Introduction1

In his study on the life of plants, Emanuele Coccia argues for the necessity to overcome zoocentrism in philosophy by including plants as a fundamental element to what he calls a “metaphysics of mixture”. In this proposal of metaphysis, plants adhere to the world in an absolute way, are permanently exposed to the surrounding environment, and transform and enable changes in other living and non-living beings:

One cannot separate the plant—neither physically nor metaphysically—from the world that accommodates it. It is the most intense, radical, and paradigmatic form of being in the world. To interrogate plants means to understand what it means to be in the world. Plants embody the most direct and elementary connection that life can establish with the world. The opposite is equally true: the plant is the purest observer when it comes to contemplating the world in its totality. Under the sun or under the clouds, mixing with water and wind, their life is an endless cosmic contemplation, one that does not distinguish between objects and substances—or, to put differently, one that accepts all their nuances to the point of melting with the world, to the point of coinciding with its very substance. We will never be able to understand a plant unless we have understood what the world is. (Coccia, 2018, p. 13)

This article examines the possibilities of interaction between plants and the technologies of the image, focusing primarily on experimental cinema and, more specifically, on the filmography of Argentine artist Claudio Caldini (Buenos Aires, 1952). Before delving into a more detailed analysis of his oeuvre, we will explore some crucial moments in the relationship between cinema and plants in non-narrative cinema. After this historical preamble, Caldini’s work will be discussed in the broader context of Argentine experimental cinema. Finally, an analysis of his short film Ofrenda (1978) will conclude the examination of the interactions between the natural world, technique, and ways of observing the world.

First Cinema as Experimental Cinema

We have been thinking about how experimental cinema has always had nature and its specifically non-human elements as a central point. In fact, photographic and cinematic techniques themselves also originated from an interest in recording, describing, and understanding the natural world. We need only to recall, to cite the most basic examples, Anna Atkins’ pioneering work in botanical photography or the experiments of Eadweard Muybridge and Étienne-Jules Marey with chronophotography to investigate animal and human movement. Pre-cinematic technologies are deeply intertwined with this gaze toward the non-human, which perhaps begins with a scientific inclination, but that simultaneously and immediately acquires an aesthetic dimension.

From the beginning, there was in fact a more specific and evident focus on animals. Indeed, both human and non-human animals move at a pace millions of times faster than plants. Strictly speaking, plants do not move: they grow, spread, wither, and die slowly, silently, and mysteriously. Initially, cinema incorporated plants through science. Scientists realized that cinema was a medium capable of capturing images of this silent movement, this growth, and all these changes in plants.

Early cinema was fascinated by plants. The technology that made film possible offered a window into a realm that had hitherto eluded human perception. Scientists were quick to realize the potential of the new medium to enhance their understanding of the vegetal world. (Vieira, 2023, p. 1)

The earliest phase of cinema is thus marked by an investigative drive, both of cinematographic technique itself and of botany. This is the case with the films of German botanist Wilhelm Pfeffer, who made four films between 1899 and 1900 to study the movement of plants through experiments conducted primarily with flowers at the University of Leipzig.

Another film that explores cinematic techniques to record plants growing was The Birth of a Flower (1910, Frank Percy Smith). The same time-lapse technique employed by Pfeffer was used to capture the intrinsic poetry of petals opening under the influence of light. However, this film had high attendance during public screenings, marking a turning point in the career of its director. The impact of this type of film was quite relevant for an audience that was still discovering the full potential of cinema, prior to the establishment of narrative film. Jenny Hammerton describes the film and the mechanisms Percy Smith used to record it:

We see the following plants bloom before our very eyes: hyacinths, crocuses, snowdrops, neapolitan onion flowers, narcissi, Japanese lilies, garden anemones and roses. Smith modified his cinematography set-up with candle wicks, pieces of meccano, door handles and gramophone needles to film these flowers in motion. He set up a system whereby growth could be filmed even while he slept, a large bell being set to ring and wake him if any part of the process malfunctioned. (Hammerton, s/d)

Percy Smith was one of the most outstanding representatives of what we might call “scientific film”, or even “educational film”. He dedicated much of his career to the Secrets of Nature series, which he produced to British Instructional Films. Among the numerous films on the series, the short film Floral Co-operative Societies (1927) shows the sexual elements of pollination in flowers such as dandelions, daisies, star thistles, and everlastings. The film is a more sophisticated example of the techniques already developed in The Birth of a Flower and, like the latter, has a significant popular appeal due to its aesthetic values.

