Bárbara Bergamaschi – Let’s start from the beginning. In previous interviews, you’ve mentioned that your passion for cinema was ignited at a young age, when you clandestinely watched western films at the sole theater in your small hometown, Mistelbach. In 1978, you seized the opportunity to participate in a five-class lecture series, held at the Film Museum in Vienna, led by P. Adams Sitney, a prominent figure in American experimental cinema, that conceptualized the famous term “Structural Cinema”. These lectures proved pivotal in shaping your cinematic references.

Could you elaborate on your cinematic upbringing? What steered you towards experimental cinema, despite your allegedly preference for comedy films by Jacques Tati and the Marx Brothers? Why the experimental genre?

Peter Tscherkassky – Well, it’s difficult for me to start anew without revisiting what I’ve already mentioned in other interviews, but I suppose I must do it for the sake of our conversation (laughs).

Regarding watching films, that wasn’t exactly a secret activity. I could see the cinema from where I lived; it was within walking distance. Perhaps that’s why my parents didn’t hesitate to let me go by myself, on a regular weekly basis. While Western movies left a significant impression, they were not the only genre I was inclined to. It was cinema in general which was my early passion within the realm of art.

I vividly recall my concerns when I was transferred to a Jesuit boarding school in Vienna at the age of eleven… One of my main worries was missing the Sunday afternoon screenings in my hometown Mistelbach, as I had to return to the boarding school by five o’clock. I was delighted when the schoolmaster showed us around and revealed that they had a cinema, too. That brought me immense joy.

BB – Inside the boarding school, there was a cinema theater?

PT – Yeah, it was a massive 19th-century building, considered one of Austria’s elite schools, so to speak. Despite being a wealthy institution, attending wasn’t solely reserved for an economical elite, I mean, my family was not rich. They would lower the price for talented students, that was the primary criterion for admission. But, as I said before, my interest in cinema persisted over the years, alongside a growing appreciation for literature, primarily. Initially, my aspiration was to pursue journalism, perhaps even become a writer.

As for cinema, I wasn’t drawn to the commercial aspect of filmmaking, which always requires substantial budgets and teamwork. You would have to be a team player, and actually once I contemplated applying to the DFFB, the film school in Berlin. Although I never followed through, the application process intrigued me; you had to submit a script to even be considered for the entrance exam. They purposely selected quite uninteresting topics to assess applicants’ creativity and adaptability. Well, I shouldn’t call them stupid, but…

BB – You mean themes were basic, rather straightforward?

PT – Well, for instance, in that year it was about love. The question was: “How does one portray love in cinema?”. And the result was an early film called Liebesfilm, which I made in 1982. So, as you can see, that’s probably why they never considered me for the film school (laughs).

A one second shot of the two heads of a couple approaching for a kiss is repeated 522 times; that brief movement is continuously sped up to double speed. At the same time the perforation hole and the edge of the frame above is shown.

Nevertheless, that was the outcome of my flirt with DFFB.

By that time, I had already created several films; Liebesfilm wasn’t my first endeavor, as you know. Anyway, the notion of working with a large crew, budget, and all that paraphernalia never crossed my mind. I simply adored cinema but deemed it beyond my reach. Then came the P. Adams Sitney lecture series; until that moment, I had no idea and never heard about the existence of avant-garde filmmaking.

BB – Did you have the idea for Liebesfilm’s script before watching P. Adams Sitney’s lecture? Were you already in experimental realm without knowing the genre?

PT – No, no, Sitney was in January 1978, four years earlier, when I was 19 years old.

Let’s backtrack a bit on our timeline. I cultivated my interest in film, wanting to be involved somehow, but not necessarily as a director, screenwriter, or cameraman in a classical division of labor in commercial cinema. Then P. Adams Sitney came along and presented me with the possibility that I could work with film like a fine artist, a painter or a writer. That was the turning point. I sat there, five days in a row, watching the screen, and suddenly I knew what I wanted to do with my life.

BB – It seems like it was a significant moment for you. I brought up the Western genre because I came across an interview where you mentioned sneaking into the balcony of the cinema as a child, perhaps around the age of 8, to watch The Good, the Bad and the Ugly secretly. I found that story quite intriguing, specially because Western movies seem to have left a lasting impression on your work, appearing in films such as Instructions for a Light and Sound Machine and Shot – Countershot. Could you elaborate on that childhood memory and experience, and how it might have influenced your later work?

