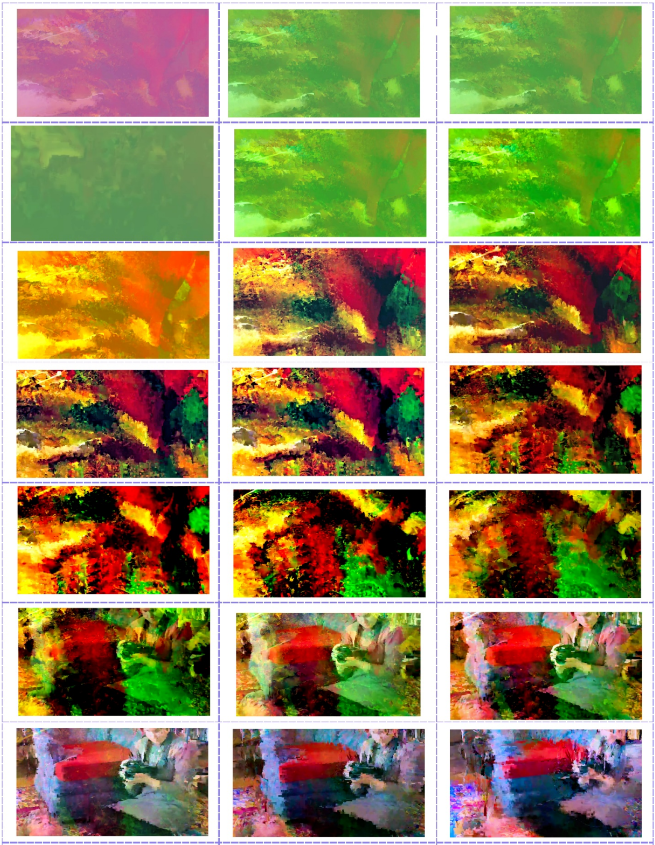

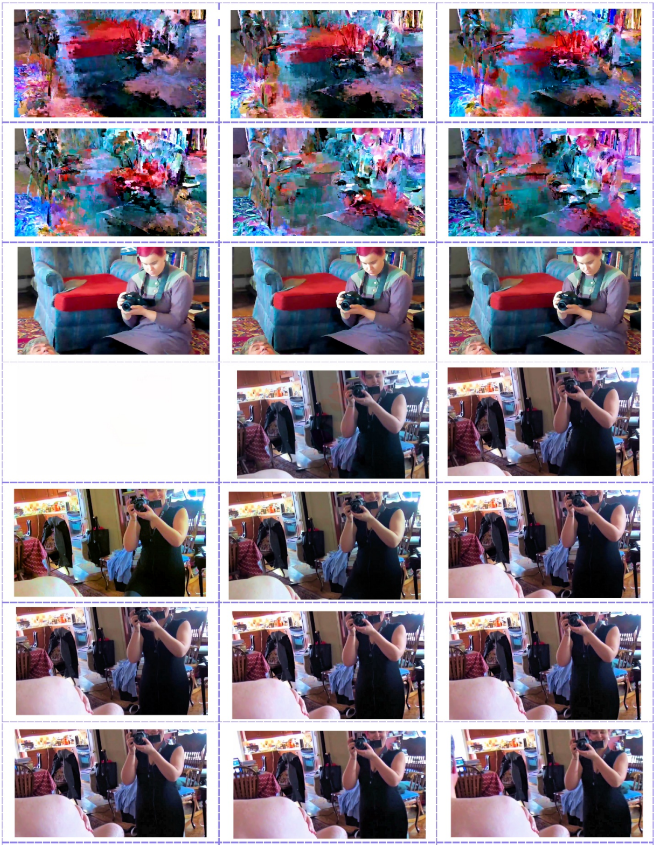

Including commentary on and images from Alone (All Flesh Shall See It Together), a digital work by R. Bruce Elder and Ajla Odobašić

Learning From My Women Students

This is the third of three linked essays whose purpose is to triangulate ideas from Plotinus’s aesthetic built on a feeling of love for higher reality (and the analogy between aesthetic experience and henosis, the unification of One that is beyond being), the cosmology in which Alfred North Whitehead unfolded the metaphysical implications of the science of electromagnetism, and feminist art and the experience of parler femme. In the previous installment I outlined how it came to pass that the courses I was most strongly identified with for the last three decades of my teaching in an art school were courses in which women students almost exclusively enrolled, and in which the participants in class mounted nude performances, usually improvisatory group performances that were deeply influenced by contact improvisation. There I suggested, in sum, that the experience led them to archaic forms of experience of the sort that the psychoanalyst and theorist of language Luce Irigaray described in her writings on phallogocentrism. (1)

Phallogocentrism inhibits the development and circulation of a distinctive women’s voice by positioning women as support for men’s projects, available to be governed and regulated by men, and submissive to men’s authority. Phallogocentrism is based on a form of ego psychology that proposes a unified self, a (fictional/identificatory) self that comes into being by becoming free of the other / others. Phallogocentrism strives for a fixed and pre-determined being. A woman’s role in this is to serve as a sort of mirror that supports men’s projects, thus helping to foster male identity and to give shape to men’s drive for mastery. In the absence of men, a different provisional self, a self that is always in process, could emerge out of the relationships among women. The self-in-relation was paramount. These all-women collective nude performances bolstered a different sense of the self than as support for male autonomy. They understood in their flesh that the members of the collective were actively engaged with one another and that what they created collaboratively allowed each and all to achieve a provisional self-realization through their relationships to one another. These performances arose out of the experiences of the women themselves; the absence of men reduced the regulatory effect of the masculine languages of art and the pressures women feel to serve as alter egos for men—for men’s ways of speaking, thinking, and making. These all-women performances intensified the experiences the women had of one another and engendered what could properly be called an erotic connection among them; a feminine jouissance fostered a distinctive, relational feminine subjectivity. That these were all-women performances freed the women’s subjectivity from the imperative to be the internalized mirror of the male, the (supposed) female ἀρχή (arkhé, origin or source of action) for the male, from whom men seek approval and, in seeking their approval, convert women into props for male autonomy and male mastery: the transition from infancy to adulthood for men is from first receiving physical shelter to later receiving psychological shelter from women. One result of this male-centred anaclitic process is a truncation woman’s being, as women become defined as being a support for another. By forging a society of women and by intensifying and eroticizing their relationships, these performances helped the participants to recognize, through movement and touch, that neither personal nor sexual identity is a matter of fixed and pre-determined being, of underlying essences or common properties; rather they are forms of becoming—of provisional self-generation. Gesture, touch, flesh, and being-on-the-way are hallmarks of women’s writing and, it seems, more generally, of women’s making.

If phallogocentrism concerns the complicity of language with law (a complicity made possible by the gap between Symbolic and the Imaginary orders), these performances, by re-connecting actions to drives and to the pre-Symbolic order, helped forge a distinct form of thinking and working, and a different kind of society than that based in the Symbolic. The male identification with a (fictional) unified self is only made possible by the sacrifice (through repression) of a primary connection; patriarchal society encourages the female become a mirror of this sacrifice. It could go without saying that in late modernity the sacrifice of memory, connection, and tradition has reached an unprecedented brutality—this will lead either to the complete collapse of civilization foreshadowed by the horrendous intercivilizational brutality we are witnessing or to a renewal of the sort Kenneth Rexroth called for and I have been reflecting on in this essay: the revolution—for it truly is that—world-wide renewal that arises from an archaic feminine.

We are at the cusp of a revolutionary spiritual renewal or catastrophe. The women in these classes were exhilarated at becoming a part of an antithetical subjectivity (antithetical in the sense that it did not revile women’s bodies, as patriarchy does)—an antithetical subjectivity that asserts itself not against the body or at the expense of the body (that is, a subjectivity that might have evolved at the cost of renouncing the body’s embeddedness in archaic feeling or its memories of coming-to-be), but through the body and its fluxing energies. More exactly, they experienced the joy and terror of a metaphysical abyss, of a freedom whose ends must be devised without help—because they eschewed pre-formed, conventional/societal/masculinist images of women’s being and women’s pleasure and were required, by the originality of what they were doing, to do without concepts handed down from precursors. They accepted the creative risk of becoming, of experiencing oneself as relational, as a self-in-process simultaneously emerging from and merging into a community mutually involved in self-creation.

The participants in these class projects stated with no little enthusiasm that they found the work liberating: they experienced an intense form of sharing and collaboration. They were struck with the process-orientation of the collaboration: as far as the actual performance was concerned, they got together and created in real time a novel and unrepeatable event. For them, the spiritual benefit experienced in the time-limited process of collaborative co-creation surpassed the aesthetic value produced by traditional means of artmaking that, ironically, explicitly strove to evoke a sense of timelessness—I characterize as ironic because the spiritual value experienced in the real-time process of collaborative co-creation provided unsought something akin to intimations of the timeless transcendent that traditional artistic means consciously sought but so often failed to achieve. Over the many years this course was offered, students continued to voice enthusiastically the feeling that nude collective performance granted revelations about the self that emerged in the process of showing/giving oneself to another/others and about being together. They came to feel viscerally that body-selves rely on being looked at by others to realize themselves and to flourish, and they felt viscerally, in their naked state, how each body craved the regard of the other and remade itself to solicit that attention. They also came to feel strongly that others’ desires mirrored their own. In other words, they came to feel, in their flesh, that each belonged to all others.