With endless patience, he could spend up to two and a half years to complete a film. He also had the popular touch, with the happy knack (as he put it himself) of being able to feed his audience “the powder of instruction in the jam of entertainment”. (Dixon, s/d)

The first decades of the century were crucial for establishing the relationship between cinema and botany, and maybe in this sense, the most emblematic film of this period might be Blumenwunder (1926, Max Reichmann). Using similar techniques to the filmmakers cited above, but perhaps with greater conceptual complexity and further structural ambition, the film deepens the connection between technical experimentation and botanical investigation.

Time is again of the essence here, as the film reveals the gap supposedly dividing the animal and the vegetal realms to be merely a matter of a temporal misalignment to be disentangled through cinematic means. (Vieira, 2023, p. 1)

This historical preamble aims to demonstrate that the link between early cinema and plants may possibly be foreshadowing what would later be called experimental cinema. All the examples mentioned above lie at the frontier between the scientific and the aesthetic, in each case the experiment (whether related to the techniques of the visible or in relation to the scientific object that it proposes to explore through film) is invaded by the ineffable of the sublime. In a certain way, that might be a good definition for experimental cinema: when aesthetics surpasses the realm of technics.

Gardens, hedges, collages, bouquets, trees…

Thus, if cinema has always been configured as the ideal medium for establishing a complex visual relationship with the natural world, it seems evident to us that the more specialized domain of experimental cinema is precisely the territory in which this relationship is most fully realized. We will discuss now some crucial moments involving plants in experimental cinema, emphasizing that it is not our intention to provide a comprehensive inventory of all films produced in this field, but rather to highlight a few key titles that contribute to reflecting on this tradition.

Let us start with Glimpse of the Garden (1957, Marie Menken), that, for example, explores both the big view and the small details of a garden. Menken employs a montage of images that unveils the hidden secrets of the surrounding vegetation, taking us on a journey through textures and details—from trichomes to protrusions and grooves on the plants—transforming this hidden microcosm into an expanding universe.

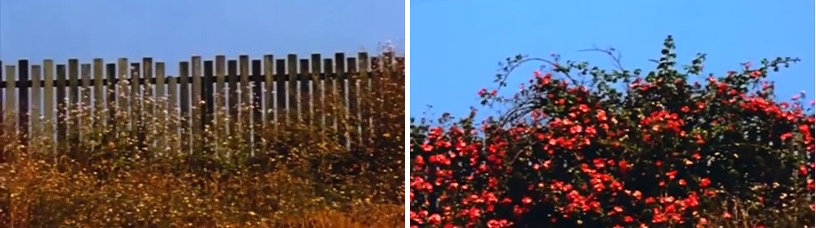

Almost ten years later, Bruce Baillie made one of the most famous experimental films, All my Life (1966), a tracking shot of a slatted fence, framed by the bright blue sky and a field of dry grass, along with the title song by Ella Fitzgerald on the soundtrack. As the film progresses, the fence becomes increasingly taken by a huge vine of red flowers:

In many respects, the image is perfectly ordinary, the kind that you chance on if you’re driving along, say, a California road, as Mr. Baillie was when he popped out of a car, seized by inspiration. Yet, as the camera continues to float left and Fitzgerald begins singing (“All my life/I’ve been waiting for you”), something magical — call it cinema — happens in the middle of the first verse. As the words “My wonderful one/I’ve begun” warm the soundtrack, a splash of red flowers on the fence suddenly appears, as if the film itself were offering you a garland. (Dargis, 2016)

Further ahead, we have more new possibilities for “botanical” cinema: in the early 1980s, another experimental classic, The Garden of Earthly Delights (1981, Stan Brakhage), was created. In this film, the artist arranges various types of leaves, seeds, roots, and flowers into patterns between two strips of 35mm film, later optically printing them:

The material is the result of the physical encounter between two organic bodies that the artist merges into a single entity. During the creation process, Brakhage does not exercise precise control over the animation he is creating. Thus, the films present themselves as the outcome of a process in which the artist explores the tension of a potential encounter between cinematic vision and non-human existences. What we see projected is the residue of the creative process that produced it, just as seeds, flowers, and petals are organic residues of the natural biological processes that occurred within the artist’s microcosm. (Melo, 2022, p. 59)

