, that needs to be thought each time differently. You seem to link the medium specificities of film to the ‘dispositif’ of projection. Do you think that the film screening is the only ‘dispositif’ that creates such a collective experience? Have you ever try any other way of presenting your work, in the gallery space for instance?

J.M.: Some of my works have been shown in galleries, but in many cases I haven’t actually seen the exhibitions. But, I have undertaken two gallery projects that I installed myself. One is a collection of screens actually – No Kill Shelter. Another time in Australia I mounted an installation version of my 16mm film Undertone Overture. We projected it on video – gigantic, all over the wall. And, I set up lounge chairs, like ones for the beach. It really changed the film and brought it into this entirely new context simply by interacting with these chairs and the people sitting on them! Essentially, there was a cinema inside the gallery, but it felt like the seaside with everyone sitting to watch the ocean. Galleries are interesting places for collective experiences because in many cases we just box cinemas into museums and so often spectators do not experience a similar duration within the gallery viewing experience. Still, course there are infinite possibilities outside of the cinema venue requiring physical projection. Very exciting ones!

Jodie Mack, Undertone Overture, Exhibition view, The Walls, Queensland, Australia, 2014.

E.G.: 3D effects and holographic prints are part of your cinematographic vocabulary (Glistening Thrills, Let Your Light Shine): what do you aim at when using these kind of spectacular techniques ?

J.M.: Well, I think my fascination with these materials surrounds their function as a point of entry into visual wonder that’s palatable across a wide variety of viewers. And, that’s certainly relevant to many other areas surrounding spectacle/cinema/performance/etc. touched upon within the LYLS [Let Your Light Shine] program. Light and shadow function in some of my films in strange ways because many of the planes are ultra flat/two-dimensional and lit specifically on the ‘even’ animation stand, which can make interesting effects under the camera… But, Glistening Thrills and LYLS both emerged out of longing to work differently. In Glistening Thrills, I tried to find ways to work in the real world: at the lake, in the forest, in the studio. It was summer! And, LYLS gave me a fun opportunity to experiment with drawing, mostly two dimensional impressions that were then forced into 3D space by virtue of the glasses.

E.G.: You often said that your films are ‘handmade’, an adjective that examines the tactile potential of film. What does it mean to you?

J.M: I think for my own work that term came out of starting with cameraless film and therefore aligning myself with historical modes of absolute animation that contemporary purists associate with the tactile qualities of film. These early films of mine of course have sculptural and tactile qualities as filmstrips themselves – gunky, gritty, tape-covered, candy-colored pieces of plastic! Maybe now at this point, my films contain many materials that sprawl between handmade and machine -produced practices and call attention to the tools of labor, so there’s a sense of the human body omnipresent. Just like avant-garde, I suppose, this term ‘handmade’ has become sort of a catch all for anything resisting technical or formal sterility.

E.G.: Most of your films are made out of found or recycled material, old-fashioned patterns (blankets, embroideries, tie-dye fabrics, wall papers samples). Can you describe the way you make a film out of it? Where does this material come from?

J.M.: Sure, well the sources of the material has varied over time. For my film Yard Work is Hard Work, I collected magazine material for about a year before starting the film as well as during the two years it took to make. I found things in alleys, on the internet, sourced from friends… Films like Harlequin, Posthaste Perennial Pattern, Rad Plaid, or the entire Unsubscribe Series use solely objects from my own house – sheets clothes, junk mail, etc. I made a lot of those films while in the process of moving; it was cathartic to take inventory of my belongings under the camera while packing! Lately I have worked closely with the costume shop at Dartmouth College where I teach. I sourced AMAZING COLLECTIONS of lace, paisley, and glitter gauzes with their assistance for Point de Gaze, Persian Pickles, and Razzle Dazzle.