Diaries these student performers kept reveal that these spontaneously improvised performances allowed them to experience a new society, a community of love, emerging through connection, and to experience their provisional self-generation as occurring in relation to this process. Engaging in a form of spontaneous co-creation that bypassed immediate rationalization, they were bringing forth, pro tempore, a feminine language of kinaesthetic sensation, of movement and touch, of gesture and rhythm and repetition (a form of parler femme) that, as Luce Irigaray pointed out, is not only a threat to patriarchal culture but also a medium through which women may be creative in new ways. They were discovering a form of expression that would bring into existence alternative forms of relationship, perception, and expression and new forms of exchange through which each would intensify all others. They were generating a mixture of discourses that produced a novel intercorporeal subjectivity—they were experimenting in creating a novel micro-politics of community and a parler femme that functioned as a counter-molecular line of flight. The dynamic and improvisatory nature of their collaboration generated forms that, unlike those of men’s art, were not teleologically or narratively focalized. Instead, they were repetitive, cyclical, adventurous, meandering, unpredictable, always underway, and always without a destination. Among the revolutionary features these performances shared with other examples of radical women’s art was the effacement of the traditional divide between theory and practice. However, the thoughts—the “discourses”—the performances generated were not phallogocentrically aimed at outcomes. To the contrary, the thoughts they generated moved through and over the entire body as they sought expression—expression pro tempore.

Applying what I learned to my own work

As I noted in the previous installment, photographing a nude (of whatever gender) provides an opportunity to “do gender.” When I began making films, I recognized that heretofore my female co-workers weren’t being given the same opportunity to do gender and make culture, to create pictures that reflect or express who they were, to use the nude images (of whatever gender) as a means of personal self-expression: indeed, I brought this conviction with me to filmmaking. Furthermore, in the culture at large, women had few to no opportunities to view pictures of nude males other than musclebound hulks, images altogether lacking in tenderness. More to the point, women were rarely actual producers of images of nudes: when it came to images of nudes, the artworld preferred they not be makers but models. The artworld’s reduction of female experience, my co-workers and I felt, was an inequity that should be combatted.

As I outline below, the subject of the gaze (le regard) is not a passive subject—and this is acutely true being a cinematographer’s model. That role involves soliciting attention, receiving it with gratitude, and responding to it with an active understanding that one tries to convey to the other. Yet there are almost no precedents for female cinematographers/filmmakers to experience such behaviours from nude male models (in fact, I can think of none): to be dependent on the regard of another is believed to be incompatible with being a real man. What is more, as far as I know, there are no precedents or parallels for a female cinematographer and a nude male model understanding the process of making nude images together as a collaboration. But that was exactly how my female co-workers and I have understood the work we did together—it has been a collaboration that, so far as I know, is without precedent or parallel, certainly in extent, and I hope in the depth of its implications for new forms in cinéma féminin.

In what follows I outline my experiences as a nude model for my female co-workers and a kind of co-presence, that is to say, a novel intercorporeal subjectivity that came about as a result of giving myself to a process that would allow archaic feelings and memories of coming-to-be to emerge entre-nous; this occurred by encouraging the body’s fluxing energies to re-connect its actions to drives and to the pre-Symbolic order, thus forging a distinct form of thinking and working that accepts the creative risk of becoming, of experiencing oneself as relational, as a self-in-process simultaneously emerging from and merging into a community mutually involved in self-creation. The process demanded I refuse the singularity of isolated, dominating being and to risk feeling, viscerally, in my naked state, that my body craves the regard of the other and remakes, over and over again, itself—it demanded I solicit another’s attention in order to feel, in my naked flesh, that my new being belonged as much to my co-worker who filmed me as to myself. It demanded that I sense that, in Irigaray’s sense, I was becoming woman, since I understood that my new flesh was entre-nous.

Here are my phenomenological reflections on the process.

Becoming Woman: New Flesh, New Life, Entre-nous

For examples of electric images—feminine ecopoetic images—by volunteering to be a nude model for women artists with whom I collaborated, see Appendix, Part 2

The most important thing for me now is that you are seeing me and that I can perceive you seeing me. I am stirred by the thought that, just as I can perceive what is invisible in you, you can perceive what is invisible in me. The dissappropriation I experience in this somewhat awkward state engenders an apperception that is fused completely to perception: I am aware I am the subject who is looking at you looking at me and my awareness that you are exploring me as intimately as you are has the effect of attuning me all the more sharply to the electric vibration in my new flesh. I no longer know you as simply just another person I encounter in the world, more familiar to me, perhaps, than many (and so more accessible to my understanding), but still one amongst all the many others I meet in my workaday world. That sundered world of glancing awareness of many quasi-anonymous bodies-with-consciousnesses has gone. In this new world that has developed between us, my awareness of you is a focalized awareness: I experience you as a point of intense sensory awareness and I experience myself as a subject-for-you-as-a-subject-exploring-me. I don’t at all feel reduced to object, as one common misunderstanding represents what we are doing here: rarely do I feel so strongly that I can see through another person’s body to see what is invisible in her—and what I perceive in that invisibility is her attention to what is invisible to me. It is an almost magical crossing of feelings and awareness, yours and mine, elevated to a Beyond-Self.

I lie here, naked, agreeing to do what you ask. When you ask, I notice you speak more in verbs and participles than in nouns and gerunds. Nothing here is reified, I conjecture. We are building a world that will enclose us, whose limits will be defined by the scope of your attention and my eagerness to fill it. Everything is in process here, everything undergoes change. Nothing in this world has the nature of an object isolated in a bounded space. Desire makes this world, and desire is endlessly protean. As we pass from moment to moment, I reshape what is invisible in you, as you respond to what I experience while you explore the invisible in me; and as we pass from moment to moment you reshape my responses (which are hardly verbal and mostly corporeal). Each of us contributes his/her novelty to that which emerges between us. Our exchanges, verbal and corporeal, have become an original dialogue, distinguished from the set phrases of ordinary speech and scholarship alike by the uniqueness of what has come into being entre nous. We have to work at finding a way to articulate the emerging of this intimate mystery between us, a language that does not betray with nouns the greater process to which our intimate selves belong, a way of speaking that does not constitute an obstacle to giving oneself over to the mystery that is so far beyond us (even though we both take part in it). This new language serves as a sign that this mystery founds a poetic way of dwelling that we are coming to inhabit.

My new flesh is a gift of your attention. As you explore me, you reconnect me to myself. As you explore me, you allow me to collect myself. I know myself as, at once and with no distinction, a body (a thing) and a subject—the subject/object dichotomy on which epistemology founders is here overcome, for I know myself both as an object with a subjectivity and as an embodied (material) subject. More than that, I know that it is my flesh that knows your embodied (material) subject as flesh. I know you both as a subject that left her impress on the fibers of my flesh and as a subject that transcends me. A truth shines in what is between us—an unveiling that lets me come forth as one-to-be-seen by you. In the same act of unveiling, this truth reveals you as the one who bids me to reveal myself. Your look and the way you explore all of me almost completely restores to me an archaic and innocent flesh—you can re-endow me with all that I lost, and you can do this even though, in this situation, you are not as archaically innocent as I. Ever so softly, I am marked by the invisible imprint of your flesh—your eyes, your attention, the shape and dynamic of your gestures—whose strength is taken into this new flesh that emerges in the space between us. Your attention transfigures me. As you explore me with a frankness that lets me know I must will to conceal nothing from you, in order to be able to accept from you that gift of becoming wholly transparent to your regard.

Yet somehow, though it is born in the space between us, the flesh you grant me comes forth as my very ownmost being. This reality which is between us now founds what has become most privately mine. Attuning myself wholly to your exploring me according to my hopes, you have effected an alchemical transformation of my energies, which you, by your openness to my innocence, take within you, transform again, and project back to the between that has emerged entre nous. In focusing so intently (as you imagine/observe what part of me you will photograph, and how you will photograph it) on the energy you project into the space between us, you allow me to remake myself again and to put on ever more primeval bodies of innocence. This entre nous focuses my desire and my attention (as I hope it focuses yours): it focuses my attention because, nude before you (and in relation to you), I feel so much more intensely, and the intensity of the feeling makes me gratefully aware that only flesh has the privilege of responding to flesh. Yes, it is also true that only flesh can respond feelingly to things, but that seems of no importance right now: what occupies my attention is how my flesh responds to your eyes, to your attention, to your gestures and to what your eyes and gestures tell me about how your flesh responds to mine. I attune myself to those energies with an attention complete enough to become prayer.

I am transformed in such a way that my will and seeing have become fused; my seeing has become a form of longing. It is full of intent. The intentness with which you look at me has excited an energy in me that connects to something archaic, something beyond myself. My thinking/desire belongs to an elsewhere. There I become a globe of seeing that allows me to experience you seeing me, even as your looking responds magically to the energies you create in me. I know you as opening me to a self-knowledge that is your gift. I know you as knowing me as I would be. I know you as experiencing and accepting my fundamental innocence, for you look on me wholly and with innocence.