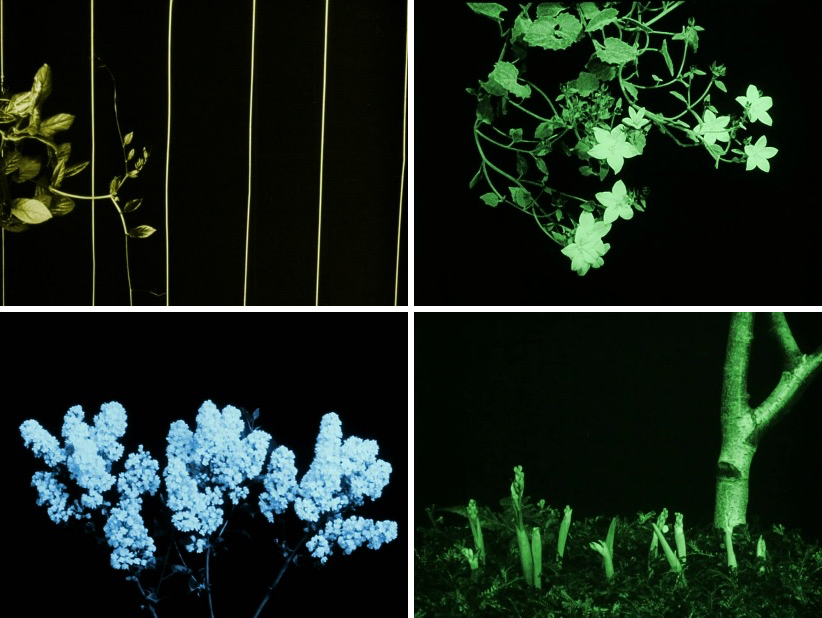

Like Brakhage’s films, the work of Rose Lowder adds a radical materiality to film medium, always articulated with many aspects of natural environment and vegetation. In her most famous series, “Bouquets”(1995-2010), she developed a technique of in-camera montage, captured frame-by-frame to form meticulous patterns of light, resulting in a singular and instant flicker effect:

Colors, objects and their treatments go beyond the discourse of scientific research that the filmmaker usually tends to maintain. We cannot ignore the high sensuality of the scenes and their choices. Rose Lowder favors scenes of nature, even though some of the sites filmed are located in the city. Through their filmic transformation, they no longer appear to be urban manifestations but natural landscapes. In this way, Rose Lowder continues an impressionist tradition: working in nature rather than in the studio; like Cézanne, working on site is the sine qua non condition in order to reveal the ‘little sensation’ and represent it. (Beauvais, s/d)

The link between experimental cinema and the world of plants, however, is not constituted only by details, fragments, or close-ups. Trees can also be the object of a more distant view, a point of entrance to the big brave world. The very own idea of landscape can be implicated in this way of looking at plants. Larry Gottheim, for example, made a beautiful film called Fog line (1970), in which he shows a landscape in the mist in only one 11-minute shot. The mist changes the landscape and evolves the trees and all the territory.

FOG LINE is a wonderful piece of conceptual art, a stroke along that careful line between wit and wisdom–a melody in which literally every frame is different from every preceding frame (since the fog is always lifting) and the various elements of the composition–trees, animals, vegetation, sky, and, quite importantly, the emulsion, the grain of the film itself–continue to play off one another as do notes in a musical composition. The quality of the light the tonality of the image itself–adds immeasurably to the mystery and excitement as the work unfolds, the fog lifting, the /film running through the gate, the composition static yet the frame itself fluid, dynamic, magnificently kinetic. (Foery, s/d)

Our last example, before a further analysis on Caldini’s oeuvre, is Alberi(2013, Michelangelo Frammartino). With a very different perspective from Gottheim’s distance, Frammartino inserts himself in the forest, almost like in the ghost rides from the beginning of the twentieth century (in which a camera was put in a moving train), the landscape is ripped apart. The spectator has the impression that they’re moving together with the camera, almost feeling the leaves, branches and thorns of the vegetation.

Alberi (which translates as “trees”) is a work designed to evoke the sublime. With its strange visions of vegetal creatures and spectacularly grand landscapes, Frammartino’s immersive work offers a unique experience—by turns playful, slightly menacing, and ultimately celebratory. Structured as a continuous loop, the piece begins and ends in total darkness. It’s a smart choice that immediately sensitizes the viewer to the world of ritual and nature through a powerfully tactile and elemental sound design. (DALLAS, 2014)

Caldini and Argentinian Experimental Cinema

Arlindo Machado (2010) attempted to provide a panoramic overview of the history of experimental cinema in Latin America, pointing out the enormous difficulties in finding material, both in terms of critical reflection and the works themselves. Reflecting on experimental cinema in Latin America would, for him, involve a dual challenge. First, due to its origin in the region, these forms of expression would be largely unknown, with scant distribution, limited access, minimal information, and little critical analysis stemming from a lack of global attention. Second, because of their experimental and non-commercial nature, they would already be ruled out in advance anywhere else. Nonetheless, Machado’s short text is an interesting starting point for thinking about the tradition in the region in general, pointing more specifically to some Argentine examples, both films and thinkers of this type of cinema.