PT – Yeah, that’s correct, there was this experience. I was indeed underage, but it wasn’t during my childhood years in Mistelbach, it was during teenage years. The Good, the Bad and the Ugly wouldn’t have been shown at the three o’clock screenings there. Instead, they would typically show Karl May films at that time. Karl May is a writer who also worked with the Western pioneers imagery. He is one of the most renowned popular writers in the German-speaking world, having sold over 200 million copies of his books. He wrote extensively about Native Americans and the Middle East, creating characters and stories that captivated readers. His Winnetou series, in particular, left a significant imprint on many childhoods, including my own.

As for The Good, the Bad and the Ugly, that was an experience from my time at boarding school when I was perhaps around fourteen years old. It was being screened at a Viennese cinema, and despite being underage, I was allowed to leave the school grounds on Sunday afternoons. So, if we didn’t return to our hometowns, we had the option to go to the cinema. I remember trying to buy a ticket at the box office, but they refused to sell me one. But the owner told me to wait. Once the doors of the main auditorium were closed, he led me onto the otherwise closed balcony, without a ticket. Of course, I had paid for my seat, and now I found myself sitting up there all alone, experiencing The Good, the Bad and the Ugly. It was truly an unforgettable moment.

BB – You seem to have a preference on English speaking films that are either classical canonical or old B-movie horror/porn or even advertising commercials, as the archival base for your films. For instance, L’Arrivée was crafted using a movie trailer taken from Terence Young’s Mayerling, a feature film with Catherine Deneuve as leading role. However, you rarely incorporate footage from renowned classical Austrian filmmakers, like Georg Wilhelm Pabst or Fritz Lang, for example. Austria has a rich cinematic tradition, so I’m curious, was there a desire to work with this North American imagery material? Or perhaps there were legal constraints preventing you to have access to this great Austrian films? Were the distributors of their films not open to collaboration?

PT – So far I had no access to any of those prints! And, you know, nobody ever gave me permission to use any of the footage I incorporate… I simply take it. Especially in the early years, I stumbled upon raw footage by chance, and after watching it several times, ideas would either come to me –or not… Sometimes friends would ask me, “Would you like to have access to that print?” or someone like Nicole Brenez, who has always tremendously supported my work, would say, “I found a copy of King of Comedy on eBay, do you want it?”. Friends would come across old prints that were slated for destruction, and instead of being destroyed, they were offered for sale and handed over to me, which, well, isn’t entirely legal (laughs).

Anyway, I worked with what I received by chance and never actively sought out specific films. Although, I should say “never” is too strong a word. In the case of Train Again, I wanted to include quotations from classic avant-garde films I am fond of, so I transferred them from DVD to analog film to be able to copy them in the darkroom. But these instances only account for a few seconds of footage.

BB – Since you mentioned your last film Train Again, I was curious, are there any CGI or digital special effects on it? I was unsure when I watched it on the cinema. I noticed footage from a recent film that seemed to have chroma-key effects…

PT – Regarding Train Again, there are no digital manipulations. I never do that.

The scene with the exploding train comes from a movie trailer. I used two trailers, gifts from my wife, the filmmaker Eve Heller. Each maybe two minutes long, one from the film Lone Ranger with Johnny Depp, and the other one was from a disaster film, Unstoppable, with Denzel Washington.

BB – Let’s get back on the chronological ‘track’ of your personal story. Shortly after attending the P. Adams Sitney lectures, did you decide to enroll in a philosophy major at the university? And was it around that time that you purchased your first Super 8 equipment, right? Then, later on, you established your P.O.E.T Picture Production company, which has become your trademark or production house to this day.

You then went on to create your first films: Kreuzritter (1979), Portrait (1980), Rauchopfer (1981), Aderlass/Blood-Letting (1981), Sechs über Eins (1982), Ballett No.3 (1982), Partita (1982), Liebesfilm (1982), Erotique (1982), Urlaubsfilm (1983), Miniaturen (1983), and Ballett 16 (1984). However, only five of these films are currently available, the last four I mentioned and Aderlass, which are accessible on DVD released through sixpackfilm’s DVD-label “Index”. I am very curious to learn why we can’t view your earliest films. Are the original Super 8 films cartridges lost or are they “banned” youth films?Or can we expect to see them in the near future?

