Ambiance-Palimpsest

A palimpsest is by definition a parchment on which writing has been partially or completely erased to make room for another text. It can also be defined as something that has a new layer, aspect, or appearance that builds on its past and allows us to see or perceive parts of this past: most of what we actually see when we view any culture is a historical palimpsest, with traces of former times (Fig. 1).

André Corboz, among others, introduced the term palimpsest in urbanism in 1981 in his article Le territoire comme palimpseste. His work has been revisited by Sebastian Marot in relation to the interest in memory and heritage that appears in his PhD thesis Palimpsestous Ithaca: un manifeste relatif du sub-urbanisme. Thanks to their work, the term palimpsest has become a metaphor that introduces the temporal dimension and conceives the city as a result of continuous temporal stratification.

In 2004, I tried to introduce the term palimpsest in the field of architectural and urban ambiance studies, which was the main research focus of my PhD thesis: Vers une écologie sensible des rues du Caire: le palimpseste des ambiances d’une ville en transition, which I defended in the Equipe Cresson – Ambiances, architectures, urbanites. Laboratoryat Grenoble School of Architecture. In fact, temporality is one of the relevant criteria in the constitution of an ambiance, since the latter is defined as: “a qualification of space-time from a sensory point of view (Thibaud, 2007). The notion of ambiance-palimpsest shows how an ambiance, despite its fragile nature, unfolds a certain temporal depth, and it reveals the different sensory traces that continue to reconfigure the sensory experience of urban life today.

I have chosen, as a case study, Choubrah, a popular district located to the north of Cairo. In order to understand the evolution of its ambiance and to unfold the temporal complexity of the district, I solicited many types of representation of the city: I searched for the city of the past in urban plans, photos, travel diaries, documentary films and the cinema.

Here, I will focus on the cinema as a resource that lays out the former ambiances of the city. The keen interest in the Cinema in this theoretical framework lies in its nature as “redemption of reality” (Kracauer, 2010). It records and describes the everyday life of the city, thus becoming a fundamental source with which to capture and trace the urban ambiences of the city of the past in its evolution and permanence. Moreover, we should note the extent to which the Egyptian cinema has flourished, and acknowledge the role it has played in representations of the Egyptian territory in different disciplines, such as sociology, anthropology and urbanism. The Egyptian cinema has maintained its luster till now, despite the ups and downs in its evolution during the last century.

Choubrah, a popular district but …

Hây ch’âby: a popular district! This term embeds in Egyptian colloquial language a specific imaginary: it signifies a modest, informal, poor atmosphere, mixed with touches of misery and decay. Despite the dominance of these traits in the ordinary experience of Choubrah the representation of the district in the cinema reveals pale vestiges of earlier atmospheres: names, palaces, clustered greenery and splendid boulevards.

Today, Choubrah is one of the densest and most populous districts of the capital. It is clearly delimited by railway lines to the east and the Nile to the west. It is a typical place, symbolizing the features of popular life. Its inhabitants belong to a middle class descended from a well-educated class or Afandia as is it called in the colloquial Egyptian language. I will try to define the meaning of a popular ambiance of this district as represented in films and constructed in time, and will highlight its origins as well as its originality.

Working on the cinema as a representation of the city of Cairo, we cannot ignore the particularity of the Choubrah district and the role it plays in films and novels as representative of specific aspects of the city in its evolution.

A spatio-temporal sensory journey in Choubrah through cinema

Seven characters, in six films and television series, shot in Choubrah – Cairo, tell, through their daily experiences, different places and moments in the history of the district: Laila, in Laila, The Girl from the Country (Leila, bint el rif), by Togo Mizrahi (1941); Laila, Daughter of the Poor, in Laila bînt el foukara, byAnwar Wagdi (1945); Mahgoub, in Cairo 30 (Al-Qahîra 30), by Salah Abou Seif (1966); Maria, in A Daughter of Choubrah (Bînt men Choubrah), byGamal Abdel Hamid (2004), borrowed from the novel Ghanem, 1986; Om Sami and Loula, in Choubrah Roundabout (Dawärän Choubrah), by Khaled Al Haggar (2012); finally Dalida, in Dalida, by Lisa Azuelos, 2017.

