by Jean-Michel

(discovered by Mark Rappaport)

No, I wasn’t in the Resistance and, yes, I suffered, as did everyone else I knew, during the war—in my business especially, since everything was rationed and there were severe flour shortages, I couldn’t make bread. And, of course, if I didn’t bake bread, I couldn’t sell it. But the war aside—those stories for another day—I never expected much out of life, and subsequently when bad things happened, I just assumed it was part of the natural order of things. Similarly, when good things happened to me, I accepted them graciously but was not inordinately surprised. It was all part of the way of the world, I guess, and I took the blessings as well as the miseries with equal equanimity. I never went out of my way to acquire prestigious things, nor did I have any unfulfilled dreams that would propel me out of an ordinary life, seeking the kind of rewards or achievements that elude most people. But sometimes wonderful things happen to you when you don’t expect them or ask for them or even dream of them. If you’re sitting under a peach tree in the summertime and ripe peaches fall into your lap—well, consider yourself a very lucky fellow. And, in at least one respect, I was a very lucky fellow indeed. As I suggested, I had no particular ambitions. Since I am not credited in the movie or in the history books and since my name would mean nothing to you, let us just call me Jean-Michel and leave it at that, since every person must have a name as well as a face (about which, more later). But please be aware that I, Jean-Michel , was, for a variety of reasons and more specifically, for the one I’m going to tell you about, a very fortunate man.

We are all part of history even if we don’t make history. But sometimes history reaches out and chooses us for an otherwise unasked for role.

Monsieur Cocteau’s phone call was that for me. Without that, there would have been no record that I ever lived or that I, too, like the rest of you, had ever existed. So, I’m a half-erased smudge on a page of History. That’s not too bad for five days of low-paid work, having your throat and nasal passages scraped raw by a thousand cigarettes, and being strapped into a torture chamber of a machine.

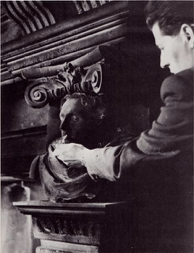

You should have seen the auditions of the “extras.” For the audition, they mostly wanted men—with strong arms. This was for the scenes with the walls from which arms holding candelabras were extended. Everyone had to strip to the waist—to audition our arms! It was like a beauty contest, but for men only. A room full of half-undressed men who didn’t really know why they were there and especially why they were asked to strip. It felt like we were being conscripted for the army. Or the Boy Scouts. Even after it was explained to us very carefully, none of us knew what the final effect would be except for Monsieur Cocteau himself, and even he, though usually quite articulate—sometimes you couldn’t even get him to shut up— had difficulty in making it clear to us. They didn’t want anyone who was too muscular. On the other hand, they didn’t want anyone too puny, either. Those with hairy forearms need not apply. The same goes for excessively beefy types. And no nail biters, please! He had a very specific idea of what he wanted but could only convey it in negative terms. If you weren’t what he wanted, you were eliminated. Even though I’m a baker and have to lift huge bags of flour and carry heavy trays of dough, my arms are short. And I have very girlish hands. At least, that’s what Monsieur Cocteau said. But he liked my face and suggested I might be interested in playing one of the hermes on either side of the fireplace in the Beast’s castle. He had to explain to me what a herme was. It turns out it’s like a caryatid, you know, a support structure in a Greek temple, a column in the shape of a woman. But the male version was called a herme. To be quite frank, I had no idea what he was talking about but I agreed anyway since it seemed like a rare moment to do something in my life that would never have been possible otherwise. Besides which, my wife was movie-struck and would have given anything to meet Jean Marais. She insisted I not turn down an opportunity like this. An opportunity for what, I asked? She smiled and didn’t answer.