PT – No. It’s just that I don’t consider them strong enough or good enough. I mean, the very first film Kreuzritter is interesting, but it’s so blasphemous that I might run into legal troubles. However, it has been shown in public several times. But making it available online or on DVD would be more complicated…

BB – Well, considering this theme of blasphemy, in the five youth films I mentioned, we see an oscillation between two influential currents in which you consider yourself an heir. On one hand, there is structural filmmaking, with certain mathematical premises, such as films by Kubelka and Kren–influence we can see in Ballet 16, Liebesfilm, and also Manufraktur and Motion Picture–and, on the other hand, there are more visceral action films akin to the Viennese Actionism movement, such as Miniaturen–a film created in collaboration with a collective of artists. There is also this Actionism “echo” in Aderlass, Erotique and Urlaubsfilm. I know that Rauchopfer, despite not being available for viewing, was dedicated to Hermann Nitsch, right? So it seems to me that this delicate balance between intense bodily sensory experiences and structural commentary within the medium has become your distinctive hallmark, which has been refined over the years. Could you comment on this dual influence?

PT – Most of my films are a combination of abstraction and figuration. I’m not sure how important structural filmmaking remains for structuring my work. In the case of Outer Space, it’s clearly there; there are transitions between segments where I use simple mathematical structures, and some frame counting is involved. But, as I’ve mentioned in interviews, I regard myself as a narrative filmmaker. All of my films have a tiny little story, even Train Again, which one might see as an exception to that rule. Even that film has a tiny narrative structure, although that doesn’t exclude the possibility of hidden mathematical structures as a basis. It doesn’t exclude it at all, but mainly I’m interested in narration as a structuring principle. And that has its own rules, it follows a narrative logic.

Dream films are the easiest task. To pick up a dream logic, which is a logic without logic, allows you to float around within the images while still having a narrative mattress to build “on top of it”.

BB – It’s always a kind of progression acceleration in your films, right? Train Again begins slowly…

PT – Yes, it has a classical structure. Always. It starts with an overture and somehow a climax, and then a chill out. And that structure is thousands of years old. And I don’t regard myself as important enough to question that. As a matter of fact, what I dislike in experimental filmmaking or avant-garde filmmaking, maybe “dislike” is a too strong word, but I have my reservations, are those films where there’s one basic idea executed for a certain amount of time, and then it stops, and it could have stopped a minute earlier or two minutes later, and it wouldn’t make much of a difference. At least, you wouldn’t say as a spectator, “Ah, there’s something missing”.

Instead, I love classical narrative structures, and I continue to hold onto it. And, in between, there are mathematical structures based on the ideas of serialism or structural filmmaking. But that’s not the core of my films. It’s not my main goal to execute such a structure, making it the main content of the whole work. No, the main content of my film is wrapped into a tiny little narration.

BB – In some way, your films are always about destruction, isn’t it? It seems like there’s always a self-destruction. Or, to rephrased it: there is always a narration on destruction. So, in that way, it’s similar to Vienna Actionism, as their performances also were investigations on the theme of destructing their own bodies or showing the visceral mechanisms of their body…

PT – I agree, but I wouldn’t call it destruction. I would call it a revelation. As if the films make something visible. I compare myself–speaking of my early influences as a kid watching films and loving those films–to a kid who has a favorite mechanical toy. The kid winds it up and then it wants to find out how it works. It opens up the toy and destroy it by trying to understand how it works. And I’m opening up something, but instead of just destroying it, I reveal something else, I reveal a potential that has been there, but was hidden, so to speak.

If you take Train Again with its Cubism-like or Jackson Pollock-like images towards the end–somehow it was all there before, but it needed someone to “destroy it”, to break it all apart and combine it in a new way. And that’s a respectful way to deal with found footage. I aways approach my footage with respect, it’s like a cooperation between me and some other artist. Just in the case of Coming Attractions, which I see as a comedy, I made fun of some of the models who are acting, or should I say “non-acting”, but still the footage itself stays intact, so to speak. Or, in the case of Train Again, it starts with the train. We see the train coming, it goes by, and then it vanishes again in the distance. That original scene was really badly filmed. Simple as that. And maybe, you might say, directed by a director who was simply not up to snuff. But I tried to transformed it into something good (laughs). So again, it’s kind of a homage–with respect to whoever shot it in the first place.

BB – Although in many interviews you mention your admiration for Picasso and Braque, particularly in their synthetic/analytical cubism, it seems to me that beyond the handmade bricolage process with pre-existing materials (similar to the gesture of pasting newspapers onto canvas), there is always a very strong charge of eroticism in your films.