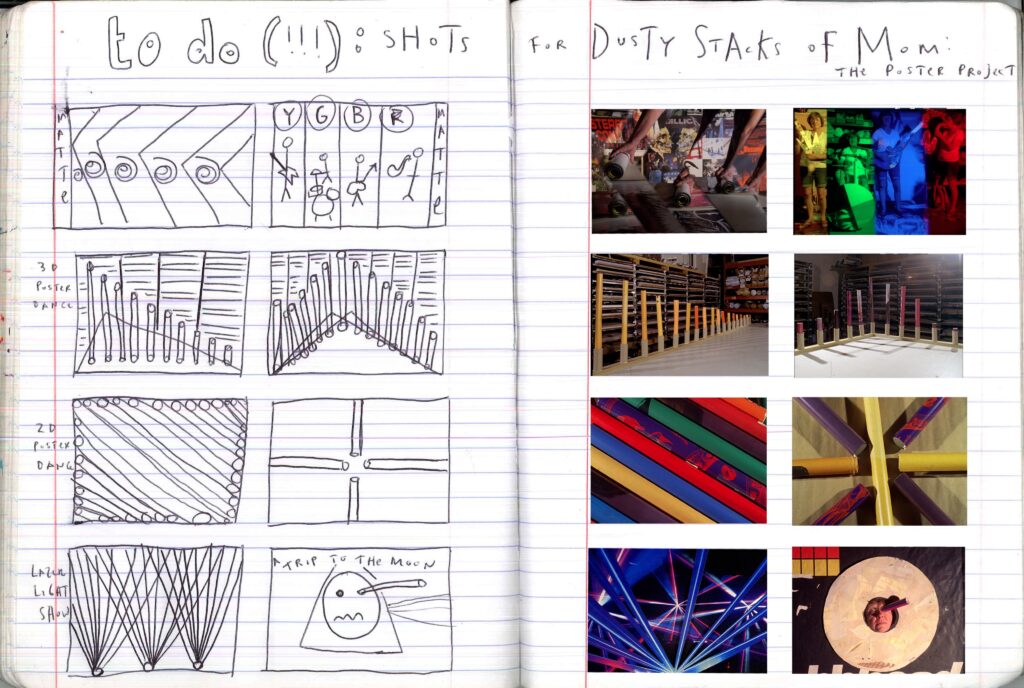

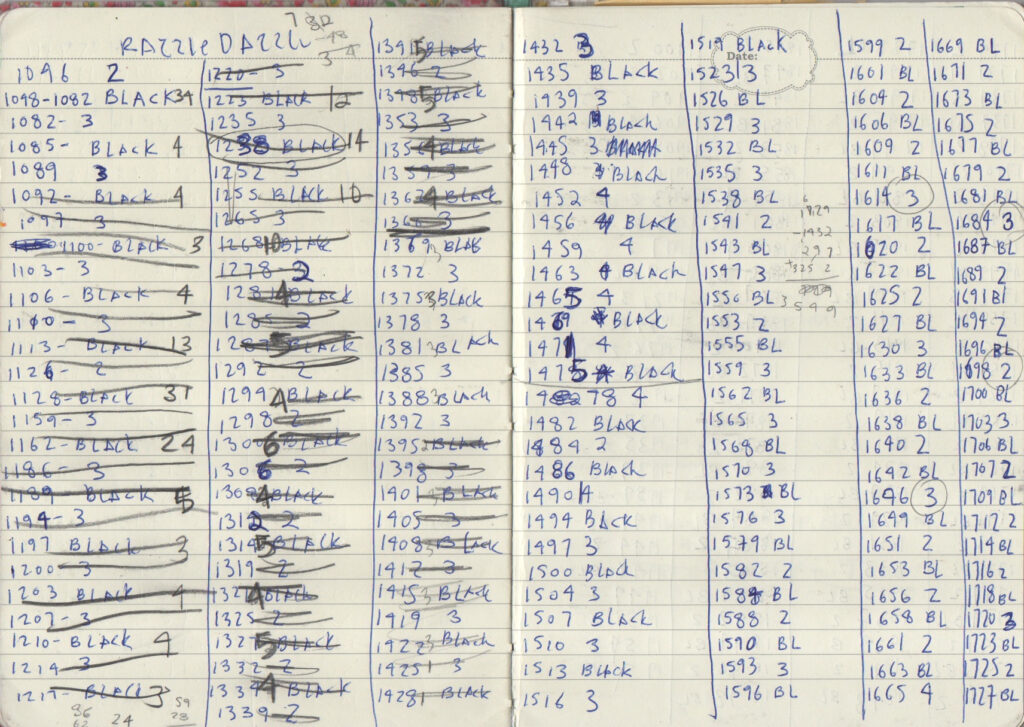

After gathering the materials, I re-arrange them in different combinations so that I can assess the potential for movement within the pieces. Then, I generally build the structure and choreograph myself a little script of numbers and notes that probably only makes sense to me.

