Invoking la Malinche is the best way to speak of the end.

Franco “Bifo” Berardi

The image above, (fig.1) an oil painting by Mexican painter Antonio Ruiz “el Corcito,” from 1939, shows an indigenous woman lying in an voluptuous bed of blankets, from which a Spanish colonial city erupts tremulously in the slopes of a mountain. The painting El sueño de la Malinche (Malinche’s dream) depicts the realization of the intuitive prowess and predictions of Malinalli, also called Malinche, the Nahua lover of Capitán Hernán Cortés, conquistador of Mexico, and the mother of the first mestizo of the Americas. Malinche was able to predict and sense the end of her world, the world of Mexicas and Aztecs and the birth of another world, the world of the Spanish conquest. In Franco “Bifo” Berardi’s words: “Humans have already experienced an end of the world, or the end of a world. A world ends when signs proceeding from the semiotic meta-machine grow undecipherable for a cultural community that perceives itself as a world.” (:331) This unity of patterns and experiences that form a world is fragmented, and draws near an end when all meanings stop resonating and seem to have no projection into the future. When a world ends, nothing seems to function the way a human conglomerate expects, because rules, patterns and normatives have changed. If that world is to survive it needs to accommodate, reform, exchange and grow into another skin. Malinche was the translator and lover of Hernán Cortés. She was the daughter of a Nahua nobleman who died; as a consequence her mother remarried and Malinalli was given as a slave to traders. Afterwards she would be offered to Cortés as an interpreter. In her book Malinche Laura Esquivel writes about the world of that child who had to bear the dawn of her civilization. Esquivel imagines Malinche in her poetic demisse from being a happy little girl to becoming the lover of one of the most violent men in the conquest of the New World. Very smart and with a gift for languages, she aptly learned different dialects like Aztec and Maya; when the Spaniards arrived she was already proficient in various dialects of the zone. It was not difficult for her to learn Spanish for she also had great sensibility to perceive the essence of what was being said. In translating the tongues of the Maya and the Aztecs, Malinalli translated the spirit of her own culture. Translating from Spanish to Maya, Aztec and Nahua, conversely, she translated a foreing world of which only the speech (language) was available to her. For her ability to swiftly traverse between worlds, generations of Mexicans have called her “La Chingada” (the raped one) and accused her of treason.[1] Octavio Paz in his essay “Los hijos de la Malinche” (Sons of Malinche) writes:

The symbol of surrender is doña Malinche, Cortes’ lover. True, she gives herself to the lover, but he discards her as soon as she is not useful anymore. Doña Marina turns into a figure that represents indigenous women, fascinated, raped or seduced by the Spaniards. (:1)

The Mexican mestizo according to Octavio Paz is ashamed to be the product of rape, and in a sad reversal of fortune instead of siding with the victim, the raped mother, he sides with the conqueror, the father. For this mestizo La Malinche, the translator, is a double traitor: “Not only did she betray her own people, creating a link with the invaders, but she also betrayed her lover himself.” (:335) writes Berardi. But he also points out that she did not technically betrayed her own people, since she had been sold to slavery in the first place.

There is another interpretation of the role of the Malinche, and it comes from “Las Nietas de la Malinche” the granddaughters of the Malinche, feminist scholars who do not see Malinalli’s mediation as betrayal at all, but a positioning of herself as someone who was able to see beyond what she was permitted to see. As a mediator Malinche is the seed of the new world opening up, the plant grown out of the sprouting of the fertile soil of Aztecs and Mayans. Malinalli is represented by corn, the ultimate food of the new world, the golden fruit that accompanied her everywhere. Esquivel writes that the night before she was going to be given away she worried: “What would become of my cornfield?” (:21) as she carried the corn seeds with her. Some of these seeds not only grew into crops that fed people all over the world, but also into the voices of the Chicana movement, a double meaning for the migration of those seeds into new lands. As Marta Lamas writes in her essay on Paz’s “El Laberinto de la Soledad”: “La Malinche has metis (the cunningness of the weak confronting the strong) in forming an alliance with the spaniards she seduces Cortes and influences him beyond being his translator, Malintzin is being faithful to herself, to her own desire.” (:1) Lamas argues that Octavio Paz is unable to see Malinche as a woman who is able to desire and have agency. He personifies her as the slave who was victim of men first and then went from one to another peddling sex and support. He doesn’t see her for what she truly stands for, thus, ends up reifying the patriarchal myth of the oppressed without desire and agency.