My first thought after watching your films for the first time, was that you would actually be a signatory to surrealism–because, not only, one of your films refers to the surrealist method of the cadavre exquis, and there are these direct quotations of Man Ray in Dream Work, but also because I remembered the famous quotation of Breton “Beauty should be convulsive (like a seizure), or it wouldn’t be beauty”. And so I thought that maybe your approach to surrealism was more related not to the figurative surrealism (such as Dalí and Magritte) but to the violent aspect of surrealism, maybe more aligned to Bataille, for example. Bataille builds his thought process about Eroticism right on the edge of an abyss between Eros and Thanatos, he would say, and I quote him now:

“Between one being and the other, there is an abyss, there is a discontinuity (…) there is no possibility of overcoming this first difference. This abyss is deep and we cannot bridge it. It turns out that we can in common feel the vertigo of this abyss. It can fascinate us. That abyss in a sense is death, and death is dizzying, fascinating.”

Could you comment on this erotic and violent charge in your films and if the surrealists are a reference for you?

PT – Fittingly, as we are talking about surrealism, I’d say, on an “unconscious” level, it might be (laughs). But cubism contains so much more as an investigation and a ludic approach towards reality, towards our perception of reality. Whereas surrealism is kind of limited in its possibility, and in a way exhausted through the poster and pop culture for teenagers, especially Dalí–which cubism is not at all, I would say. But yes, you are perfectly right, there are many allusions to surrealism in my films, especially in Exquisite Corpus and Dream Work.

And the connection between erotism and death as Thanatos. I simply don’t share the interest of Bataille in death, and I do not necessarily agree with the connection he sees between eroticism and death. It has more to do with an orgasm as a dissolution–everything vanishes, so to speak, in the moment of orgasm, and you might say some of my films offer a kind of visual orgasm.

BB – But that is interesting because in French the orgasm is called “petite mort”,“little death”, so there is a connection right? Bataille suggests there is a connection or correlation where the divine and the sexual experience can converge. The orgasm would be a moment of dissolution and fusion with another being, a experience of “non-continuity”. This “little death” could be also be found within religious epiphany and the communion with God/Christ. Bataille further argues that sacrifice, divinity, and sexuality are interconnected and intertwined, a perspective that resonates with the themes in your films, suggesting also they serve as rituals of love and “communion” with cinematic experience itself.

PT – What I try to convey with my films, as many other filmmakers of course, is to create an experience which cannot be translated into spoken words, which cannot be translated into any other language. And that’s very interesting when that wordless, speechless experience happens. And that is something which connects with death, of course, which is the ultimate experience, but also with the orgasm again. And so it would be somehow a contradiction in itself if I start talking now with words about that unique experience (laughs).

BB – In interviews, you’ve positioned yourself as part of the third generation of Austrian avant-garde cinema, distinct from predecessors who had already explored “radical” approaches, that ironically created a “tradition” in subversion. Your generation, alongside other filmmakers that are your contemporaries (like Martin Arnold and Gustav Deutsch), embraced found footage and archive as a new cinematic language. However, you’ve recently expressed concerns about the decline of analog media in favor of digital formats, a sentiment shared by many artists globally. Would you consider this shared concern a symptom of our era?

PT – The genesis of modern art lies in exploring the specific possibilities of each medium. That approach was a consequence of the era of Enlightenment. That period saw the spread of rationality across all parts of society, leading to shifts in religion, politics, economics, and the arts. Artists began to question how they could uniquely utilize their materials, marking a rational turn in their approach.

Analog cinema, rooted in analog footage, offers distinct artistic possibilities compared to those of digital mediums. Working with analog allows for a handmade, low-tech, and tangible quality that cannot be replicated digitally. For me, to abandon analog for digital would be to work with a completely different medium, or a different “animal”. I strive to create works that show the unique qualities of analog and resist digital homogenization. Despite the increasing digitalization of cinema, I remain committed to preserving the essence of analog filmmaking. Again: if I would transition from analog to digital it would mean switching over to a completely different medium. And I always try to create a handmade atmosphere that could not be replicated with a computer.

But, of course, the situation for analog filmmaking is dire. When I made Train Again there was not a single film lab left in Austria, so instead of using workprints I had to watch with my original negatives on a moviescope. After completing the film, it had to be printed in Paris. And many festivals are no longer capable of showing analog cinema. When Train Again premiered at the Cannes Film Festival in the Director’s Fortnight section, it was the only 35 mm print in the entire festival! Everything else was digital.

BB – Do you truly believe it’s impossible to convey certain aesthetic experiences digitally? What makes analog unique? Isn’t there a risk of this stance being perceived as nostalgic or excessively romanticized? Unlike Peter Kubelka, you don’t hold a purist position and allow your films to be digitized into DVD format. Many of your films reached me, living in South America, through the Internet or DVDs. My first exposure to your films was on YouTube because it’s challenging to access them in movie theaters in Brazil. So, in a way, isn’t the digital format beneficial for distribution?