Despite my awareness you can perceive what is invisible in me, as I perceive what is invisible in you, the asymmetry in our relationship, that I give myself to be seen by you in a way different from the way you give yourself to be seen by me, makes a discomforting truth appallingly evident: that there is no fusion, no merger here. The relationship we have right now is so intensely intimate and personal that I long for it to complete (to perfect) itself by becoming a total identification, which would allow me to experience your flesh experiencing my flesh. Still, I know that can never be, for your consciousness, in all its specificity, transcends what my flesh can know. You cannot be reduced to me, nor I to you. By reason of your freedom, you transcend me (as I transcend you). Even though, here, I expose myself naked to you, lying back here in pose that amounts to a plea for you to explore me totally and intimately, I seek to initiate a process that will expand until it engulfs us completely and obliterates all that is not uniquely between us—even though my nudity pleads for you to give yourself over to me, to abandon your autonomy and to suffuse yourself through me, to entirely become nothing but me—I have to acknowledge your freedom and your transcendence. The tension here between the fantasy and reality, between desire and truth, intensifies my arousal.

Even as I solicit your attention, I sense you escaping from me. But I also know that you, whose role in this play is consolidated in your eyes and hand, cannot be exchanged for me, whose role is to show himself as completely and intimately as possible. But the impossibility of substituting “the one” for “the other” is not the result of one of us being active, the other passive—of my being the passive recipient of your attention. I desire to show myself in a way that will allow me to be perceived; and you, for your part, to perceive the invisible in me, have had to open yourself to these intimate communications that I would not offer to just anyone. You have had to allow some part of you to become still and receptive, to accept what I want to tell you with my nudity. My uniqueness, your uniqueness, the uniqueness of what emerges between us, is absolutely crucial here. If I caress myself, if I electrify myself, I do it with energies that arise between us, entre nous, and I do this because I want to show myself this way and, more importantly, I want you, in your uniqueness, to see me this way. What is more, it shows that I want something unique, that I would not share with just any other, to emerge between us. I rely on your accepting my plea to be seen this way. I rely on your openness to having your actions shaped by what you perceive in me when, through the positions I adopt and my actions, I implore you to receive my desires. I rely on your agreeing to become open and receptive so that what I want to impart to you will impress itself on you (or on what your being contributes to the reality that emerges between us) in a similar way as your attention penetrates me and leaves its imprint in the energies that bring forth this new flesh I experience as delight. I rely on your acknowledging, as I open myself to you, as I offer myself as a to-be-seen, that this energy will expand and overwhelm all else that is between us. My offering my materialized body-of-energy as a to-be-seen implores that you will allow that energy to be become a globe of electricity that will see us both, and see in both of us our seeing one another. Like Fa Zang’s mirrors.

Because you transcend me and I transcend you, there is a mystery between us. Though what has come forth between us enables me to perceive the invisible in you, I do not see all of you, just as you cannot, despite my nudity, see all of me. Each of us shelters a mystery that inhabits what has emerged entre nous deux, something that is as archaic as the species and yet is renewed with every intimate encounter. The perceptible invisible in you is animated by this mystery, as are the secret desires that I harbour and I earnestly hope you can perceive.

This mystery is common to us both and protects what has re-emerged in what is entre nous deux. This mystery is the basis of another, more profound reality between us: as I perceive the invisible in you and you perceive the invisible in me, we, both of us at once, sense a common invisibility. I perceive what is invisible in you perceiving what is invisible in me and my efforts to have you sense the invisible in me rely on my capacity to sense what is invisible in you and, as though magically, to affect what pertains to your ownmost being. The body you see when you look at my nude form and the body I see when I look into your eyes become a bridge to the invisible that, though deeply within each of us, is also common to us both. We have this mystery in common because, though in our flesh, it overlaps a larger, more archaic mystery. So important is the commonality of our joint experience of the invisible that, if I experience your attention lapsing, I cannot bear to give myself to you to be seen. Reciprocally, whatsoever you endow my perception with cannot impress itself onto my being except insofar as I accept it as belonging to the reality of what is entre nous. When you avert your attention from me, that reality that has emerged between us becomes enfeebled—the bridge of energies between us disappears and you cease remaking me. Thus, I cherish your attention, as a form of praise between what is ancient in your gender and what is ancient in mine.

I sense the nakedness of my face as a most profound nudity, for its openness reveals how deeply you stir me. The more you stir me, the nearer I am brought by those energies you grant, the more naked my face seems to me. The eroticized flesh with which you have endowed me allows me to see your face in a glory that illumines it. I hope that you see my face in somewhat the same way. My nudity and openness seek you and you respond with an extraordinary attunement that is already clear in the mirror choreography of my showing and your exploring, but is revealed with an even more raw intensity when you stop shooting and your eyes peer into mine and you survey my inner state. You see into me when you turn your attention to my face, or when you stop shooting and your eyes meet mine. I long to mirror your seeing into me—to have myself see into you as you see into me and to have my seeing into you energize you as your seeing into me electrifies me. Even more, I long for you to know me exactly as I know you and for me to know you exactly as you know yourself: for you and I to know each other fully, with no part reserved from the other, for us both to be completely transparent to the other. At the same time, I know that is simply an archaic fantasy: while you see into me and seem wholly attuned to me, at the same time, your transcendence, your freedom, prevents this longing from being fulfilled. Despite the solicitations my nakedness offers, you remain beyond me.

Thus, though I refind myself through you, you remain an inappropriable transcendence. I perceive you, as you explore me, as being at once both immanent and transcendent—both entirely here, specific, concrete, a self-identical and determined being and yet free, mutable, indeterminant, open, protean—one who exceeds any conceptual effort to fix her. What is more, the relationship we have forged is nonreciprocal. I present my nakedness to you, to be explored (my nudity is a plea for you to explore me)—but to this vulnerability which I am, you seem infinitely remote—remote to the point that one aspect of the relationship is startlingly impersonal. You reach into my innermost being—but you remain in the Beyond and seem to me, in my vulnerability, to be infinitely remote, infinitely other, an infinite noema beyond all my noeses. And while, for me, you are infinitely remote, I, for myself, am entirely here, in this extremely elastic now (time, too, has changed for me), pleading for your eyes, my nudity a sign of my consent to be penetrated by your attention.

Because I cannot reach you, because you explore me without submitting to being explored yourself, I do not consume and exhaust you. You make me from on high. Yet at the same time, you undo me, and make me selfless: my attention to the energy you impart to me becomes so complete and total there is no room left over for an “I.” Your transcendence, your resistance to my wishes, reveals itself as an obstacle to fantasies and wishes; it reveals the reality of your otherness. This otherness appears to have two aspects. The first stems from your freedom: because we are not fused, because we are not truly at one, I cannot compel you to turn your attention here or there. The second arises from your ontological status a material being belonging to nature. In general, matter seems to be inert to our desire, and, more specifically, I know your body and its biochemical constitution can put up a nonresponsive resistance and inertness to my wishes and my desires. In having to acknowledge the material basis of your flesh, I am obliged to recognize the strict limits you put on my desire’s capacity to respond until it consumes you and your world (until it is merely an aspect of mine). Acknowledging those limits has a role in ordering this new world—but it also represents an intrusion of the world of ordinary matter into the different reality that is between us (a reality of energy, vibration, intensity, electricity, arousal).

Desire’s drive is to expand the reality of energy, electricity, and arousal until it consumes entirely the realm of ordinary matter; but matter thwarts desire. So, following the edicts of desire, I feel myself becoming less material (as vibratory pulsions and electricity come to constitute the world of which I am aware and to which my flesh belongs); and as I become less material, I feel myself becoming increasingly transparent to your attention. As you explore me, your attention produces a flux, a pulsion, in me that demolishes completely my reserve, my inhibition, my need to keep myself to (and for) myself. The energy you give me suffuses me, stirs in all parts of my flesh, from my head to my toes. It strives to expand, and as it does so, it sunders me, and brings forth a new self as a double form: first, the passive being who receives himself through you and so exposes himself to you as one who longs to be loved (who longs to be, at least for the duration of this elastic present, the only object of your fascinated attention); and, second, the active being who wants to show himself and in doing so induce energy in you. This new self is a double, too, in that I become at once, fully animated with an unusual intensity and yet wholly passive: active because I strive with every fiber of my being to impel you to explore my ownmost parts; and passive because I want to give myself wholly over to being bathed, in every inch of my physical being, in the warm globe of your attention, which radiates throughout my entire body and calms all striving. As for the active aspect of my being, it seems to arise from the blood and the pulse that drives the blood. The Ayurvedic tradition describes flesh as being made from blood and belonging to blood, and I can feel the truth of the claim in my very physical being. As for the passive aspect of my being, it is so completely suffused and reanimated by the complete and perfected reality that your attention opens me toward: being enveloped and enfolded in your attention opens me towards a more loving reality, in which I am bathed in the glow of a subjectivity that is no longer entirely yours, or entirely mine. It opens me to the truth of the completion. That complete and perfected reality we have in common stills me utterly, even while it stimulates me extraordinarily. I collapse into a feeling of wholeness and the intensity that permeates all of me makes me aware in every part of me that all my being is flesh that longs to show itself and to be seen. I sense myself as flesh, pure flesh, a puppet of a species memory that you awaken in me.