In the article, for instance, he mentions what could be considered the first example of Argentine experimental cinema, the film Traum (1933), even though it emerged from a collaboration between photographer Horacio Coppola and the German Walter Auerbach, and was made in Germany. Other Argentines mentioned by him are David Kohon and his La fecha y un compass (1950); Alberto Fischerman and his film Quema (1962); Narcisa Hirsch and her Come Out (1975); the pioneers of video in the country, Andrés Di Tella, Fabián Hoffman, and Carlos Trilnick; as well as brief references to the artists Marta Minujin and Jaime Davidovich. Our object of attention lies within Machado’s brief survey. Claudio Caldini’s work is contextualized as follows:

Between 1970 and 1983, Caldini produced quite a solid body of audiovisual experimentation, using Super 8 as his gauge and low technology. This body of work is regarded as a bridge between cinema’s past and the electronic present. From the 1990s onward, Caldini adopts video, but always with cinematic insertions, even though his gaze and language remain resolutely contemporary. Among the almost two dozen experimental films shot on Super 8 by Caldini, we can single out Ofrenda (1978), a kind of glittering, multi-hued flower dance with visuals nearing the abstract. It is a wonderful lesson in editing and image-sound synchronization, orchestrated by the Argentinian master of experimental cinema, based on music by Alice Coltrane. (Machado, 2010, p. 35)

Another important reference to Caldini in the realm of experimental cinema studies in Brazil is the catalog for the exhibition Cine sin Limites (2017), curated by Aaron Cutler and Mariana Shellard, precisely focused on the work of Caldini, Narcisa Hirsch, and Jorge Honik. Some of the texts in the catalog are by the artists themselves, offering a precise sense of these filmmakers’ relationship with technique and their commitment to a poetic and profoundly personal vision of cinema.

Both the filmmakers’ and the curators’ texts reveal the story of their trajectories as a collaborative one, a worldview infused with friendship and with aesthetic and thematic affinities. The use of Super 8 at the height of their careers, their taste for travel and for documenting these journeys around the world, and their interest in expanded cinemas from other traditions and cultures are some of the group’s shared points. Yet, it is, above all, the production of aesthetically complex and sophisticated works from immense technical precariousness that draws our attention as a unifying element among the three filmmakers. Presenting a set of Argentine experimental films (some of which were shown in the exhibition), Pablo Marín comments:

[T]he general (shared) context of these films remains inseparable from their fragility of resources. Pretending to ignore that would be a serious error of judgment. But not because it is useful for justifying decisions or final results—quite the opposite. In that sense, the history of these films, most of them shot on reversible Super 8 and 16 mm, is also the history of reduced formats taken to supernatural levels of aesthetic possibility. The economy of resources here is the starting point for an unprecedented formal endeavor. (Marín in Cutler and Shellard, p. 11)

As this essay’s focus, the presence of plants and the plant universe is evidenced in these filmmakers interest in the world’s surroundings, in the outdoors, especially in travel films and in the journeys they each undertake across Argentina and around the globe (Honik is the most “well-traveled” of the three). Among them, it is undoubtedly Caldini who most emphatically carries out this connection with a botanical perspective on the world—which, though not present in all his films, can be found at various crucial points in his work.

Taking a quick tour of his filmography, we can see how Caldini continually provides intriguing glimpses of different aspects of life and art. As a first example, Aspiraciones (1976) is a cinematic meditation that follows, through an intriguing montage whose rhythm is similar to attentive, paced breathing, the image of a candle flame, using a variable-focus lens and metric techniques. As the film advances, images of small plant arrangements are incorporated into its rigorous structure, creating a polyphonic effect that grows increasingly complex.

In surveying the varied set of filmic experiments that explore a relationship with the natural world and with spaces, Cuarteto (1978) is perhaps the closest to our idea of a botanical cinema among Caldini’s oeuvre. Over the course of twenty minutes, the filmmaker presents repetitions and variations of three nature scenes—branches, leaves in the sun, and a red hibiscus. The shots are organized by superimpositions that at first appear random but later reveal a deliberate compositional process: after patiently and contemplatively presenting the three small landscapes, a fourth moment merges them all into a single block, unifying the earlier views and justifying the film’s title with its four distinct segments. Inspired by Chinese philosophy, Caldini ends with a quote from the thinker Chuang-Tzu on the communication of ideas beyond words, signaling a dialogue with nature and the coexistence of human with other life forms.

Vadi Samvadi (1981), meanwhile, highlights a feature frequently revisited throughout Caldini’s work: the exploration of the intersection between Indian music and natural landscapes on a small scale. In this short film, we see the situation and care of plants in a domestic environment; these micro-landscapes are filmed using visual strategies that follow the intensity of the soundtrack, somewhat like a flicker. For its part, La escena circular (1982) captures the silhouette of a couple in front of a window, suggesting a synthesis of cinematic space and the universality of figures outlined against a backdrop of trees and dense vegetation. The camera, isolating specific moments with fade-outs and fade-ins, seems to rediscover cinema as a machine of affective memory.