PT – Digital undeniably has its advantages, no question about that. But the process of creation, when you focus solely on that aspect, differs entirely between analog and digital cinema.

BB – Yes, I mean, it was really a completely different experience when I saw Train Again at the Vila do Conde Festival in a movie theater compared to seeing on my laptop. The organization of the festival mentioned you didn’t allow the film to be streamed online (the festival was hybrid format that year due to Covid-19 restrictions). I preferred seeing it in loco because I wanted to experience it physically, and indeed, it was a much more intense experience. However, if it weren’t for digital, I wouldn’t have been able to discover your films. So, in a sense, you’re already navigating hybrid territory anyway.

PT – The key is to recognize that when you view it digitally, whether on a DVD or online, you’re not seeing the real thing. Watching on YouTube, for example, doesn’t capture the true essence. The problem arises when people discuss it online, leaving comments as though they’ve experienced the genuine thing, which they haven’t. Essentially, it’s like reading a libretto of an opera but not witnessing the live performance.

BB – Speaking on the materiality and working process, I’ve read about how you do it, but it would be nice to physically see the overlapping of film and the laserpoint flashlights. I wish I could take a look at it.

PT – Yeah, it’s quite simple. I’ll show you… (he gets up to get the flashlights) This is a laser pointer, and you can see how tiny the segments are which I can copy. You can see how I can use it to copy and print really tiny details.

BB – It’s like pointillism.

PT – Yes, it’s like pointillism, and it’s painting with light. It’s like using a brush. And now this flashlight has a softer light, and a bigger light spot, but you can still copy only parts of the image by using a mask.

BB – Do you use the positive copy first as a base, like, for example, in The Entity? Do you use the positive and then the negative?

PT – No, when it’s being printed the positive becomes a negative, and that’s it. I create a negative.

BB – So you have to work with at least two copies of the film?

PT – No. The positive becomes negative, and then the negative is the end result which is printed to become positive again.

BB – So you have a final master negative?

PT – Yes, I create a so-called negative, which is the basis for all copies, all prints, which are all positive again.

BB – I thought it was five or six, seven positive copies on top of each other, like a sandwich.

PT – I copy the different shots from the found footage one after the other, not at the same time. I print one layer of images after the other, not as a sandwich. Just one by one. Five or six or seven layers, one after the other, and through that process of melting and collaging it all becomes one unique negative.

BB – And the flashlights, are there three different sizes, really like brush strokes?

PT – Yes, I use approximately ten different flashlights and lasers.

Peter Tscherakssky with his flashlights (Bárbara Bergamaschi).

BB – Speaking about the issue of materiality of film, it reminded me of the debate around the objectification of the female body, which I consider very present in your films, in a particular way. In 1975, Laura Mulvey published the seminal text for gender and feminist studies in cinema “Narrative Cinema and Visual Pleasure”. Based on psychoanalytical readings of Lacan and Freud, Mulvey proposes that the classic Hollywood system of representation is supported by an unconscious patriarchal scopic logic: female movie stars are a corporeal spectacle, objectified, something to “be looked at”, while the male protagonist is the “bearer of the gaze”, in charge of conducting the narrative (what she calls the “male gaze”). Would you say your movies address this male gaze in some way, criticizing or deconstructing it? Could you comment more about gender debate in your films?