Though it is so deeply me, the new flesh I receive from you is beyond being controlled by my intention because it is stronger than my intention. (2)

Flesh, though spiritual, seems to clear away the fiction of the isolated ego and to join with the flesh of the world, in all its spiritualized materiality. I receive this new flesh from you with the utmost of passivity. Your attention falls on me and floods me. Once I resolved to give myself to you, all I wanted was to become the exclusive object of your attention. It is passivity I seek. In giving myself to you to be explored intimately by your eyes, I resolved to become passive, to allow myself to be swamped in the flood of your attention and in the entre nous that would emerge, thanks to your concentrated, focused attention. I long to become still, to do nothing, and to let myself become nothing but the innocent object of devoted attention. Yet that theme of the double again obtrudes on my feelings, for, while relishing by passivity, I have never felt more alive, never felt more vital, never felt more dynamic, never felt more aware of myself than when I feel the surge of energy that occurs when I notice your eyes and your gestures show that you are seized by the task of exploring me completely. So, even while your attention sweeps over me like a flood and renders me passive to a degree that only infants can normally know, I also feel enlivened. I tingle as I feel my energies pouring out of myself and enveloping you, in an effort to command your attention. My urge to become ever more completely the object of your attention is not something abstract. Rarely do I sense so intensely that my aims and my wishes are bodily—every least detail of the relationship that is emerging between us is bodily. I experience this recorporealization of my thinking and my being as delight, for with it comes an exhilarating sense of freedom that is your greatest gift to me, a gift that provides the energy that eroticizes my flesh and raises my feelings of being sexuate to such vitality that it comes to constitute the horizon of awareness

Electrology: Thought Remade by the Rise of the Science of Electomagnetism

Marshall McLuhan suggests that electrotechnics (the human use of electromagnetic phenomena to intervene in nature) inaugurates a new era in cultural history. He is right about that, of course. However, identifying when this change occurs has its challenges: two books by the Italian curator, art historian, and literary critic Renato Barilli, L’alba del contemporaneo: L’arte europea da Füssli a Delacroix (The Dawn of the Contemporary: European Art from Füssli to Delacroix, 1996) and Scienza della cultura e fenomenologia degli stili (The Science of Culture and the Phenomenology of Styles, 1991, new edition, 2006; English translation, 2012), offer insightful commentaries on the issues of dating the beginning of the new age (which, in keeping conventions in philosophy) we do well to call the postmodern age (the modern era beginning with the Renaissance and marked by a quest for a verisimilar, naturalistic art). Two momentous discoveries that occurred just a few years apart introduced the material changes with which one might mark the beginning of the postmodern age: the first was Luigi Galvani’s (1737–98) publication of De viribus electricitatis (1791), reporting his discovery of a form of electric current passing along a frog’s nerve tissue and causing its leg muscles to contract; the second was Alessandro Volta’s (1745–1827) invention of the voltaic pile (1799).

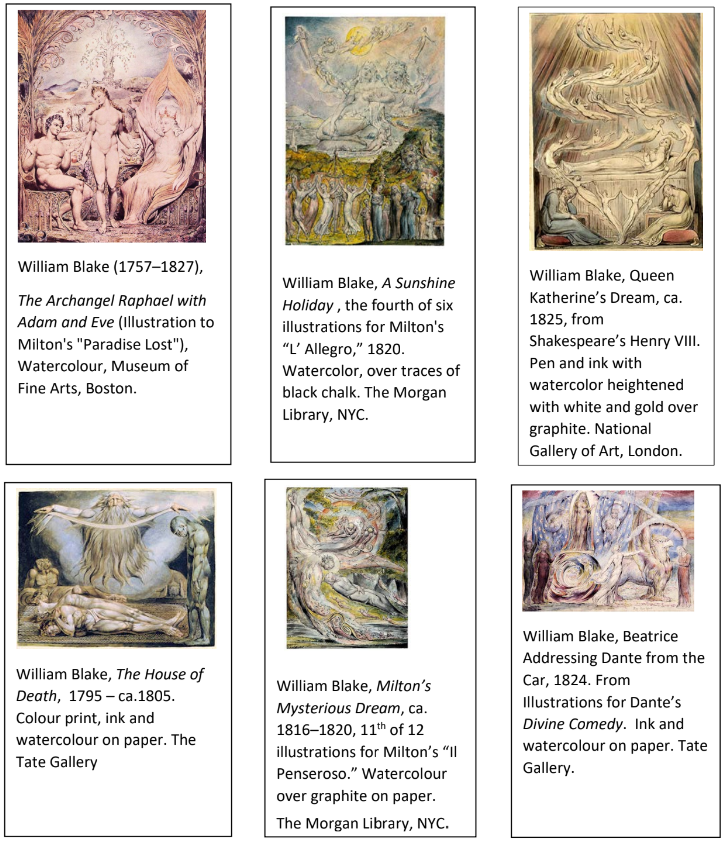

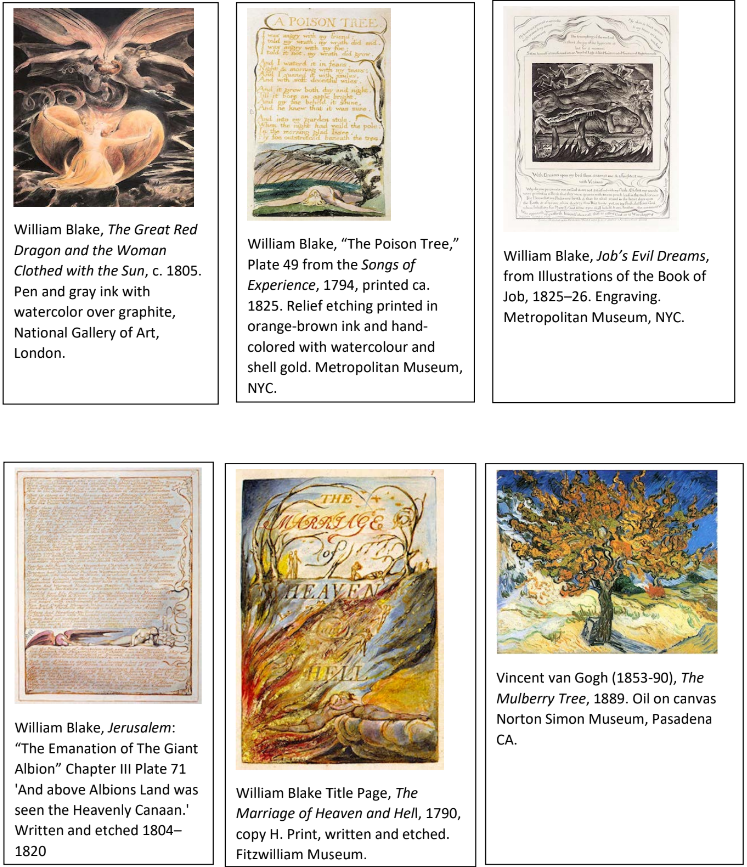

However, it is only in the later part of the nineteenth century (around 1860, Barilli suggests) that this new era began to manifest itself as an intellectual and symbolic force. Given the separation of six decades (and perhaps more), is it possible to maintain that the material and the symbolic strata of culture are connected? It is important to maintain that connection if we want to argue that electrotechnics are connected to the characteristics of the art of the era. Barilli responds brilliantly to this problem. His first tack is to deny that so many decades separate the first changes that occur in the material stratum of culture from the first changes that manifest themselves in culture’s symbolic stratum. He does this through a staggering insight: the first artists whose works reveal an imagination (and technique) shaped by electromagnetism are William Blake (1757–1827) and the Swiss-English painter Henry Fuseli (German: Johann Heinrich Füssli, 1741–1825). Blake he astutely describes as a “prophet of the wave of energy in human beings about to appear in all expressive graphic and literary forms.”(3) The Marriage of Heaven and Hell (1793), among the densest and richest of Blake’s wondrous prophetic books, avers that “Energy is the only life and is from the Body and Reason [for Blake a confining agency] is the bound or outward circumference of Energy. Energy is Eternal Delight.” Blake writes this, Barilli notes, at just the moment when nascent discoveries in electromagnetism appear with greater frequency. The development of the new conceptual regimen—a paradigm I refer to as the electrological paradigm—brought with it a new philosophical anthropology: the deep, uncontrollable passions depicted in Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s (1749–1832) Die Leiden des jungen Werthers (The Sorrows of Young Werther, 1774, revised edition 1787) or the irresistible attractions between lovers in his Die Wahlverwandtschaften (Elective Affinities, 1809), Barilli notes, are understood as an irresistible attraction, as a kind of electromagnetic force of attraction that cannot be resisted.

From this point on (when Blake and Goethe begin to explore the new sentimental map), “we” are split in two: a superficial will controlled by Urizen, where we try to respect all the formal obligations, the norms of respect and social convention, and a “deep,” unlimited, and uncontrollable will that constitutes a unique reality with the very wellsprings of Life and Energy. However, “we” are always ourselves. The personality is split into two halves that have different origins: one conforms to the outmoded criteria of the rationalist age (mechanical, Gutenbergian, “modern”), while the other adopts to the “newest” demands of the electric world. (4)

The visual art of the modern period, from the Renaissance to the final decade of the eighteenth century, was dominated by the idea of drawing bodies by projecting rays from the object onto a two-dimensional plane. The Gutenbergian/Newtonian episteme had made the idea of perspectival distance integral to the concept of seeing: the modern conception understands seeing as an act that takes place at a distance, across an empty medium, or, at least, one that does not present obstacles (if space is understood as filled with “atmosphere,” then the particles that make up these atmospheric gasses are understood as particles that reflect rays—that is made evident by aerial perspective).