Another example close to the realm of natural spaces is A través de las ruinas (1982), made during the Falklands War. The camera’s wavering gaze in this film, which wanders through its images in a staggering dance, focuses on dimly lit settings to craft a film shrouded in shadows. Caldini again employs the procedures typical of his other films, achieving new aesthetic effects and different ambient sensations: superimposed images create a dynamic experience of space, forming an apparently continuous transition between one landscape and another; once again, the music references Indian culture and drone elements, though this time with a darker tone than before. It is also worth noting his elegant work with color, as well as the presence of coastal, wintry views that were not apparent in his other films. LUX TAAL (2009) thematizes the passage of time, an important concept in Caldini’s filmography, by depicting the four seasons. The short film broadens its depiction of nature toward a more elemental universe of water and fire, earth and air.

More recently, in one of his few works of the new decade, Poilean (2020) stands out as one of his most radical explorations of the vast world of the small details of nature. Moving through a path that enters a large field of sunflowers, Caldini fully explores the mobility of his camera and the visual possibilities of digital, a format not often used in his career. The camera, recording the minutiae of the setting in extremely close shots, moves directly among the flowers, collides with the petals and leaves, and even with grains of pollen that gather and cling to the plants. The wind and the intense midday light—which reveals grime on the lens—are present at every moment. One might say that the vision in Poilean is haptic—it is as though one is touching each of those flowers, feeling their textures—and, even more boldly, gustatory and olfactory, given that its sensory evocation is so strong it recalls the taste and smell of honey.

And if each of these films in this long career demonstrates a unique dimension of his creativity (which is further emphasized by his involvement with music as an avant-garde composer), Ofrenda is the one that will most powerfully spur us to reflect on his bond with the natural world.

The generous gaze in Ofrenda

Plants seem absent, as though lost in a long, deaf, chemical dream. They don’t have senses, but they are far from being shut in on themselves: no other being adheres to the world that surrounds it more than plants do (Coccia, 2018, p.18)

Perhaps the most delicate film by Caldini, Ofrenda consists of a series of frames depicting a field of white daisies filmed over the course of a single day, its continuous flow weaving a torrent of vibrant images that stimulate retinal persistence. At times, the surface of the screen suggests a floral pattern, reminiscent of a dress or a tablecloth, while also recalling the intricate, kaleidoscopic compositions of American filmmaker and choreographer Busby Berkeley, meticulously arranged in strict patterns of form. Given its brief duration—barely reaching two and a half minutes—it possesses the delicacy of a haiku, seeking to comprehend, in an instant or a sentence, the dimension of time that passes from day to dusk. A soft, atmospheric drone soundtrack evokes the meditative state to which the film invites us, the brief glimpse required for the viewers to immerse themselves in the projection.

Part of a trilogy that also includes the previously described Aspiraciones and Vadi-Samvadi, Ofrenda presents distinctive characteristics, whether in the recurring motifs of natural details, the reflection on the passage of time, the pulsating images that appear and disappear in their own rhythmic flow, or the decisive use of Indian-influenced music. Technically, however, it is an idiosyncratic work of frame-by-frame photography, where different camera adjustments were determined for each capture. When describing his process, the filmmaker emphasizes the careful handling of the camera and the active consideration of choices to be made at the moment of filming.

A succession of points of view and the details of a bush in full bloom are photographed frame by frame: a culminating cycle of daisies. In every shot the position of the camera, the frame, the focal distance and the focus are corrected. The continuity of forms and the relationship between dimensions produces a choreographic illusion. […] With the diaphragm fixed, we continued taking photographs at a regular speed (there are approximately 3,300 frames); the diminishing sunlight results in a slow and prolonged fade-out. (Caldini s/d)

Caldini’s attentive gaze establishes itself between the camera’s eye and its sensible relationship with the world. Central to this argument is the observation that this gaze does not find equivalence in the experience during the film, as seen in Ofrenda: more attuned to the effects of flicker than to the long take, the contemplation offered by this type of cinema is less about the patient scrutiny of the image by the viewer and more about the modernist ideal of pure perception, where the artifice of the filmic medium—achieved through a deep understanding of its mechanisms—takes center stage. If Caldini can reveal the things of the world, it is through the awareness—formally developed in his works—that the photographic representation of nature stages a confrontation between modern devices and other modes of existence that precede all modernity.