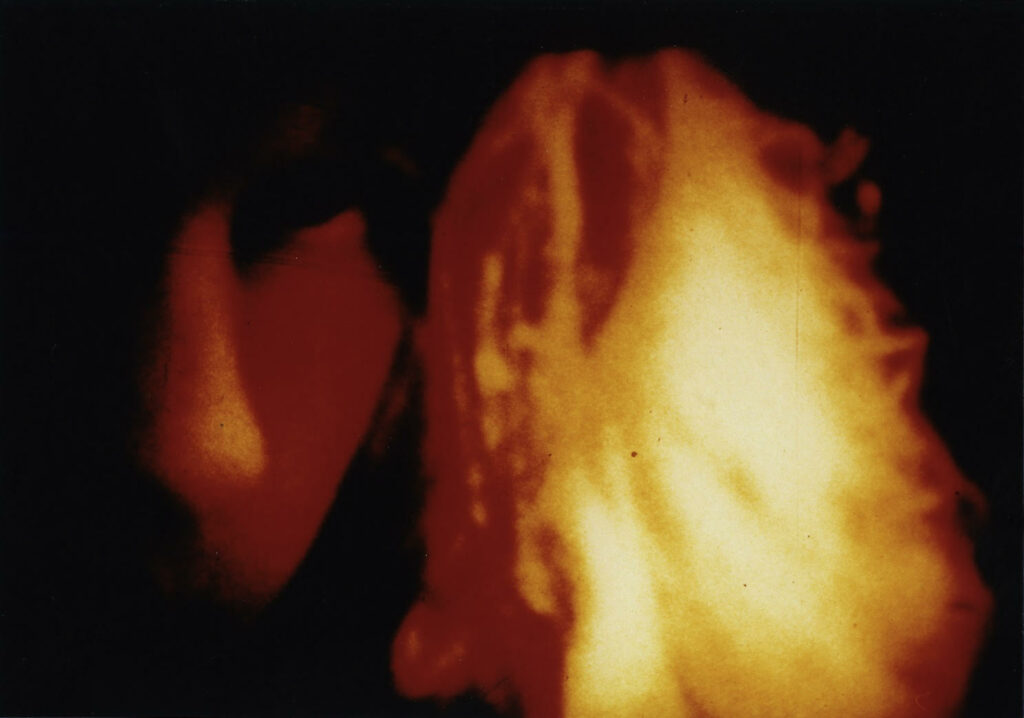

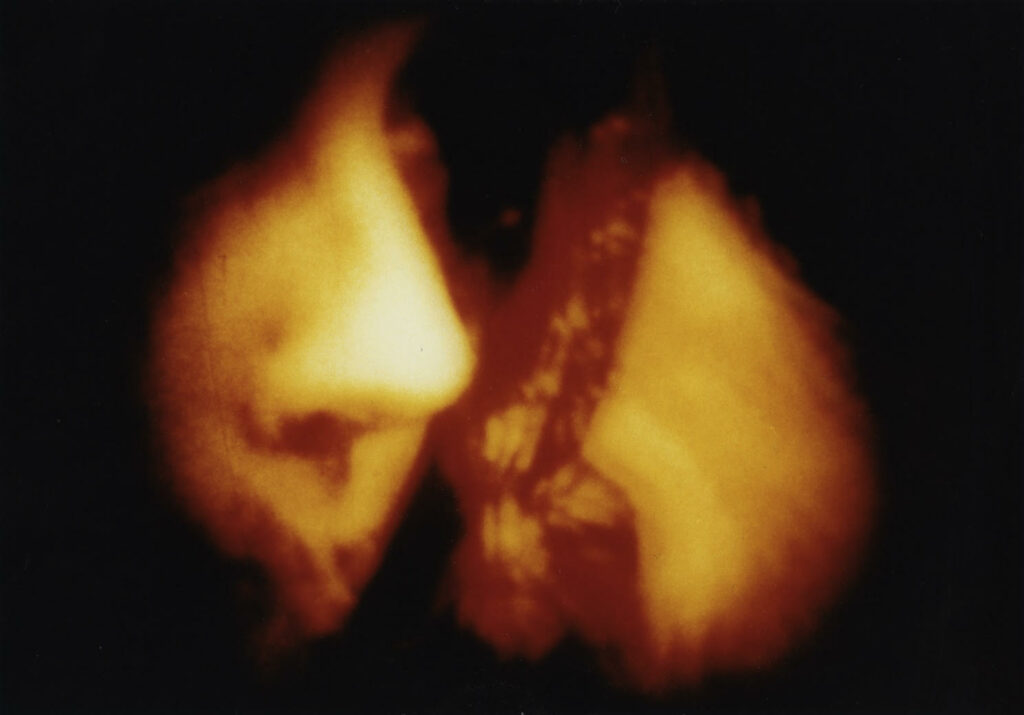

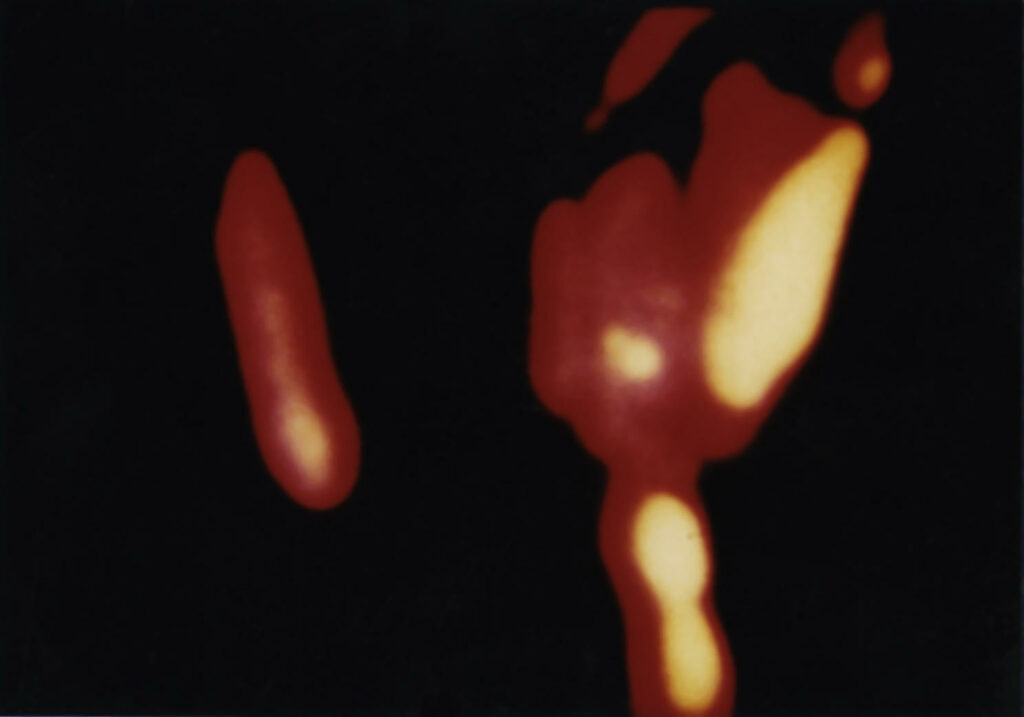

PT – Well, in the case of Urlaubsfilm, I would say it starts off with the classical male gaze, the voyeuristic gaze, and that it is replaced step by step and destroyed in favor of the material, the film medium itself. There is a one minute sequence of the beautiful woman as basic material, and that minute is re-filmed, again and again, until the image has become totally abstract.

Continuous series of increasing abstraction in Urlaubsfilm, 1983. Courtesy of Peter Tscherkassky.

Tabula Rasa is a tricky thing. It’s available on DVD, but it is not being distributed as a print, a long story. All that film is based on ideas of Christian Metz and Jacques Lacan, so I deliberately used the naked woman as the object of the classical male gaze, which forms the basis of Christian Metz’s theory.

My point is that a film has to be figurative to fulfill the conditions for Christian Metz’s theory to function. As soon as you take away the figurative aspect and replace it with an abstract image, his theory of the self-identification of the viewer as the supposed creator of the meaning of what is seen on screen fails. So, Tabula Rasa is nothing else but a twenty-minute-long exercise in trying to make that transition from the classical figurative object of the male gaze into something of its own: into pure light, into pure form-and beauty–, as I think it is an extremely beautiful film. Forgive me if I call my own work like that (laughs).