The mirror and the camera obscura are natural guarantees of the validity of a similar type of “reflection,” of representing reality to which both the theories of artists from Alberti’s time onward and “machines,” the technological inventions coming to photography and its derivatives, make reference. (5)

The new discursive regime—which began with Galvani and Volta and consolidated itself in the theories of Michael Faraday and John Clerk Maxwell, distilled into the mathematical form through which they have become known, in Maxwell’s 1865 paper, “A Dynamical Theory of the Electromagnetic Field”—mandates different forms of representation. Renato Barilli set them out, lucidly:

Now, the concept of the mirror wanes. Humans “know” by sending into the atmosphere beams of concentric waves that quickly envelop objects, constantly changing the point of view and superseding that logic by substituting it with another in which “the centre is everywhere” and three-dimensional objects physically present, ready to be manipulated. . . . On the other hand, a similarly ubiquitous presence of three-dimensional objects, owing to the possibility of enveloping them with wave trains, acquires a dematerialized quality. (6)

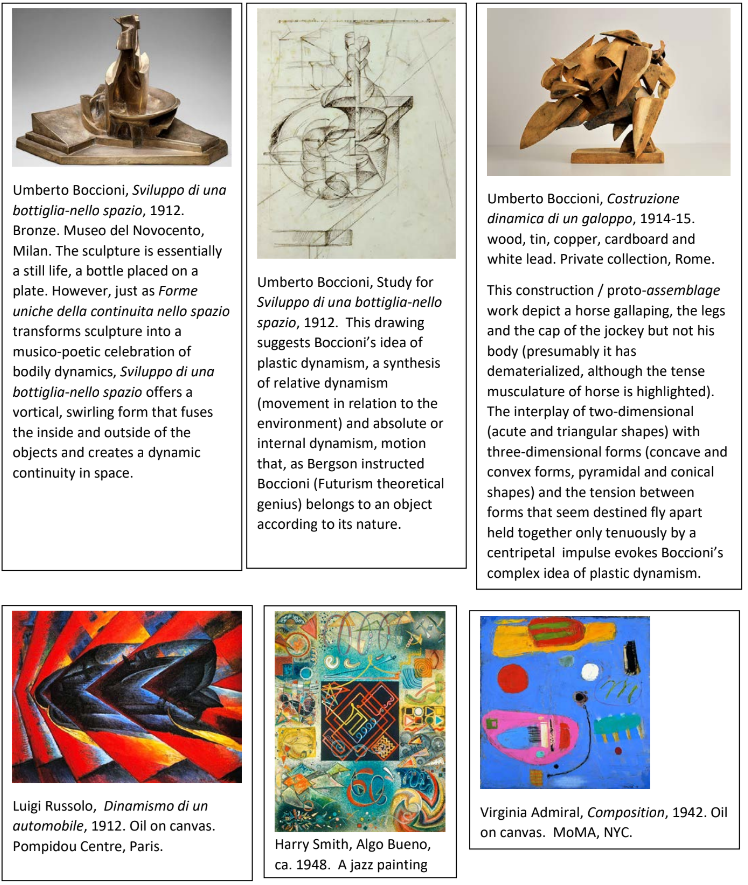

The topoi and tropes of the new discursive regime Barilli describes are evident in a remarkable text “Fondamento plastico della scultura e pittura futuriste” (The Plastic Foundations of Futurist Sculpture and Painting), by Umberto Boccioni. At one point, Boccioni lays out his idea of atmosfera (atmosphere):

When I say that sculpture must try and model the atmosphere, I mean that I want to suppress, i.e., FORGET, all the traditional and sentimental values concerning atmosphere, the recent naturalism which veils objects, making them diaphanous or distant like a dream, etc., etc. For me atmosphere is a materiality that exists between objects, distorting plastic values. [This can be taken as expressing the idea of infinite plasticity and its connection to electrology.] Instead of making it float overhead like a puff of air (because culture taught me that atmosphere is intangible or made of gas, etc.), I feel it, seek it, seize hold of it and emphasize it by using all the various effects which light, shadows, and streams of energy have on it. Hence, I create the atmosphere!

When we begin to grasp this truth in Futurist sculpture, we shall see the shape of the atmosphere where before there was only emptiness or, as with the Impressionists, mist. This mist was already a step toward an atmospheric plasticity, toward a physical transcendentalism which, in turn, is another step toward the perception of analogous phenomena that have hitherto remained hidden from our obtuse sensibilities. These phenomena include perceiving the luminous emanations of our bodies, of the kind I spoke of in my first lecture in Rome, and which are reproduced in photographic plates. (7)

Interests in spirit photography, light emanating from bodies, and atmospheric plasticity leading towards physical transcendentalism are certainly a long way from the notion of Futurism that dominates art-historical writing—that it is “machine art,” with the term machine understood as later twentieth- and twenty-first-century thinkers conceive it. Boccioni goes on to relate the idea of atmosphere to the Faradayan conception fields of electromagnetic energy and that Faradayan field conception to the idea of vibratory reality, that benchmark esoteric notion.

Now this tangible measuring of what formerly appeared to be empty space, this clear superimposition of new strata on what we call real objects and the shapes that determine them—this new aspect of reality is one of the foundations of our painting and sculpture. It should now be clear, then, why endless lines and currents emanate from our objects, making them live in the environment which has been created by their vibrations.

The distances between one object and another are not just empty spaces, but are occupied by material continuities made up of varying intensities, continuities we reveal with perceptible lines that do not correspond to any photographic truth. That is why our paintings do not have just objects and empty spaces, but only a greater or lesser intensity and solidity of space. (8)

This remarkable passage, written by Futurism’s true theoretical genius, demands commentary. It states the universe is a plenum, “filled” with a material substance “that exists between objects” and is affected by “streams of energy.” This atmosphere, Boccioni suggests, is nothing like that of the Symbolists, a veil that makes objects appear “diaphanous or distant like a dream.” (9)

Boccioni’s connection of what he conceives as atmosphere with luminous emanations from bodies gives additional reason to believe that the phenomenon he is describing is an electromagnetic field propagating itself through space in the form of Hertzian waves. It explains his maintaining that it should “be clear . . . why endless lines and currents emanate from our objects, making them live in the environment [the electromagnetic field] which has been created by their vibrations.” Boccioni also draws on one of the topoi of electromagnetic esoterism (one that can be traced back to Neo-Platonist metaphysics or emanationist metaphysics of whatever stripes), namely that the different levels of reality are formed of energy that has congealed in different measures. Thus, space—a plenum—is filled with materials (electromagnetic energy) of different intensities. Boccioni even relates (in a manner consistent with electromagnetic theory) the linee di forza of Futurist painting to these varying intensities. The artist-theorist draws on Henri Bergson (1859–1941) to support this electromagnetic metaphysics: Boccioni construes Bergson as saying that reality is fundamentally constituted of varying intensities of energies and motion. He even implicitly makes a connection that other early twentieth-century artists also made, between the phenomena of thought-forms and electromagnetic waves transmitted through the æther. Concerning the new sensibility that results from rigorous spiritual and religious preparation (a theme of Annie Besant and C. W. Leadbeater’s Thought-Forms, 1901), Bocciani states,

Between the physical body and the invisible there is a space of vibrations that determine the nature of its action and dictates the artistic sensation. In short, if spirits wander around us and if they are observed and studied; if fluids of power, antipathy, and love emanated from bodies; if deaths are foreseen from a distance of hundreds of kilometres, if premonitions fill us with joy or annihilate us with sadness; if this entire impalpable, invisible, inaudible realm is becoming increasingly the object of investigation and observation—all this happens because in us a marvellous sense is awakening thanks to the light of our consciousness. Sensation is the universal garment of the spirit and it is now appearing to our clairvoyant eyes. And with this the artist senses himself in everything. By creating he does not look, observe or measure—he senses and the sensations that envelop him dictate to him the lines and colours that aroused the emotions that caused him to act. (10)

The ideas and motifs in this passage are remarkably close to those of Thought-Forms, but the fact that it followed remarks on electromagnetic phenomena suggests Boccioni, like so many other artists from the early twentieth century (and the genius Harry Smith), believed thought-forms to be electromagnetic events.

Boccioni’s affirmation that “it should be clear . . . why an infinity of lines and currents emanate from our objects, making them live in the environment created by their vibrations” merits further attention. For this remarkable passage (and its context) has not been understood for what it really is, namely an affirmation of Faraday and Maxwell’s ideas on electromagnetism. At the moment Boccioni wrote this pioneering text of electrological aesthetics, ideas about electromagnetism were collecting themselves into a force that would transform the material and symbolic cultures of the West. This transformation would be the most momentous in the West since Johannes Gutenberg’s (1400–1486) invention of moveable type (1439); further, its geo-cultural reach would extend farther, for this transformation would change the entire world as fundamentally as Gutenberg changed the West.