These films had been shot in Choubrah in two key moments: the first during the 1930s and 1940s and the second at the beginning of the new millennium. By decoding the different elements contributing to the ambience of these films (sounds, gestures, spaces, movements, etc.), I will undertake a spatio-temporal urban journey in this district.

A village

A scene of the sky where the branches of camphor trees meet, the camera slowly moves down to show wide agricultural fields; a donkey-drawn carriage is driving along a small street between clustered trees that constantly hide the carriage. The camera approaches a young woman dressed in Egyptian peasant style: a jilbab (long dress) with a long black veil. She sings while strolling through the green fields where she encounters farm animals. She stops and sits at the edge of a water wheel Shaquia.

The camera then shows a panoramic view of wide flat agricultural land delimited at the far horizon by palm trees and the outline of a village. The camera turns slowly: things are too calm where nothing happens. The camera crosses a water canal traversing the agricultural land. The scene ends with a young woman walking along the canal and carrying a carpet on her head.

Laila, the Girl from the Country (Leila, bint el rif), Togo Mizrahi (1941).

Laila, the Girl from the Country is a film that represents the difference between rural and urban life during the middle of the 20th century. The two main characters of the film – Laila who lives in the countryside and her cousin Fathy, a doctor who lives in Cairo after finishing his studies in medicine in London – are forced to get married. Through the story of their marriage, the different scenes of the film show the contrast in lifestyle between Cairo and the countryside (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2

In his book Cairo streets and stories, Hamdi abou Galil identifies certain streets of the city as carriers of a social and urban memory. He dedicated a chapter to Choubrah, in which he documents a meeting with Farouk Abdel Kader, a writer and an inhabitant of the district. The latter’s words constitute an important testimony concerning the major transformations in this district, as seen from the point of view of daily lived experience, during the second half of the twentieth century.

Farouk Abdel Kader says that Choubrah, thanks to its proximity to the city, was chosen to represent the rural ambiance in the cinema in the 1940s and 1950s. He explains that getting out of Cairo to the countryside means going to Choubrah and its agricultural fields. In his description, he points out a specific village in Choubrah: Minet el Sirg, where parts of the film Banat el rif (1945) were filmed. In the film Leila bent el rif, shot in almost the same period, we see a young woman walk through the agricultural land of Choubrah and we see the fertile land and the fields with their intense greenery.

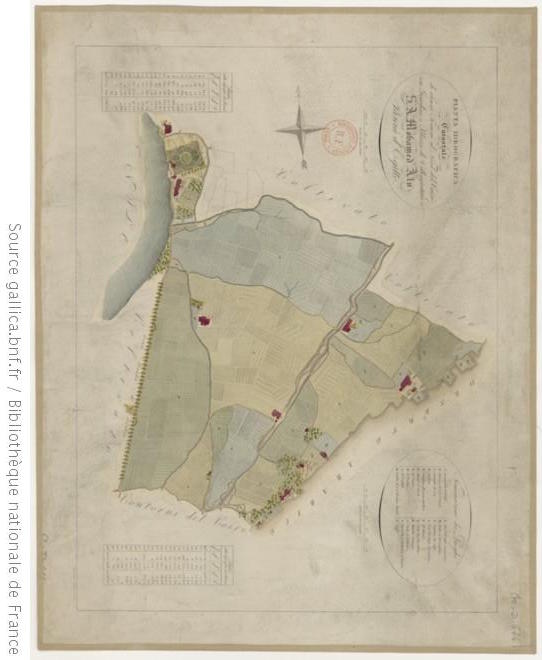

The different scenes of the film offer the initial state of Choubrah: a small village overlooking the River Nile located at the Delta countryside (Fig. 3). In fact, the etymology of the word Choubrah already tells the story of the site before its urbanization. Choubrah in Arabic Jobr’a has the Coptic root Schobro which means village, farm or manor. It takes this name from the fertile fields bordering the Nile on which the district was built.