And, of course, I try to problematize, to put into question the male gaze by showing myself with the camera and showing the act of filming. At a certain moment, you see my hand, the shadow of my hand trying to grasp and to hold on to the “object”, the woman, which I see, but it vanishes. It disappears into abstract forms of light. Tabula rasa starts with complete darkness, followed by a long opening sequence as kind of striptease: the slow transition from pure abstract forms into something you can recognize, abstract shadows and light slowly become figurative. And then follows the long process of falling back into pure, white, abstract light. So, we have the two poles of cinema: darkness and light, and in between we see what can be formed with those meanings of darkness and light.

I thought of that film as a sort of counterargument to Christian Metz. Metz never understood or accepted avant-garde or experimental filmmaking, he always rejected it, yeah, “this is nothing”, because he needed to deny it for his theory to work, which functions only with regular, classical, industrial cinema. That’s why, maybe on an unconscious level, he rejected avant-garde filmmaking. His theory cannot be applied to experimental filmmaking. And that’s what I wanted to show with Tabula Rasa. So, in that sense, that’s why I used the semi-naked woman as the main object for the male gaze and then problematize it.

Outer Space is the most important example within my oeuvre, where I try to subvert the intention of the original film to show the woman as a victim. Have you seen Sidney J. Furie’s The Entity?

BB – Yes, I did.