Malinche is not only an expression of mestizaje, but of the vision she herself opened, as a seed of corn, of the rebirth of a coming-world from the ashes of the old. As mediator she not only translated one language to another, her own culture to the Spaniards and vice versa, she was also able to foresee the plant, the leafy stalk of maize in the tiny kernel of the corn she held in her sweaty palms. In Berardi’s parlance: “But foremost, she is the expression of the consciousness that her world is over: she knows that her world as a system of consistent cultural and semiotic references has disintegrated.” (:335) Disintegration does not mean the end, the kernel that is the seed of maize disintegrates in the soil before sprouting into the October rains as a lean grass. “Only when one is able to see collapse as the obliteration of memory, identity, and as the end of a world can a new world be imagined”, and Berardi continues: “This is the lesson we must learn from Malinche.” (:335) As a mediator she epitomizes the role of the contemporary artist, a translator between worlds, a becoming-Malinche in the broad meaning of the deleuzian term. In the words of Deleuze and Guattari women are the essence of becoming, a man first has to become-woman in order to exert any becoming at all. This way of becoming-woman is something of this nature: “There are women on the other hand,” they write, “who tell everything, sometimes in appalling technical detail, but one knows no more at the end than at the beginning; they have hidden everything by celerity, by limpidity. They have no secret because they have become a secret themselves.” (:289) Thus, becoming-Malinche is to possess all the secrets by being the secret itself. To possess in itself the future is what a seed does, the tiny volatile seed of maize is already a plant, bread and meal, it is the secret itself; when Malinalli preserves those little seeds, she preserves the harvest. She carried the old world into the new one.

Running now is the second year of pandemic times. 2022 is the year in which we assess the new world that is coming to upend the old one. Berardi notes: “The bio-info automaton takes shape at the point of connection between electronic machines, digital languages, and minds formatted in ways that comply with their codes.” (:336) We have been inoculated with a vaccine that is supposed to prevent us from being infected with the deadly coronavirus, but others predict it is a bio-info that will change us completely. Thousands of people protest what they see as the inevitable mark of those who comply with the codes: the sign of evil, the vaccine. Apocalyptic images abound, religious cults and agnostic groups alike predict the end of times. There is also a tint of sublime-mongering in the predictions of these groups. According to Achile Mbembe:

The general atmosphere of fear also feeds on the idea that the end of humanity —and thus of the world –– is near. Now, the end of humanity does not necessarily imply that of the world. The history of the world and the history of humanity, although entangled, will not necessarily have a simultaneous end. The end of humans will not necessarily lead to the world’s end. By contrast, the material world’s end will undoubtedly entail that of humans. (:32)

Thus, if humanity ends, the planet will continue to live its cycles, seasons will come and go, the tremendous force of phusis will overtake every single edification and man-made contraption. However, this will not happen just yet. Human beings are still alive and promising to stay along with the latest technologies; the “automaton’s flow of enunciation” in Berardi’s words, will keep creating a world incompatible with “five centuries of humanism, enlightenment thought, and socialism.” (:336) Plus viruses, love, compassion and laughter. This new world we are stepping into is clearly able to model itself according to our voices, desires and yet unacknowledged whims. However, if we are to become-Malinche we need to be able to betray our old world and the coming one too. Will the artist become-Malinche first of all? Maybe so; there is already a sense of permeability in artists that is susceptible to plant contagion by nearness. Plant ontology, or the notion that plants do have personhood, gives plants a perspective of their own; in indigenous communities across the Americas it is said that plants can be heard and apprehended by just being close to them. No machinery or contraptions are necessary, we possess in our bodies the technology we need to perform this task. “But the unbridgeable difference” writes Berardi, “between the conscious organism and the automaton––as complex and refined as it may be––lies in the unconscious.” (:337) Where is this unconscious that has not been contaminated with bio-info? Most probably in dreams and desire. The dream of Malinche in Antonio Ruiz’s painting draws a bridge towards a new world. Although her dream seems to be confined to a dreadful room where a world seems to have ended, the new one appears to have been constructed right over her own body. Malinche walks towards this new reality with the fear of a nightmare unfolding. It is in this unconscious state where she is able to foretell a beginning of that specter of a world. Gloria Anzaldúa’s poem and blessing acknowledges La Llorona, La Chingada, and Guadalupe, as “the madres” of Chicana writers and activists:

Moving sunwise you turn to the south:

Fuego, inspire and energize us to do the necessary work,

and to honor it

As we walk through the flames of transformation.

May we seize the arrogance to create

outrageously

soñar wildly—for the world becomes as

we dream it. (:157)

Anzaldúa asks the mothers, the Malinches, those who dare to envision, to give her clarity and strength to dream of another world. Is it not then that our worlds are ending all the time? Is it not that we reinvent and recreate these worlds, metamorphosing ourselves again and again? In the Popol Vuh, men and women’s creation took place every other day.[2] Our world, the Anthropocene that is, seems to have lasted a long time, the time it took us to extinguish various species, discover many others as some vanished under our eyes, turn the earth upside down to extract all kinds of minerals and precious stones from her, and become a super inhabitant of the infosphere, cohabiting a world with automatons and computerized realities. Our unconscious lives, nonetheless, within that veiled spirit or soul, within dark night adventures we call dreams: the voices we hear, and that psychiatry has pathologized into diverse maladies. The unconscious is what changes with trauma, addiction, habit and grace. Invariably there will be the announcers of the end from every religion prompting their subjects to repent and embrace the new era. If humans just saw ourselves as any other creature of the universe, we could realize there is no end nor beginning. We will metamorphose into compost, butterfly, sap, flower or seed. The seed will produce other beings, just beings in the presence of fires, earthquakes, landslides and heavy flooding. None of that was dedicated to us in particular. Earth continues her voyage across the firmament and around the sun.