Fig. 3

Abou Galil mentioned that Farouk Abdel Kader’s uncle, who died in 1945, was the last mayor of Minet el Sirg village. According to Farouk Abdel Kader’ descriptions: Minet el Sirg was a village that enjoyed all the features and characteristics of rural life: it is surrounded by agriculture lands, has a mayor Omda, a village council Dawar with a telephone, a chief of police Cheik khafar, and markets. Moreover, Choubrah was famous for its small water canals that derived from a main canal and flowed into the Al Boulâkîa canal that was built by Mohamed Ali to irrigate the fertile fields (Raymond, 1993). The agricultural lands of Choubrah were long famous for the planting of flowers and vegetables.

Farouk Abdel Kader emphasizes the role that the water canals has played as blue linear network structuring the ambiance of the district. He notes that there was a large canal that crosses Al Ter3a Boulâkîa at Victoria Square1. At this square, Chourbah’s canal was divided into two parts: one, today, is Abdel Hameed el Deep Avenue and the other is Ahmed Helmy street, named after the well-known journalist. In think this is why in the film the director has chosen to shoot a water canal as a part of the ambiance of Chourbah at that time.

Although urban sprawl encroached upon Choubrah during the second half of the 20th century, it retains some spatial traces of village footprints (Fig. 4). An example is the village of Minet al-Serg with its tiny streets, which today constitute the most ancient and narrowest streets in Choubrah (Abou Galil, 2007). On a recent aerial photo of the district, we can easily distinguish the former alignment of the streets corresponding to the ancient pattern of the village with Dayer el nahya – the ring road which delimits the village and separates the built space from the surrounding agricultural lands. It still carries the same name today.

Fig. 4

A palace

A charity event taking place at Choubrah Palace. A man, Mahgoub, who looks poor, walks into the palace after spending all he had to buy the cheapest ticket in order to participate in this event. He made this sacrifice looking forward to meeting Madame Ikram Nayrouz who may help him in finding work. He walked in hesitantly, feeling the difference between this world and his world of misery, poverty and sadness.

The dazzling light emanating from gigantic chandeliers draws his eyes to the roof. He watches carefully the fine drawings on the ceiling. He whispers to himself: “The price of a single chandelier would allow me to live like a prince.”

He looks at the big hall full of people and movement: a cosmopolitan society composed of elites – European, Turkish and rich Egyptians, very well-dressed as in the West, the men in their suits and the women in their evening gowns.

He walks to his chair and looks at the tables covered with dishes and bottles of champagne. Behind the classical music he perceives the footsteps of women whose heels echo on the marble floor. He sees the waiters in their identical costumes. He watches the Nymphaeum: a central lake with a platform in the middle of it where the orchestra sits. He continues whispering to himself: “Where am I in this life of beauty, luxury and wealth?”

A sound of clapping gets him out of his thoughts; he turns his head and notices an agitated movement towards the door. He sees a lady, the hostess of the party, in her embroidered gow and wearing a necklace and crown. As she walks, the men compete to kiss her hand, while the waiters bend over as she walks past them.

After the speech, the ball starts. The dance floor in the Nymphaeum is animated with the dancers who create a joyful scene and a cheerful ambiance.

Cairo 30 (Al-Qahîra 30), Salah Abou Seif (1966)

The film Cairo 30 is borrowed from a novel of the same name written by – Naguib Mahfouz, the Egyptian writer known as the Zola of the Nile. As its name suggests, the film features Cairo in the 1930s during a period of political turmoil. The novel tackles the huge gap between the rich and the poor and, more precisely, between the oriental, poor and popular Cairo and occidental, rich and aristocratic one; a gap that dominated the lived experience of the city at that time. In the film, Salah Abou Seif -the director of the film- has chosen Choubrah Palace to show the atmosphere of festivals that took place in the palaces (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5

The above-mentioned scene of the film reveals another temporality of the district: the royal and luxurious character which harkens back to the beginning of nineteenth century. This is the moment when Mohamed Ali Pacha – the governor of Egypt at that time – had decided to build, far from the city, an isolated palace. He has chosen a place near the village of Choubrah to be the site of his palace; this is why this residence is named “the palace of Choubrah”. In the following years, Mohamed Ali encouraged the elites, especially those coming from the royal family, to build palaces in Choubrah. This gave the territory the image of a luxury suburb during the 19th century; an image that lasted a long time, till a new transformation took place.