The many hours of direct contact between the artist and the daisies take shape in the condensed time of the film’s projection; it is an ecological sensibility almost extinct in Western societal life, which here can radiate through a small crack and reach the cinematic screen—even if only for a moment as fleeting as the few minutes of a short film. Formal strategies employed by Caldini underscore this dual temporality: on one hand, the focused and enduring attitude of the filmmaker in the presence of all that constitutes cinema, whether flowers or cameras, shrubs or lenses; on the other, the temporality absorbed by the aesthetic result, in a very delicate and brief filmic ornament. By questioning the making and the materiality of the work of art as inseparable (Ferro, 2022), it is essential to consider the act of creation as a gesture of generosity toward the materiality of things.

In Ofrenda, the filming methods show an inventive quality that arises from skillful handling of technique. By choosing a single-frame aesthetic—which involves the risks of in-camera editing—and by configuring his device for each new shot, the artist sets himself a challenge that requires a particular mastery of his tools. With artisanal expertise, he becomes immersed in the exercise of finding practical solutions with the instruments of his craft. Reflecting on the category of the craftsman as a human archetype, Richard Sennett identifies a mode of practice that views work not as a means to an end, but as a process that integrates intellect, pleasure, and labor. He describes the craftsman as representing “a special human condition: that of engagement” (Sennett, 2009, p. 30). The generosity of Caldini’s gaze would thus be embedded in the craftsmanship of his approach. Absorbed in a single activity throughout an entire day, he devoted himself to the focused observation of nature and to inventive play with the cinematic apparatus.

Making a film is the filmmaker’s act of love toward the world, manifested on two levels—an openness to sensations and a tactile handling of the apparatus. Building on this understanding, Sennett considers the craftsman’s condition of engagement as inseparable from the material curiosity he devotes to the tools at his disposal. Cinematic craftsmanship implies an approach that prioritizes the agency of the tools of the trade, involving an activity of human discovery through the use of the machine. The camera, with all its potential uses, would be, in these terms, a “stimulating tool” (ibid., p. 217), challenging its operators to expand their skills, uncover the secrets of a technical object, and refine their understanding of their own craft. This is one of the strengths of this type of experimental cinema, which finds in cheaper technology an opening for the highest degree of formal sophistication.

The camera is, evidently, the pathway to the generous gaze that Caldini directs toward the world. It is through its operation that the visual material is recorded, and it is through this machine that aesthetic enjoyment is affirmed and the making of a film truly materializes. Ofrenda stands out for its use of the camera as an almost analytical instrument, probing the imperceptible changes in the environment that escape human observation—changes that only the camera could concretely capture. Vision here should be understood as both an active gesture and a playful experience: if there is something truly rigorous in the process described by the filmmaker, it stems from a rigor interwoven with the childlike contemplation of nature’s states, evoking the first sensations of early childhood.

In this sense, it is light, just like the flowers, that is a primordial event in the short film. The variations in luminosity draw the narrative arc of the passage of time: what begins with a shiny representation of white petals of the daisies gradually changes, reaching its climax in the reflection of the last golden ray of sunlight of the day, and ends with the disappearance of the flowers, which become bluish stains dissipating into the dark background. This attention to light is what places the work within the realm of a study that questions the world, time, and space, observing the movement of nature in a small piece of existence. As in the early attempts with the cinematograph and alternative photographic techniques mentioned at the beginning of the article, there is a tangential connection to the scientific perspective, but one that has its aesthetic intentions even more emphasized by positioning itself within the realm of art.

Thematization of light evokes the connections between cinema and painting. Jacques Aumont (2004) initially points out the ontological difference between both mediums: the pictorial approach to light representation using a raw material such as paint; light, in film, is an inscribed and inevitable factor. The work with light in a film is almost always aimed at controlling its effects, with the history of cinema full of obvious examples (Orson Welles, Josef von Sternberg, Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau). As Aumont states, “[i]t is in its relationship with light that the plastic paradox of cinema is best perceived: a victim of its technical nature, it captures light too well, effortlessly, to know, from the outset, how to work with it.” (Aumont, 2004, pp. 179-181)

However, Caldini is not interested in controlling light. More than that, the fixed aperture configuration would take the opposite route: it would not be an attempt to control the results but a conscious gesture of investigation on how the medium responds to light. The effects of this endeavor could not be measured by the ability to forge the ideal light in a studio or location, but by engaging in a duel between technological expertise—material knowledge attuned to film properties—and the components of the real—sunlight as raw material for a filmic craft. Other modifications, regarding focus or focal length, are still simple adjustments, but they reflect handcrafted attention and meticulousness in how to utilize cinema.