Then, under the camera, while working through the materials, I usually find new connections and alter my plans a little – it’s sort of a combination of rigid planning and improvisation. This method only describes my short studies; the longer works require completely different strategies involving long periods of flux and confusion before clarity rises!

E.G.: I would totally agree about the inventory form you created in some of your films (New Fancy Foils, to name one) that echoes some kind of an exhaustivity concern: to make a poetic and materialist list of the documents, objects, things you collected for a given period. In what way your personal story is linked to the inventory process and how could you describe this step in the creation process?

J.M.: Well, New Fancy Foils is an interesting case because somebody, George Griffin, actually sent me all of those books as a collection in the mail! He’d had them in his studio for years and thought I could do something with them. Then I kept them for a few years, and then I did something with them! So, that particular film has this sense of an inherited collection that felt twice removed in a new way: a collection forgotten and re-activated. Perhaps it’s an interesting idea to re-source some of these materials later on in life!

E.G.: Can you talk about the long run project of Dusty Stacks of Mom? How did you get the idea of making a musical out of your mother’s “nearly-defunct poster and postcard wholesale business”, as you describe it ?

J.M: Ha! Well, to me, music seemed like the most interesting place to deal with language in this case because it provided space to deliver information while enjoying the formal properties of time – to use words as rhythms, as components of larger musical structures. I needed words to make the film, and so it seemed appropriate to siiiing them.

Jodie Mack, personal note book pages from Dusty Stacks of Mom.

E.G.: You talked about the preliminary steps and shooting phase but you never mention the editing. The idea of post-production doesn’t seem to be appropriate to your filmmaking, is that right?

J.M.: I shoot each my stroboscopic material studies in camera, so they generally have no editing in the post-production process. Larger pieces like Dusty Stacks, YWiHW, Glistening Thrills require a considerable amount of post-production work, especially with editing and sound.

E.G.: Is it also something that you undertake by yourself? Post-production?

J.M.: If something requires editing, then I do it. I work with many others on my soundtracks. Generally, though, I don’t feel the divisions of pre/post/production because these phases constantly overlap within my practice – partially because making animation takes such a long time. So, during a larger project, I could be editing one scene, shooting a scene, and planing a scene at the same time. I have an associative brain, so I often plan things with the materials I use and then leave room for new inspiration or possibilities with the remnants of different animations (cutting up paper and then animating the shreds, for example). Then, once I’ve exhausted all the possibilities in my brain, I can finally piece everything together (possibly while re-shooting certain parts).

E.G.: Then, how do you manage to bring such a sense of musicality, pace and rythm ?

J.M.: Even when shooting to edit later, I conceive of the shots very specifically with time in mind and have to make sure that the shots will fit because I try to re-shoot as little as possible. So, it often requires careful planning – scoring. This is a very tedious stage because it requires tons of simple math mapping out musical time to frame increments over and over again, but it’s essential for perfect timing. It’s sort of like doing a good taping job before you paint a room – it’s a drag, it slows you down when you want to get to the fun part, but it makes perfect edges!!!

Animation Notes from Razzle Dazzle, 2014.

E.G.: Your last film program titled Let Your Light Shine, which has been widely screened in many different countries, is a series of short films related to what we can call ‘abstract cinema’. How did you think about this program and what brings the films together ?