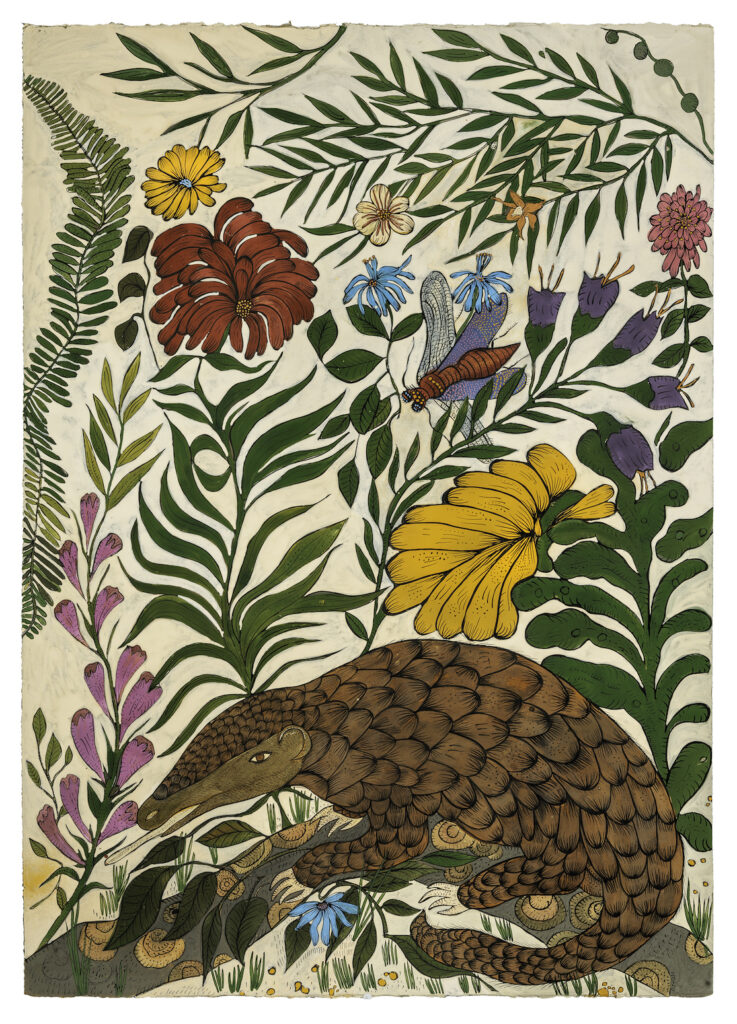

Mapping the soil in such dangerous times equals planting, caring for a seed, hiding it like Malinalli kept hers, until she found a fertile soil in which to plant. Grieving is part of this process, staying with the trouble, not flying away to another planet, but working to fix this one. The entanglements of such times prompt humanity in a different and more mature way. Paraphrasing Anna Tsing’s words, Donna Haraway writes: “to living and dying with response-ability in unexpected company.” (:38) Thus, the bat, the pangolin and the different bacterias and viruses that inhabit us humans invite infection and contagion in the most interesting levels, not exempt from grief, nevertheless sobering. Better said in Haraway’s words:

Grief is a path to understanding entangled shared living and dying; human beings must grieve with, because we are in and of this fabric of undoing. Without sustained remembrance, we cannot learn to live with ghosts and so cannot think. Like the crows and with the crows, living and dead ‘we are at stake in each other’s company. (:39)

When one world ends the grieving is devastating, examples abound: the California fires, Hurricanes Katrina, Marina and Ovidio in the Eastern United States, the mud slides of Sobradinho and Petrópolis in Brazil, La Gasca in Ecuador, just to count some of the disasters our ending world is experiencing. Going back to how things were doesn’t quite work. It would be equal to forgetting, which means an absence of thinking. Staying with the trouble means to dwell and linger in the grieving moment, living with ghosts, elucidating a different way of living and translating ourselves into the future.

Pangolin and imaginary habitat. Ana Fernández / Miranda Texidor. Gouache on paper2021. Photo Christoph Hirtz. © The artist.

Ana Fernández

[1] Octavio Paz’ entire essay is called “Los Hijos de la Chingada” and is part of Chapter 4 in El Laberinto de la Soledad.

[2] “Then there was the creation and formation. From earth, from mud they made the flesh of man.” (Ivanoff: 27)

Bibliography

Anzaldúa, Gloria E. Light in the Dark, Luz en lo Oscuro. Edited by Analouise Keating. Duke University Press, 2015.

Berardi, Franco “Bifo”. AND, phenomenology of the End. Sensibility and Connective Mutation. Semiotext(e). The MIT Press, Cambridge Mass, 2015.

Deleuze, Gilles and Felix Guattari. A Thousand Plateaus, Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Trans. Brian Masumi. University of Minnesota Press, 1987.

Esquivel, Laura. Malinche. Trans. Ernesto Mestre-Reed. Washington Square Press, New York, NY 2006.

Haraway, Donna J. Staying with the Trouble, Making Kin in the Chtulucene. Duke University Press. Durham and London, 2016.

Ivanoff, Pierre. Civilizaciones Maya y Azteca. “Popol Vuh” Mas-Ivars Editores. 1972

Lamas, Marta. “Las nietas de la Malinche”. Una lectura feminista de ‘El Laberinto de La Soledad’”. Zona Octavio Paz. https://zonaoctaviopaz.com/detalle_conversacion/334/las-nietas-de-la-malinche-una-lectura-feminista-de-el-laberinto-de-la-soledad#

Mbembe, Achille. Necropolitics. Trans. Steve Corcoran. Duke University Press. Durham and London 2019.

Paz, Octavio “Los hijos de la Malinche”, en El laberinto de la soledad. Ciudad de México: Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1951.