At the center of this technique is the choice for a single-frame aesthetic that invites the spectator to acknowledge this slow progression as a discontinuous process: “We were not trying to recreate movement, but rather to stop it, to produce static continuity between what were, themselves, different shots.” (Caldini, s/d). Also in his research on the secret kinship between painting and film, Aumont theorizes on the temporality of each medium, commenting on painting series and the passage from one moment to another in artistic reception. A series, broadly speaking, is the creation of several images of the same subject given at distinct moments, with Claude Monet’s Rouen Cathedrals (1892-1894) being a classic example. According to the author, Monet painted the same cathedral under different lighting conditions— a key subject of Impressionist research. The most elementary aspect of Ofrenda—capturing the light when it strikes—resonates clearly, as the first connection between both.

What makes the series a model for thinking about cinema, and especially about the time woven by film editing, is the understanding that the succession of two images can unlock the gears of a micronarrative. The effect of difference, which is certainly a cognitive effect of reception, turns the series into a type of collection attentive to the sharp jumps between two moments, between two images. It is the reconstruction of a totality, in its temporal aspect, that is only present as the consciousness of a missing part; that is, as an interval, as a distance. This is what Aumont skillfully adds: “In the confrontation between two views, at once similar and different, the eye gains, in effect, a new possibility: that of finding itself between the two, where there is nothing, nothing visible.” (Aumont, 2004, p. 97).

By rethinking the notion of the cinematic shot, Ofrenda and the “static continuity” that its creator speaks of seem to strictly follow the principle of discontinuity that Aumont perceives in the series. However, cinematic construction generates a visual disturbance even stronger than that of the series due to its extensive nature, its one-directional unfolding over time. The frenetic effect of the 3,300 still images in Ofrenda is an optical illusion in which choreography is created by the shock between one frame and another, which the eye processes continuously. The film spectator is, thus, conditioned by the temporal sequencing of the images that were previously designed by the filmmaker. Another question lies in the temporal dimension, one that separates the series from cinema through a technical specificity inherent to the making of each work. If, by analogy, one painting in the series represents a still frame in the film, the production in each differs drastically. For Monet, an entire day is needed to produce a single part of the work, the same day in which Caldini will complete nearly 3,300 images of his film.

However, even though Ofrenda’sformal elements seem to radicalize and add nuance to this precedence of cinema over the series, there is still the paradox of a fleeting examination of space that connects Caldini and the Impressionist modus operandi. Monet’s cathedrals are grouped together in order to make the proximities and distances between multiple moments visible. In this cognition process, the tonalities of the paintings gain prominence, and the meteorological particularities of each day depicted are crucial aspects for articulating the body of the collection. Caldini’s film similarly attends to the surroundings; in both cases, the work of perception focuses on different atmospheres, the possible ambiences of a particular place, and demands from the eye a mobility that crosses the discontinuity between them.

The gaze upon plants, better than the architectural theme, accentuates this notion of grasping the world in constant mutation, especially when the analysis of film aesthetics intersects with the aforementioned philosophy of plants by Emanuele Coccia (2018), in which observing plants is to come into contact with a particular notion of being-in-the-world. It thus draws a parallel with another of Monet’s series, his famous work with the water lilies from the garden at Giverny. In all three cases, in the series and in the film, we are focused on the sensible life as developed, also, by Coccia:

The obvious distance that separates humans from other living beings does not, in fact, coincide with the abyss dividing sensibility from intellect, the image from the concept. It is expressed entirely in the intensity of sensation and experience, in the strength and efficacy of the relationship with the world of images. An irrefutable proof of this is the fact that a great part of the phenomena we call spiritual (be it dreams or fashion, language or art) not only presupposes some form of relationship with the sensible but is also possible solely thanks to the ability to produce images or to be affected by them. (Coccia, 2010, p. 11)

In Coccia’s sense, an image would not only be one manufactured by humans and inscribed in the artistic fields, but the entire substance of the world that provokes our sensibilities—plants and sunlight, but also water, wind, and even fauna. What the previous quote questions is the idea of the sensible as an inherent property of being-in-the-world, with humans benefiting from a deepening of these sensitive faculties. This analysis of Ofrendasought a path that interpreted it as the result of mediation between the filmmaker, his tools, and the images of a sensible life. Humans, through art, can create other forms of the sensible and delight in the revelation of existence through artistic means. The gaze of Caldini’s cinema is the active exercise of the hunger for the world that our brief stay in it makes us feel, with the artist being the one who offers us new possibilities of encounter.

Cosmic ornaments, small infinities. Notes on vegetal cinema

Our essay initially aimed to highlight the central place of the world of plants in a tradition distinct from narrative cinema. The species of flora, in their “passive” reality that is opened to contemplation, characterized themselves as indispensable objects of study in the scientific use of moving images. The invisible string between these practices and the most sophisticated experimental cinema is made explicit precisely through aesthetic correspondences that connect the rigor of scientific observation with the free gaze of artistic fruition. These characteristics are amplified in the perception that Ofrenda offers us, unveiling the vast universe contained within the modest formation of a shrub adorned with daisies.