Marshall McLuhan understood the character of this transformation. One of the longest quotations in all his writings was drawn from Albert Einstein’s (1879–1955) forward to Max Jammer’s (1915–2010) Concepts of Space: The History of Theories of Space in Physics (1954), concerning the bypassing of absolute forms by means of a dynamic, non-homogeneous field:

The victory over the concept of absolute space or over that of the inertial system became possible only because the concept of the material object was gradually replaced as the fundamental concept of physics by that of the field. Under the influence of the ideas of Faraday and Maxwell the notion developed that the whole of physical reality could perhaps be represented as a field whose components depend on four space-time parameters. If the laws of this field are in general covariant, that is, are not dependent on a particular choice of coordinate system, then the introduction of an independent (absolute) space is no longer necessary. That which constitutes the spatial character of reality is then simply the four-dimensionality of the field. There is then no “empty” space, that is, there is no space without a field. (11)

McLuhan goes on to point out that Timothy H. Boyer’s Scientific American article makes the same point, that the classical vacuum “is not empty. Even when all matter and heat radiation have been removed from a region of space, the vacuum of classical physics remains filled with a distinctive pattern of electromagnetic fields.” (12) McLuhan also quotes Francis M. Cornford’s “The Invention of Space”: “geometrical space was seen to be continuous, not a pattern of empty gaps interrupted by solid things; it penetrates the solids that occupy its single continuous medium.” (13)

A hotly contested debate concerning the nature of electricity and magnetism took place in the 1860s, 70s, and 80s between followers of Isaac Newton (1642–1727) and those who sided with Michael Faraday. Though it is not yet a standard part of every school child’s learning, it should be: knowledge of it is essential to understanding the postmodern condition. The Newtonians modelled their understanding of electricity and magnetism on the scientific theory of gravity. The Faradayans, by way of contrast, modelled their understanding on the theory of heat flow, worked out by William Thomson (later Lord Kelvin, 1824–1907). Very soon after he promulgated them, Newton’s laws of motion and gravity were widely embraced and became the standard model for dynamics. They achieved this status despite having a troubling feature. Physical forces generally operate through contact: I need a clear space on my desktop to put down my bowl of soup, so I place my arm against some of the books cluttering it and shove them out of the way. My arm is in contact with the books and the kinetic energy it exerts on the books moves them out of the way. But Newton wanted to demonstrate that a gravitational pull, exerted by the sun, keeps the earth moving in its elliptical orbit. Against the intellectual climate of his times, Newton conjectured that space is a void—empty, a vacuum. This meant that gravity was to be understood as a new kind of force that does not operate through contact: space is a vacuum, and yet the sun can exert a gravitational attraction on the earth. The sun’s gravity acts on the earth at a distance.

Magnetism seemed similar to gravity in respect to being a force that acts at a distance: when a nail is placed near a magnet, but not in contact with it, it is attracted to the magnet. Both gravity and magnetism involve separate bodies that exert an attraction on one other: both seemingly act instantaneously and without any necessary physical contact between the two. The force of attraction/repulsion between two electrically charged bodies acts similarly. Newton’s prestige and the success of his theory of gravity lent support to action-at-a-distance accounts of electromagnetic attractions and repulsions. Newton’s formula for calculating the gravitational attraction between two bodies is F = m1m2Gr2, where m1 is the mass of one of the bodies, m2 the mass of the second, r the distance between the bodes, and G is a constant of proportionality (known as the gravitational constant). (14) In 1785, the French physicist Charles-Augustin de Coulomb (1736–1806) worked out a formula for calculating the attraction or repulsion between two bodies charged with static electricity. It turned out to be F = q1q2Ker2, where q1 and q2 are the respective charges on the two bodies, r is the distance between the two charged bodies, and Ke is a constant of proportionality (known as Coulomb’s constant, the electric force constant, or the electrostatic constant). That both formulae have the same pattern lent further weight to the supposition that electric and magnetic forces of attraction and repulsion are, like gravity, action-at-a-distance forces. The supposition seemed virtually established—only the details (and the development of a formula similar to Coulomb’s for electric currents) needed to be worked out.

Faraday wasn’t willing to go along with the supposition. He was staunchly independent-minded. He hailed from the working class and had little formal education: he started as an apprentice bookbinder and his interest in learning developed as a result of taking home and reading some of the books he was gluing and sewing together. One of these was Isaac Watts’s (1674–1748) The Improvement of the Mind (1741), a work that offers counsel on developing one’s intellectual abilities (he recommended, for example, keeping a notebook and corresponding with friends to get practice in expressing one’s ideas). Faraday applied its recommendations assiduously. He came to have that quality so common to autodidacts: he habitually considered topics from first principles, and he wanted to find out each fact for himself. Those intellectual dispositions made him one of the greatest experimentalists of all time. And, like many autodidacts, he suffered from too much diffidence—near the beginning of his career, he hired an elocutionist to attend his presentations so he (the elocutionist) could help Faraday overcome his working-class diction.

In 1831, Faraday discovered electromagnetic induction and formulated a law concerning the phenomenon: his law is one of the most basic laws of electromagnetism—it predicts how a magnetic field will interact with an electric circuit to produce an electromotive force (the force we now know propels electrons into motion). The law has wide-ranging application and helps explain the operation of transformers, inductors, electric motors, and electrical generators. Following on on this discovery, Faraday attempted to form a picture of how a magnet interacts with a wire to induce electricity. His sturdy independence of mind, along with his meagre mathematical skills, resulted in his conceiving a picture of the induction process that is fundamentally different from the one that would have been produced by applying the Newtonians’ supposition about the nature of electricity and magnetism. Newton was befuddled when he asked how gravity is transmitted through space. But he recognized the assumption that it leapt from the sun to the earth actually worked (that is, predictions based on that assumption were confirmed through observation). So he reluctantly accepted that supposition. Faraday, on the other hand, insisted on asking how electromagnetic forces are transmitted (and that led to his important role in creating the postmodern epistēmē). Faraday was convinced that something must exist between the wire and the magnet. He called that something a “field” and pictured it as an area filled with strings (like the string that can be used to pull an object) or lines of force. Faraday in fact went so far as to claim that force is a substance—indeed the only substance.

All the different manifestations of force (namely, gravity, electricity, magnetism) are interconvertible, as all are simply activities of the basic, underlying substance. This hypothesis was not taken up by subsequent scientists, including Maxwell, who played a cardinal role in laying the foundations of the science of electromagnetism; nonetheless, it appealed to many, if not most, artists who embraced the cosmopoetic ideas of the new science.

In a lecture on 21 April 1820, the Danish chemist and physicist Hans Christian Ørsted (sometimes Oersted, 1777–1851) took note that a compass deflected from true north when an electric current from a battery was switched on or off. When he investigated the phenomenon, he determined that an electric current passing through a wire creates a circular magnetic field around the wire. André-Marie Ampère (1775–1836) took Ørsted’s experiments a step further, by demonstrating that parallel wires carrying electric currents attract or repel each other—they repel each other if the currents flow in the same direction, and attract one another if the currents flow in opposite directions. He developed generalized laws, expressed in mathematical form, showing that currents have measurable and predictable magnetic effects. The best known (now called Ampère’s law) states that the electromagnetic interaction of two lengths of current-carrying wire is proportional to their lengths and to the intensities of their currents.

Ampère was a Newtonian, and his mathematical description of the magnetic effects produced by electricity depended on action-at-a-distance theories; moreover, the explanation was modern in the sense that it simply predicted regularities in the succession of observations. James Clerk Maxwell began considering Faraday’s field ideas, and felt a disconnect between the physical phenomenon Ørsted observed and Ampère’s mathematical description. Maxwell’s friend, William Thomson, had suggested an analogy among electricity, magnetism, and heat flow. I must oversimplify in commenting on this, to keep the account to a reasonable length: using a mathematical operator known as a gradient (informally, the gradient extends the operation of taking a derivative to apply to functions of multiple variables) allowed Fourier to compute the direction of a heat flow. In the end, he was able to show the existences of lines (directions) of heat flow. Thomson imaginatively connected Fourier’s lines of heat flow to the flow of electricity and the radiation of magnetic energy. Maxwell took a cue from that and set out to develop a mathematical formalism for Faraday’s ideas.

Maxwell’s decision was a bold and courageous move, especially for a young physicist who still needed to solidify his reputation. The physics establishment was almost entirely on the side of the Newtonians; Faraday’s ideas about fields and lines of force seemed to them like vague and amateurish conceptions developed by somebody who lacked the requisite mathematical skills to do real physics. On 10 December 1855 and 11 February 1856, Maxwell read his first paper on electricity to the Cambridge Philosophical Society (it was subsequently published in the society’s Transactions, vol. 10, part 1): its title was “On Faraday’s Lines of Force.” There he explains lines of force in the following way:

When a body is electrified in any manner, a small body charged with positive electricity, and placed in any given position, will experience a force urging it in a certain direction. If the small body be now negatively electrified, it will be urged by an equal force in a direction exactly opposite.

The same relations hold between a magnetic body and the north or south poles of a small magnet. If the north pole is urged in one direction, the south pole is urged in the opposite direction.

In this way we might find a line passing through any point of space, such that it represents the direction of the force acting on a positively electrified particle, or on an elementary north pole, and the reverse direction of the force on a negatively electrified particle or an elementary south pole. Since at every point of space such a direction may be found, if we commence at any point and draw a line so that, as we go along it, its direction at any point shall always coincide with that of the resultant force at that point, this curve will indicate the direction of that force for every point through which it passes, and might be called on that account a line of force. We might in the same way draw other lines of force, till we had filled all space with curves indicating by their direction that of the force at any assigned point.

We should thus obtain a geometrical model of the physical phenomena, which would tell us the direction of the force, but we should still require some method of indicating the intensity of the force at any point. If we consider these curves not as mere lines, but as fine tubes of variable section carrying an incompressible fluid, then, since the velocity of the fluid is inversely as the section of the tube, we may make the velocity vary according to any given law, by regulating the section of the tube, and in this way we might represent the intensity of the force as well as its direction by the motion of the fluid in these tubes.