At first, I thought it would be like one of those things at the fair—you stick your head through a hole in the painting of a sailor rescuing a mermaid or a cowboy lassoing a horse and then they take your picture. It was more complicated than that. Basically, they built a stand-up coffin for me that tapered down so severely, I couldn’t even stand up in it. I had to be supported on a improvised prie-dieu which they fortunately provided for me and with knee pads that went with. And, of course, there was a space for my head. But it still was a vertical sarcophagus that was several sizes too small. Even though the front of it—and this is all that the viewer will ever see—looks like an elegant fireplace, very manicured and finely detailed, the back was an improvised assortment of towels and rags to prevent me from leaning against the makeshift lumber and plaster construction. It was as if you walked into an antique store that had a very elegant display window fronting the street but as soon as the door closed behind you, you realized you were in a tacky junk shop where everything was covered with dust and cobwebs. In addition to which, they really did have a roaring fire in the fireplace, so that it was unbearably hot, to boot. They slathered my face and hair in some ungodly mixture of clay and sand and plaster of Paris, trying to emulate the color and texture of stone, and of course when I was in the contraption I couldn’t move. On the plus side, I did get a few close-ups of my very own. They even rigged up two very little lights that shone directly into my eyes so that when I opened my eyes wide, they seemed to be glowing. The whites looked phosphorescent. I think they did the same thing with Marais, when he was the Beast. Later, when I went to see regular movies in the theater, I noticed that they did the same thing to Joan Crawford in her movies!

Pity the poor guys with their arms jutting out of the walls holding the lit candelabras. No close-ups, no one got to see their faces. Ever. Can you imagine telling your grandchildren, “Mine is the third arm from the left”? After thirty years, how could you even be sure of that? Maybe you were the fourth, or. Not only could they not see what they were doing but they had to hold their arms steady and at the exact angles for many minutes at a time. An assistant had to come over each time between takes to arrange each individual arm so that it looked like they were all part of the same mechanism. Precision dancing or synchronized swimming—but for disembodied arms that had to look just so, for the camera. Nor would I have liked to have been the arm that was the designated wine-pourer at the elaborate dinner table.

Imagine being scrunched up like that for hours under the table but your arm would have to be in exactly the right position to pour the wine, on command. Ouch.

Monsieur Cocteau was above all a gentleman. Even though it seemed from interviews that all he ever talked about was himself, in person he was quite charming and made you feel as if you were very important. He tried to draw you out and talk about things that he thought might interest you. For example, he asked me about my secrets for making baguettes and croissants, since each of us bakers have slightly different recipes, which we guard religiously and persuade ourselves to think that we and we alone have the one true recipe. The fact that he was slightly cross-eyed was a little disconcerting. One was never sure quite where he was looking, but it also gave the effect that he was focusing all of his attention on one particular feature of your face. Like the bridge of your nose—even though you knew he was probably looking into your eyes. When he talked, he moved his hands constantly, as if he was telling an alternate story, just with his very graceful hands, like he was rehearsing a puppet show he was going to perform later. I didn’t mind telling him, since, because he was in a completely different profession, there would be very little chance that he’d ever use the information. But just to be on the safe side, I omitted one or two important steps. You can never be too careful. While I was telling him about how we make the bread at my bakery, he casually dropped his hand, light as a spider’s web, as if it were suddenly too heavy for his wrist, onto my knee. He let it lay there as casually as if it were a frequent resting place for his weary hand, but since I knew he was a gentlemen, although I also was quite aware, as was everyone else, about his peculiarities, I didn’t want to embarrass him by even so much as admitting to notice it. It would have been exceedingly rude on my part to suddenly, for example, try to cross my legs, calling attention to his seemingly meaningless action, as if it had been an intended indiscretion. After a few seconds while his hand rested on my knee, while feigning nonchalance, although words were catching in my throat and I had a very dry sensation in my mouth, he started rubbing it gently like it was a dog that had rolled onto its back, exposing his stomach to his master. I respected him too much to express disapproval or tell him to stop it, but I knew it would be better to indicate that I did not entirely approve instead of tacitly acquiescing by pretending nothing was happening. I feigned a sneeze and then reached for a handkerchief. It was in my right pocket just above the knee Monsieur Cocteau was so nonchalantly but nevertheless assiduously messaging. He withdrew his hand, not quickly or suddenly—to do so would be admitting a form of guilt of which he would not have been capable —as if he was aware that he was doing something wrong, but as if he suddenly realized that he had other things that he had to do with his hands, like light a much- needed cigarette. I admire his seeming savoir faire and his discretion, as much as I’m sure he admired mine. I would have to say that he never did anything like that again and remained as cordial to me after that as he had been before whatever didn’t happen had happened.