J.M.:The program emerged in a wild summer flurry shortly after completing my film Dusty Stacks of Mom. I performed with the piece a few times, which I’d finished to video. And, then I knew that I needed to raise the money to cut the negative for a print of Dusty Stacks and that I needed to extend certain themes addressed by the film in ways that the film itself would not let me. I needed to illustrate some concepts without language!!! So, bridged together through the lose weaving of a concert structure, the program co-explores notions of material obsolescence, abstraction, and spectacle. New Fancy Foils begins to address notions of dead capital; Undertone Overture ties aesthetic capital to abstract animation’s function within the commodification of psychedelia (while also calling attention to nature and wonderment, age old argument of art vs. nature); Dusty Stacks of Mom interweaves these themes into cacophanous confetti; Glistening Thrills mourns the cyclical role of materials (while also testing the role of music upon the emotions); and then let your Light Shine sets the cinema on fire, celebrating the power of pure animation and

collectivism !

E.G.: You seem to be interested in combining different approaches: not only abstract and decorative art, handicraft but also graphic design, film genres and storytelling. Is there any political and social statement in doing so?

J.M.: Yes, that’s true; all of those approaches surface. I suppose I feel sometimes like I’m playing to multiple sides: a hardened and stoic experimental scene and complete outsiders. And, back to your questions about cinematic quantifiers, I don’t see these distinctions of objects or of cinema as that different – it’s all material. As for politics and social value, well, of course, we’d need to define those terms as well. But, maybe it seems to me that at one point, a gesture towards the abstract film was clearly a political gesture and call for media literate audience. Today, it is more complicated, as many of the distinctions you list also exist in other hybrid definitions – it’s a slippery surface. So, I don’t discriminate materials or genres; they are all equally important in my quest as equal parts filmmakers and educator: cultural worker!

E.G.: You told me once that you don’t understand why some people despise abstract films although they are surrounded by patterns, colors, forms in their everyday life? Is it something you care about: to intermingle formal purposes with an aesthetic feeling that can be aroused at home and common places?

J.M.: Ha! I hadn’t really thought about it like that! I suppose I believe deep down that looking around your house or down at the carpet in a hotel can illuminate many truths about how culture perceives the role of art and decoration in our daily lives – and how this is connected to a large string of harsh economic and political realities. But, surely, I hope that my films will instill within the viewers, the sense of imagination necessary to make the patterns on your sofa dance!

E.G.: What are your upcoming projects? Next screenings?

J.M.: Upcoming, I have a screening of the Let Your Light Shine program in Paris at La Videoshop, organized by Bill Brown and Sabine Gruffaut. My film Unsubscribe 1 is also currently touring in Warsaw, Instanbul, and Paris. And, I will share some films this summer both at Phil Hoffman’s Film Farm and the ACRE artist residency. Because I am now trying to go into full throttle with my new projects, I will not be able to travel as much until this is finished! But, here in the mountains, I am cooking up some things!!!

Both of my current projects resulted from images captured while touring with the LYLS program. I am working on something of a rainbow lovesong called Something Between Us. It’s a study of cheap costume jewlery and light throughout a series of interior and exterior treatments. I shot different parts of it in Australia, London, Shenzhen, Buenos Aires, and also here at home in New Hampshire. It’s about…energy (!) – feeling very close to someone who is far away, or feeling very distant from someone right next to you!

But, that’s just a small thing! I’m also working on much larger project that will draw parallels between the development of fabric production alongside the dissemination of language and the spread of global culture. It’s an animated travelogue, an experiment in stroboscopic “ethnoGRAPHy”. A kinetic journey through the graphic motifs of textile practices pairs figure and landscape to research abstract design, systems of language, and strategies of conveying information in documentary. Or something like that. It started when I traveled to a weaving village in Oaxaca and started animating with fabrics there… Since then, since traveling more and noting the similarities of motifs across multiple handmade and machine weaving practices (alongside their appropriation via printing), the project has expanded exponentially. As I said before, I went to China and animated in a gigantic garment district (still finding the same motifs!). And…now… I am working through all of this, tying it together in my own way. I’m wondering: How do visualabstractions function as part of complex visual systems? How does the dilution ofornamental design relate to the dislocation of language? In which are the ways we cancompare the basic components of visual symbolism with those of language? Do patternsof linguistic dilution mirror those of pictorial language symbols? So, yes, I’m reading, shooting, composing, and trying not to worry too much about accomplishing the impossible!

Eline Grignard