The configuration of lines of force are captured in the patterns that iron filings make when spread evenly over a sheet of paper and the pole of a magnet held against the paper—“Hast ‘ou seen the rose in the steel dust / (or swansdown ever?),” asks Pound, that great pioneer (along with James Joyce) of electromorphic literature—and he continues “so light is the urging, so ordered the dark petals of iron / we who have passed over Lethe. (15) ” In “Vorticism” (an earlier work, from 1915), he writes somewhat less poetically,

An organization of forms expresses a confluence of forces. These forces may be the “love of God,” the “life-force,” emotions, passions, what you will. For example: if you clap a strong magnet beneath a plateful of iron filings, the energies of the magnet will proceed to organise form. It is only by applying a particular and suitable force that you can bring order and vitality and thence beauty into a plate of iron filings, which are otherwise as “ugly” as anything under heaven. The design in the magnetised iron filings expresses a confluence of energy. It is not “meaningless” or “inexpressive.” (16)

In this case, regarding its role in his great long poem (perhaps the greatest written in the English language in the twentieth century), it is clear that the influence of the magnet on the iron filings is an image of the Mystery ordering the material world so as to manifest beauty. Pound’s essay “Cavalcanti” observes that we “appear to have lost the radiant world, where one thought cuts through another with clean edge” (i.e., a world of compenetrazione); he continues with a vision of the paradisiacal realm, “a world of moving energies ‘mezzo oscuro rade,’ ‘risplende in sè perpetuale effecto,’ magnetisms that take form, that are seen, or that border the visible, the matter of Dante’s paradiso, the glass under water, the form that seems a form seen in a mirror, these realities perceptible to the sense, interacting, ‘a lui si tiri.’” (17) He contrasts this with the world of “modern” (along with Barilli, I would have used the term “postmodern”) science:

For the modern scientist energy has no borders, it is a shapeless ‘mass’ of force; even his capacity to differentiate it to a degree never dreamed by the ancients has not led him to think of its shape or even its loci. The rose that his magnet makes in the iron filings, [sic] does not lead him to think of the force in botanic terms, or to wish to visualize that force as floral and extant (ex stare). [Pound is absolutely right that the electromorphic realm is phytomorphic—and he is likely right that scientists, to which I would add some new media artists, fail to see this.]

A medieval ‘natural philosopher’ would find this modern world full of enchantments, not only the light in the electric bulb, but the thought of the current hidden in air and in wire would give him a mind full of forms, ‘Fuor di color’ or having their hyper-colours. The medieval philosopher would probably have been unable to think the electric world, and not think of it as a world of forms. Perhaps algebra has queered our geometry. (18)

Newtonians would have considered the patterns the iron filings form as showing the cumulative effects of the magnet acting individually on each particular particle—one would take each iron particle, one by one, and calculate the effect on it of the north pole and south pole of the magnet, taking into account the distance of the particle from each of pole. They saw no need to take into account the complex of lines in the entire field. However, that way of approaching the problem makes it difficult to establish why such clear patterns develop (and why there are such evident lines with spaces between them). Faraday took note that filings arrange themselves (or, rather, are prodded) into flower-like curving lines. He imagined a force that traced out invisible lines in the field, which the iron filings reveal (and, with the paper cited above, Maxwell was confirming that a force is transmitted along particular lines).

The great mathematical physicist Roger Penrose, in his enchanting The Road to Reality: A Complete Guide to the Laws of the Universe, says this:

a profound shift in Newtonian foundations had already begun in the 19th century, before the revolutions of relativity and quantum theory in the 20th. The first hint that such a change might be needed came from the wonderful experimental findings of Michael Faraday in about 1833, and from the pictures of reality that he found himself needing in order to accommodate these. Basically, the fundamental change was to consider that the ‘Newtonian particles’ and the ‘forces’ that act between them are not the only inhabitants of our universe. Instead, the idea of a ‘field’, with a disembodied existence of its own was now having to be taken seriously. It was the great Scottish physicist James Clerk Maxwell who, in 1864, formulated the equations that this ‘disembodied field’ must satisfy, and he showed that these fields can carry energy from one place to another. These equations unified the behaviour of electric fields, magnetic fields, and even light, and they are now known simply as Maxwell’s equations, the first of the relativistic field equations. (19)

Newton’s image of gravity, I remarked, pictured gravity as though being emitted by the sun, leaping over space, and acting on the earth—that is the crux of the action-at-a-distance theory. Ampère and the Newtonians believed electromagnetism operated on the same principle—that electromagnetic force acts at a distance (it could just as well act in empty space). Space was empty, a void—and gravity leaps over that empty space to attract a more or less distant object: the Newtonian early researchers into electromagnetism maintained that (like gravity) electromagnetic force can leap over empty space to affect a tangible body. Furthermore, Newton had presumed gravity to be a force that acted instantaneously—the sun’s pull on the earth (at some point in its orbit), and the earth’s response—being pulled from a straight line back to its elliptical path—happen simultaneously; so Newtonians supposed that magnetism and electricity behave similarly. Faraday had a different conception of magnetism’s relation to space: magnetic force flows through space, in curved lines resembling those in the patterns that iron filings make; and force therefore takes time to move through space: action and response (cause and effect) are not instantaneous. Furthermore, the magnet infuses the space around it with force: that magnetized space is what Faraday called a field, and it is shot through with invisible curved lines of force that carry energy from one place to another. A charge influences the space around it. Space is as though energized.

Maxwell’s Theories Found a Cosmology

Alfred North Whitehead (1861–1947), who probably has gone further than any other thinker in outlining the contours of the postmodern metaphysics, wrote his doctoral dissertation on Faraday and Maxwell’s theories. In The Concept of Nature, he notes, “As long ago as 1847 Faraday in a paper in the Philosophical Magazine remarked that his theory of tubes of force implies that in a sense an electric charge is everywhere. The modification of an electric field at every point of space at each instant owning to the past history of each electron [the topic of this section of Whitehead’s book] is another way of stating the fact.” (20) He goes on to remark, regarding objects with which physical laws are concerned (namely, “bits of matter, molecules and electrons”)

An object of one of these types has relations to events other than those belonging to the stream of its situations. . . . In truth the object in its completeness may be conceived as a specific set of correlated modifications of the characters of all events, with the property that these modifications attain to a certain focal property for those events which belong to the stream of its situations. The total assemblage of the modifications of the characters of events due to the existence of an object in a stream of situations is what I call the ‘physical field’ due to the object. But the object cannot really be separated from its field. The object is in fact nothing else than the systematically adjusted set of modifications of the field. . . . From this point of view the antithesis between action at a distance and action by transmission is meaningless. (21)

Here is a somewhat less technical and more compact remark by Whitehead, making a similar point—in the course of this commentary, Whitehead critiques Thomson’s concept of the material æther and offers his own, even more radical conception of the æther—of an “ether of events” rather than a “material ether”:

The point I want to make now is . . . that something is always going on everywhere, even in so-called empty space. This conclusion is in accord with modern physical science which presupposes the play of an electromagnetic field throughout space and time. This doctrine of science has been thrown into the materialistic form of an all-pervading ether. But the ether is evidently a mere idle concept—in the phraseology which Bacon applied to the doctrine of final causes, it is a barren virgin. Nothing is deduced from it; and the ether merely subserves the purpose of satisfying the demands of the materialistic theory. The important concept is that of the shifting facts of the fields of force. This is the concept of an ether of events which should be substituted for that of a material ether. (22)

Faraday, we have noted, conceived of lines of force as like a substance (indeed, as being the only substance): Alfred North Whitehead rejects this, substituting for it the notion of “an ether of events” (23) as an entailment of the “shifting facts” of “fields of force.” In a similar vein, in An Enquiry Concerning the Principles of Natural Knowledge, Whitehead states, tersely, “Time, Space, and Material are adjuncts of events.” Recall, in this connection, Boccioni’s comment about endless lines and currents emanating from our objects, making them live in the environments from which they emanate. Boccioni’s ideas about space and his conception of lines of force can be connected to Faraday and Maxwell’s fundamental cosmopoeic ideas. And since it can be done, it must be done: what is at stake is the nature of space. To conceive of electromagnetism as being similar to gravity is to conceive of its relation to the space it passes through as having no importance and of space itself as almost nothing. To conceive of electromagnetism as being similar to heat is to conceive of its relation to a space into which it radiates as having key importance. Choosing the latter leads one up against a thorny question: what is the nature of this strange, invisible field?