I don’t even know how to describe this. On the five days that I was on the set and they were filming, they decided not to use me and the other fellow, the other side of the fireplace—I can’t even remember his name now although you’d think I would, since we were like brothers in this strange and unique adventure together, but I guess his name is no more important than my name—if it was a very wide shot and you couldn’t see the fireplace very clearly or there were not to be close-ups of either of us. I felt very offended.

Didn’t they like me anymore? Maybe I had displeased Monsieur Cocteau or the cameraman somehow? They laughingly explained, No, no. It’s not that at all and then told me why I wouldn’t be needed. It wasn’t personal. But that’s how proprietary I had become. I wasthe herme on the screen-right side of the fireplace and no one could replace me, and certainly not a painting of my face.

Apparently, when they make movies and they do the reverse, over-the- shoulder shots, they expect the main actors to be present, even if they’re not on camera, to give the line readings to the actor who is being filmed. It’s considered courteous and professional. Sometimes, the really big movie stars, the unpleasant ones, refuse to do that. They think it’s beneath their dignity and not worth their time. And the actor being filmed has to soldier on alone, even if he feels insulted or demeaned. If it makes any sense, that’s the way I felt when they said I wasn’t needed for the very wide shots. Because they wouldn’t see my face anyway. Did I really need a few more hours of suffering? I couldn’t help it. I felt offended anyway. I was the herme or the caryatid and I was being denied my herme-ness.

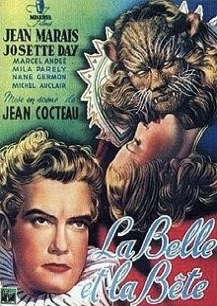

But we, the living statues as we were called on the set, weren’t the only ones who suffered during the making of the movie. Jean Marais had to be in the make-up chair for four or five hours every day to have his Beast face and hands applied. And then he could barely move for fear of disturbing the makeup. He couldn’t eat solid foods. Everything had to be pureed for him and he drank liquids through a straw. He was clearly very uncomfortable in the Beast makeup but he never complained. He kept to himself and never talked very much when he was in his full costume as the Beast. Monsieur Cocteau, as if to outdo Marais in suffering and disguises, had a seemingly very painful outbreak of eczema on his face, a boil on the back of his neck, as well as an abscessed tooth, almost as if to show Marais that he too was suffering.

Perhaps he had to punish himself for making a great work of art and for enjoying the process of creating it so much. Or maybe, on a more subtle level he was sympathizing with Marais hiding his face and he too hid his face, behind a mask of sores and boils.

Monsieur Cocteau asked me if I could exhale cigarette smoke through my nose because he thought it would be an interesting effect. Even though I had had asthma as child, I agreed to do it because, well, he wanted me to. So while I was strapped into that infernal machine, that straightjacket of a fireplace, someone would have to give me the cigarettes to puff on because I couldn’t move. I was force-fed cigarettes, like guinea pig! Take after take. The result was that it cauterized the inside of my throat and nasal passages and I’ve had respiratory ailments for the rest of my life.

So, it was an army of people who suffered on the same set in order to give birth to this strange and wonderful movie. It’s all so very strange to me that when you see the movie, you don’t see the suffering and the pain behind every frame but only enjoy the pleasure of what appears to be so magical and effortless on the screen.

Although this was a fairy tale and light as a soap bubble, when we were shooting—this was in late November 1945—aside from the physical discomfort so many of us endured, there were many, many power outages. Sometimes the electricity would shut down five or six times a day, sometimes right in the middle of a shot. There were whole stretches of time when we couldn’t shoot at all. It was a very powerful reminder that we had been an occupied country for five years and we were still feeling the aftershocks of the war. Life had not returned to normal. We were a country still living very much in the shadow of a war. The war was still with us. Even if we didn’t want to admit it, the power outages forced us to acknowledge it. There were days when the crew didn’t dare submit the negative to the lab for fear that, if the power went out during the developing process, the negative would be destroyed and everything that had been shot the previous day or two would be lost. Equally grim, during the time that I was playing the herme on the screen-right side of the fireplace, the Nuremberg trials were being held. Every day we would read in the newspapers ever more shocking accounts of what happened during those awful war years. One of the bitter ironies that somehow was related to making our fairy tale of a movie was that other movies, showing the liberation of the concentration camps, made by George Stevens and Samuel Fuller, were shown as evidence during the trial of Nazi brutality. In some way, it suggested how powerful movies were and hinted at the many ways that they could be used and made useful. It was all very sobering and in some strange way very encouraging to us to do the best we could.