PT – Maybe you remember that in the end, when she leaves the haunted house, at the very last shot when she gets to her new house, you hear the ghost saying: “welcome back, cunt”. So, somehow, he wins. He stays there and she simply is defeated…

BB – A really misogynist ghost…

PT – Speaking of Jacques Lacan with his concept of the “mirror stage”, and Christian Metz, who compares the mirror with the screen, in Outer Space, it’s a mirror that the actor destroys, to free herself. Of course, there was that shot of her smashing the mirror, which was ideal for me. And maybe, maybe it was intentional by Sidney J. Furie that whole scene of that mirror destruction, even though I doubt he was familiar with concepts of Metz/Lacan, but it was ideal for my purpose. She smashes the mirror and after that the whole image dissolves and sets her free. In the end, she is the one who has the Gaze and she is looking at us, piercing the fourth wall. In The Entity, there are exactly six frames where she is looking through her bathroom mirror straight into the camera. When I discovered those outstanding six frames, I knew that would be the end of the film. With my frame-by-frame printing technique, I repeated those six frames over and over and over again, so in the end she is no longer the object of our gaze, but instead now she is the bearer of the gaze, staring at us, and we are the object of her gaze!

BB – That’s interesting because you said that it ends in pure light, but L’Arrivée also begins with pure white and ends with nothing. Additionally, in your film Instructions for a Light and Sound Machine, you also appear in the image, and, in Tabula Rasa, your image appears while filming. There is always a circular movement: you being seen by the film and the film looking at us, creating this circular gaze.

PT – Especially in Dream Work, where you see my hands moving and turning the film strip, which we see at the very same time in double exposure, so it reveals me as the filmmaker who is behind all of that. And as soon as the actor wakes up, she laughs at me, after she had been tortured with the superimposed needles and pins. Here, too, she is being put in a position where she is the one who looks and sees the hands of the “creator”–my hands, which I had filmed with Super 8 and transferred to 35 mm, so I could use it in the darkroom. Again, she is being put in that position of subverting her role as a victim.

BT – I have the impression that you were criticizing, or playing with the changing roles of the classical Hollywood portrayal of women. I would like to focus on irony in your films. I perceive that mostly every one of your films has this hidden irony and iconoclastic sense of humor.

For example, Shot-Countershot is, for me, a really hilarious movie. It’s like a gag, a punchline, super economical in its means. I see it as a filmic trap where the découpage of narrative cinema, or using the technical jargon, the raccord turns against itself. That also reminded me, once again, of the surrealists’ playfulness with “language”.

PT – This is my affinity with the Marx Brothers, Jacques Tati, and Billy Wilder. I love comedies…

L’Arrivée, for instance: I see my train like the Lumière brothers’ train, that arrives and brings us cinema in 1895. And cinema brings all that action and violence, which is symbolized in the crash of my train, with the footage crashing on itself. And cinema brings laughter and eroticism as well. So, L’Arrivée demonstrates in a nutshell of two minutes those main contents of narrative cinema: violence, action, excitement, laughter. And eroticism, as Catherine Deneuve and Omar Sharif kiss each other at the very end, the happy ending. After all the disaster of the crash, Deneuve gets picked up and kissed by her lover. Also in Exquisite Corpus we have that happy ending. We see a woman sleeping on the beach and then we experience her dream, and, in the end, she wakes up again and she smiles–it was only a dream…

Coming Attractions, too, is full of irony and jokes.

BB – In Coming Attractions, you appropriate footage from advertising to reveal the avant-garde “side” hidden in publicity. This again reminds me of the Dadaist gesture of détournement or the idea behind the ready-made–re-signifying things that already exist rendering new meaning to them. Also avant-garde artists generally criticize the transparency of discourse in commercial media.

PT – Exactly. The film was made with rushes from unfinished commercials, just the unedited footage for advertising. Manufracture was based on finished commercials, but Coming Attractions uses only raw footage, the footage as it came out of the camera.

B: And Kubelka, your “master”, also did a lot of advertising for beer and for other enterprises, right?

PT – Indeed. In his film Poetry and Truth, Kubelka also used unedited footage for commercials. Adebar was originally made for a cocktail bar of the same name, and Schwechater was an ad for a beer called Schwechater. Arnulf Rainer was commissioned by Arnulf Rainer to be a film about, well, Arnulf Rainer (laughs)… It ended up being something completely different, which is why many years later he made Pause, which truly shows Arnulf Rainer; that’s a film which I don’t understand, simply said… (laughs). There is also Unsere Afrikareise, another film which was commissioned by people who wanted a documentation of their hunting and killing in Africa. He made total fun of them. But he told me that after his film they stopped killing animals and changed to photo safaris.

Bárbara Bergamaschi

Vienna, 18th November, 2021