The relationship between cinema and the natural world reveals itself to be a fertile field of investigation, as vibrant and essential as its equally rich and diverse representations of fauna. Therefore, what we have crafted throughout this text can be described as a cinematic herbarium: a small collection of vegetal samples arranged to be showcased as an extension of the world in images—a collection that does not find closure here, always leaving room for further additions, for new perspectives directed toward the world.

References

Aumont, J. (2004). O olho interminável: pintura e cinema. São Paulo: Editora Cosac & Naify.

Beauvais, Y. (n.d.). Rose Lowder: Bouquets d’images. Re:Voir. Retrieved September 17, 2023, from https://re-voir.com/shop/en/rose-lowder/205-rose-lowder-bouquet-d-images.html

Caldini, C. (n.d.). Ofrenda. Light Cone. Retrieved September 17, 2023, from https://lightcone.org/en/film-1985-ofrenda

Coccia, E. (2018). A vida das plantas: Uma metafísica da mistura. Florianópolis: Cultura e Barbárie.

Coccia, E. (2010). A vida sensível. Florianópolis: Cultura e Barbárie.

Cutler, A., & Shellard, M. (2017). Cine sin límites: Claudio Caldini, Jorge Honik e Narcisa Hirsch. São Paulo: Centro Cultural São Paulo. Retrieved September 23, 2023, from https://www.mutualfilms.com/Livro1Web.pdf

Dallas, P. (2014). Into the woods: Director Michelangelo Frammartino talks about his mesmerizing installation work Alberi. Filmmaker Magazine. Retrieved September 17, 2023, from https://filmmakermagazine.com/83356-into-the-woods-director-michelangelo-frammartino-talks-about-his-mesmerizing-installation-work-alberi/

Dargis, M. (2016, April 1). Bruce Baillie, a film-poet collapsing inner and outer space. The New York Times. Retrieved September 17, 2023, from https://www.nytimes.com/2016/04/03/movies/bruce-baillie-a-film-poet-collapsing-inner-and-outer-space.html

Dixon, B. (n.d.). Frank Percy Smith. BFI Screenonline. Retrieved September 17, 2023, from http://www.screenonline.org.uk/people/id/594315/index.html

Ferro, S. (2022). Artes plásticas e trabalho livre II: De Manet ao Cubismo Analítico. São Paulo: Editora 34.

Foery, R. (n.d.). Fogline. Light Cone. Retrieved September 17, 2023, from https://lightcone.org/en/film-6759-fog-line

Hammerton, J. (n.d.). The Birth of a Flower. BFI Screenonline. Retrieved September 16, 2023, from http://www.screenonline.org.uk/film/id/594372/index.html

Machado, A. (2010). Pioneiros do vídeo e do cinema experimental na América Latina. Significação, 33, 21-40.

Melo, P. A. S. B. de. (2022). Found foliage: Impressões botânicas no cinema experimental. Recife: PPGCOM-UFPE.

Sennett, R. (2009). O artifice. Rio de Janeiro: Record.

Vieira, P. I. L. (2022). Animist phytofilm: Plants in Amazonian Indigenous filmmaking. Philosophies, 7(6). https://doi.org/10.3390/philosophies7060138

*

Angela Prysthon is a Full Professor at Universidade Federal de Pernambuco, Brazil. She is the author of, among others, the books Cosmopolitismos periféricos (2002), Utopias da frivolidade (2014), Retratos das margens (2022), and Recortes do mundo (2023). Her writings on cinema, cities, landscapes, media, and literature have appeared in books and journals such as Culture of the Cities (2010), Visualidades hoje (2013), Devires, La furia umana, and Contracampo.

Lucca Nicoleli Adrião is a curator and researcher at the Federal University of Pernambuco. He is currently a master’s student in the Graduate Program in Communication at the same institution (PPGCOM-UFPE), focusing on studies on avant-garde film practices.

To cite this article: Prysthon, Angela and Nicoleli, Lucca (2025) Botanical Offerings, Plants as Gifts, Experimental Cinema and the World of Claudio Caldini, La Furia Umana, 46. https://www.lafuriaumana.com/angela-prysthon-lucca-nicoleli-botanical-offerings-plants-as-gifts-experimental-cinema-and-the-world-of-claudio-caldini/

Keywords:

Download PDF

- A previous version of this essay was published in Portuguese in https://periodicos.ufpa.br/index.php/ppgartes/article/view/16888 ↩︎