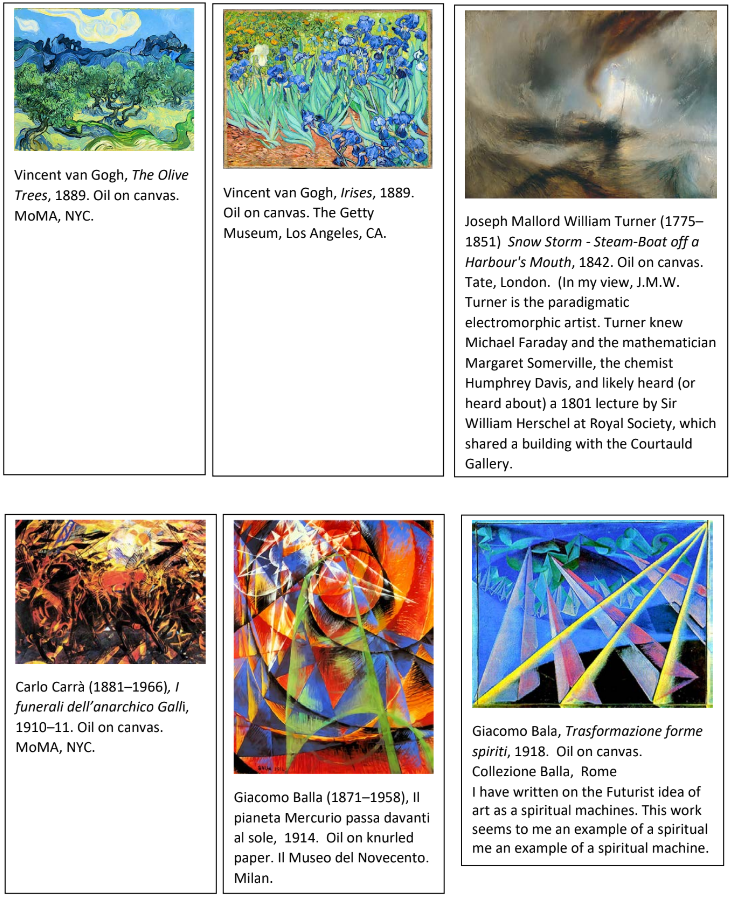

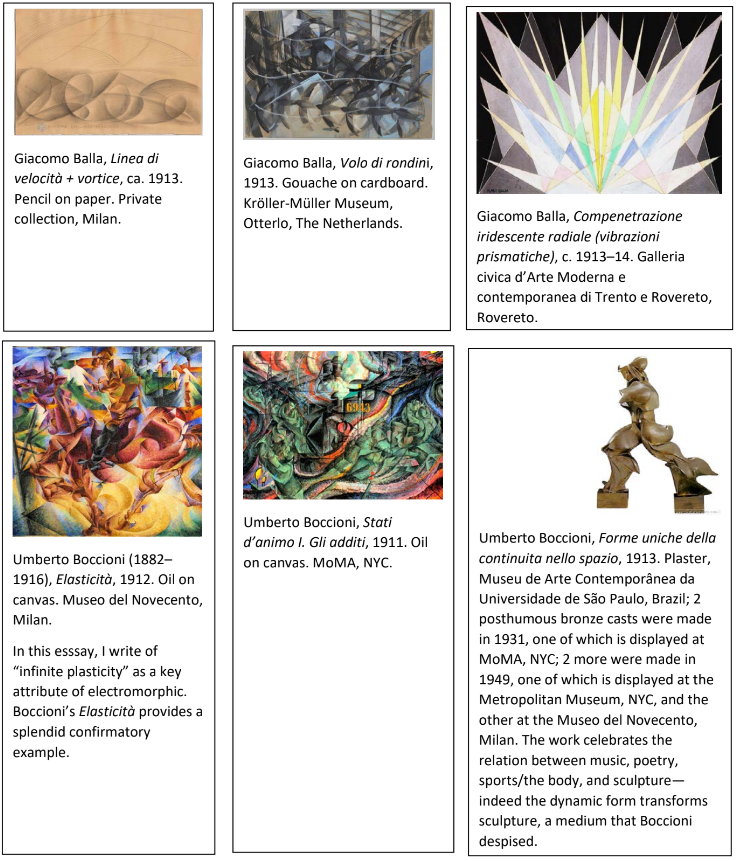

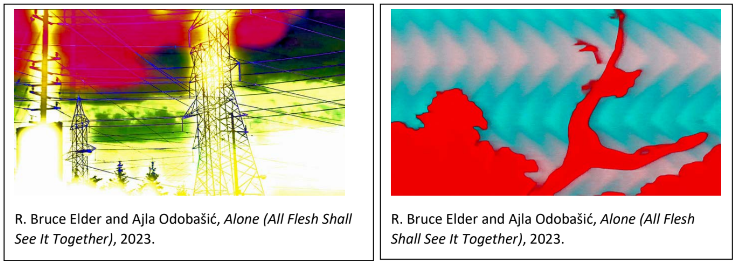

A key to the answer is that interacting magnetic fields exert torsion on each other: they pull one field into another. Boccioni’s Sviluppo di una bottiglia nello spazio (Development of a Bottle in Space, 1912–13) and Forme uniche della continuità nello spazio (Unique Forms of Continuity in Space, 1913) show what happens. Understanding twentieth-century artists’ interests in electromagnetic field effects casts their interest in plasticity into a new light. The impact that African American art had on Europe in the early twentieth century can be connected to the enthusiastic embrace of forms suggesting what Stanley Crouch calls “infinite plasticity”—I did that in Cubism and Futurism: Spiritual Machines and the Cinematic Effect. There I showed that African American art—especially jazz—made African and other so-called “primitive” (unhappy term!) art seem modern, a part of the American century. (24) Jazz and “primitive art” (again, I insist this is an unhappy term!) highlighted that to be modern was to be involved with plasticity. Distortions of form seemed novel, fresh, and potent. But it was not simply the novelty of such plastic interests (evident in “primitive art”) that appealed to twentieth-century artists: an equally compelling reason for the remarkable enthusiasm artists showed for infinite plasticity is that distortions of this sort are common in the electromagnetic realm: Boccioni’s work shows that. So-called primitive art was seen as being postmodern, because it had avoided the error of Newtonianism-Gutenbergism and was already electromorphic, all the while preserving the traditional richness of cultures that had not succumbed to the Western valorization of reason.

A major difference between the Newtonians and the Faradayans is that the Newtonians considered the force of attraction or repulsion on the iron filing particles (to take that example again) as acting between pairs—first, between the south pole of the magnetic and one of the iron filings, then between its north pole and that same iron particle (these computations would be done for each and every iron particle). The space between particles, and the space between the particles and a pole of the magnet, was of no account. Faradayans, on the other hand, supposed every point in that space to be charged by the lines of force. An electric current passing along a wire conductor would affect space similarly—the current would create a magnetic field around the wire, and that magnetic field could form patterns in iron filings, displaying the lines of force created by the current.

The iron filings make the lines of force visible. When there are no iron filings in the area, there is still a magnetic field around the wire, with lines of force. Faraday provided a means for calculating the force of an electromagnetic field on a particle at a given point, not by considering properties of the objects (the magnitude of the charges on them) and of the distance between them (as Coloumb’s law had it), but by considering the number of lines of force in the field around the particle. The pole of a magnet, or an electric current in a wire, radiates a force from what can be considered (for the sake of illustration) a point. As the rays of radiation fan out from the point into space, the distance between the lines of force increases and the number of lines of force in a given area decreases. (It is interesting, given Pound’s remark about algebra queering our geometry, that Coulomb’s law—the older way of understanding the problem—is based on an algebraic/analytic model, while Faraday’s calculation of the force of an electromagnetic field on a particle at a given point is based on a geometric model.) John Clerk Maxwell took Michael Faraday’s geometric intuition and, after developing a new mathematical object, the vector field, worked out its computational implications and applied them to calculating the characteristics of various electromagnetic phenomena. (25) In doing so, he established the science of electromagnetism on a solid foundation and, in the process, proved the accuracy of his friend Faraday’s intuitions. Unfortunately, Faraday did not live to see his science of electromagnetism triumph over that of the Newtonians: he died on 21 August 1867, broken-hearted that he had not prevailed. In 1873 Clerk Maxwell published the two-volume A Treatise on Electricity and Magnetism. Thereafter, electromagnetic space was conceived in Faradayan terms.

Out of Faraday and Maxwell’s theory of electromagnetism, a cosmology emerged—and the earliest truly profound statement of that cosmology is set out in the philosophy of Alfred North Whitehead. For Whitehead, reality was pervaded by a sort of nisus that strives to realize novelty—reality is process, a “perpetual perishing” of what is and the perpetual emergence, through what he called “concrescence,” of a new, short-lived entity/event. The fundamental unit of reality, he proclaimed, is “the ultimate creature derivative from the creative process.” (26)

The conviction that process has priority over things and substances (as process engenders things and substance and determines their characteristics), which Whitehead and Bergson shared, is one that conforms to the electromagnetic metaphysics that rose to prominence in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Whitehead was acutely aware of the sweeping change that was taking place as a new world view, based on ideas about electromagnetism, emerged (and this awareness makes Whitehead an even more crucial figure that Bergson). Whitehead notes: that now “we are in a special cosmic epoch”, and that it is inhabited by electronic entities/events:

Here the phrase ‘cosmic epoch’ is used to mean that widest society of actual entities whose immediate relevance to ourselves is traceable. This epoch is characterized by electronic and protonic actual entities, and by yet more ultimate actual entities which can be dimly discerned in the quanta of energy. Maxwell’s equations of the electromagnetic field hold sway by reason of the throngs of electrons and of protons. (27)

Whitehead had attended presentations by Nikola Tesla (1846–1953) in London (1891) on the topic of “Experiments with alternate currents of high potential and high frequency”—lectures in which Tesla laid the groundwork of his ideas on radio technology. As far as I know, the text of the London lectures does not exist, but that of a lecture he gave on the same topic to the American Institute of Electrical Engineers at Columbia College in New York, on 20 May 1891, does, and it seems quite likely that the lectures were substantially similar. The address at Columbia began with Tesla saying that nature is a most captivating and worthy object of study, and that “Nature has stored up in the universe infinite energy. The eternal recipient and transmitter of this energy is the ether. . . . Of all forms of nature’s energy, which is ever and ever changing and moving, like a soul animates the inert universe, electricity and magnetism are perhaps the most fascinating.” He asked, “What is electricity, and what is magnetism?” (28)