It was no secret, of course, that Marais and Monsieur Cocteau were a couple, and, though both of them seemed very polite and mild-mannered most of the time, sometimes the tension on the set was so great, what with the erratic power situation, compounded by the usual problems that happen on a set, intensified even further by the fact that both of the gentlemen were in pain and suffering under their respective masks, one applied from the outside and one, Monsieur Cocteau’s, a kind of revenge that his body took on him, from the inside, they started shouting at each other. The distinctive speaking voices of each of them temporarily disappeared. Monsieur Cocteau no longer had the mellifluous tone he always had, as if he was declaiming his own poetry and spewing epigrams ready to be printed. Marais no longer had the purring growl he cultivated as the Beast. They were both screaming at each other at the top of their lungs, in shrill unpleasant voices. In fact, they were no different from my wife and I when we quarreled, except that we were not famous artists. Everyone was embarrassed for them and averted their eyes as if they had something more important to look at. After a few unpleasant volleys and suddenly realizing they were not at home, they both calmed down and everything returned to its normally abnormal state. Without apologizing either to us or to each other, they both looked around as if they had awakened from a trance and went back to work as if nothing had happened.

I was sorry when my few days were over. I felt as if I were part of a community that was bound together by an experience that we couldn’t share with other people, and that others, no matter how hard we tried to explain, would never be able to understand. And now I had to say goodbye to all these people. After the filming ended, I went back to making my baguettes and croissants and pastries and tended to my family and, like everyone else, got older.

Of course, the children got bored with it and you couldn’t get them to watch it every year on my birthday, or on their birthdays. In fact, it wasn’t even available to be seen that often. Maybe every two or three years at the ciné- club. But as I said, once the children saw it, they didn’t feel any need to see it again. Besides which, they knew me as their father who kissed them good night or scolded them when they misbehaved. Seeing me in my sculpture make-up was perhaps confusing and disorienting. I and my wife, on the other hand, could have watched it every other day. But then it became something my grandchildren could see. Strange to say, they were more interested than my children, maybe because their grandfather was so much older and much further removed from their daily lives. By the time my grandchildren had children it was, of course, another story. Even within the confines of our little family, my brush with fame, however slight, became part of the family legend. When my grandchildren bought the tape to show to their children, that is, my great-grandchildren, they wanted to watch the film every weekend. Not merely because I was in it, although, that, too, was a factor. Their relationship to movies was quite different than ours had been. You could watch it at home.

You could stop it and start it whenever you liked. You could watch favorite sections over and over again. It seemed like a more democratic way to watch movies than the inflexible starting times at the local movie theater subjected you to, tyrannical starting times which had to be obeyed. My youngest daughter told me that her eldest daughter would want to watch my scenes over and over again. In the film, I was no longer this forbiddingly old frail man whom she was a little afraid of because he was so old. To her, I was just this cranky aged creature who was distantly related—too far back even to puzzle out—to her mother, and who looked nothing like the young man that she saw in the movie. Who could explain and who would even want to try—that kind of mystery to a young child, how a face gets more and more tired, dragged down by its wrinkles, and pulling away from its skeleton, no longer remembering its former self or selves—and certainly disguising itself from the young face it once used to be? And even if you could explain it, would any child believe you? I was just a face in a movie that she loved, a family myth that had nothing to do with the somewhat scary old man that she has to kiss, whether she wanted to or not, on both cheeks at those rare family reunions and a family myth that linked her to another, larger world. It’s a legacy, of a kind… There are worse legacies you can leave behind you after you’re gone.

The other guy, on the left side of the fireplace.

Mark Rappaport

marrap@noos.fr July 2012