In Baedeker’s Plan 1885 (Fig.06), we see numerous palaces constructed in Choubrah. We would note Al Nouzha Palace, Tousson Palace – Tousson is Mohamed Ali’s eldest son- and Cicolani Palace. These palaces coexisted with the villages and the agricultural lands that were already present on the site. This proximity creates a contradictory atmosphere between the rich and luxurious aspect of the palaces on the one hand, and the poverty and informality dominating the scattered village, on the other hand.

Fig. 6

It is worth mentioning that, at the beginning of the 19th century, Choubrah played an important role in the urban and sensory history of the city of Cairo – that of a shift towards Western ambiance. In the interests of modernization and for the first time in the history of the city, Cairo had suffered from a crack destroying its urban unity. The city, which had always been dominated by a unique oriental ambience where the rich and the poor lived together, took on a double face through the urban interventions of Mohamed Ali. This fissure was reinforced by the successors of Mohamed Ali – notably the Khedive Ismail- who built a new Cairo: the Khedivial Cairo. As a result, the city entered into a long journey of social segregation that has continued to mark the city till now.

Sycamore trees

A poor young women, living in the Seida Zeinb district – a popular district at the heart of Cairo – falls in love with a rich solder. He comes with his car and picks her up, taking her to a calm place in order to enjoy a safe, car-free walk, in an ambiance that allows him to talk. He chooses the avenue of Chourbah. The camera captures the gigantic sycamore trees bordering the two sides of the avenue. Laila, his beloved starts to sing, the car moves forward and we see, in the background, peasant women walking along the avenue.

Laila, Daughter of the Poor (Laila Bent Al-Foukara), Anwar Wagdi (1945).

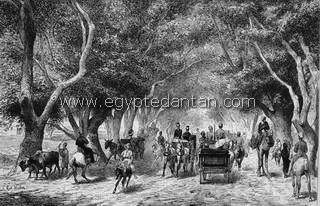

This very short scene, lasting for only few minutes, takes place in the avenue of Choubrah, where the young man has decided to take his lover (Fig. 07). However, these few minutes do not capture the deep urban memory that the avenue of Choubrah carries and the major role it played in modernizing the urban life of the city during the nineteenth century and beginning of the twentieth century. Initially, the avenue of Choubrah was constructed in order to connect Mohamed Ali’s Palace to the city. In 1847, one year before the end of his reign, Muḥammad ʿAli ordered “the construction of a wide road between Cairo and Choubrah. His vision for this street was to create an area for recreation and relaxation and should be wider and straighter than any other road in Cairo at that time. The linear form was created by a double row of sycamore and giant acacia trees whose branches meet in the sky and cover the alley with clustered green shadows. There were instructions to sprinkle it with water twice a day morning and evening to refresh the air in the summer and to settle the dust in the winter. Workers were appointed to maintain the cleanliness of the street and to tend to the trees (Raymond et al, 2001).

Fig. 7

It enjoyed a significant ambiance that marked many European travelers and urged them to document their experience of the avenue. Among them was Gérard de Nerval, the French poet and traveller who described it as “undoubtedly the most beautiful street in the world.” (De Nerval, 1867). Appearing in the travel diaries as avenue, boulevard or alley, the avenue of Choubrah was used as a linear promenade. The resulting green vault, impenetrable to the rays of the sun, was a singular urban feature and was associated with a unique experience: a refreshing and relaxing ambiance protecting the body from the sun, the eyes from the glare; a significant olfactory atmosphere produced by the mass of greenery (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8

“The Choubrah alley is also very beautiful in itself; there may not none comparable. It is bordered on both sides by gigantic sycamores which are about forty years old and which in our climate would not reach these proportions in less than two or three centuries … From a distance it looks like a series of colossal columns, violently twisted in all directions, upon which rests a powerful dark green vault …” (Charmes, 1880).

Moreover, in a certain number of travels diaries, travelers relate the experiences they had in the avenue of Choubrah to other urban experiences in different cities around the world. These testimonies class Cairo among the modern cities.

“Cairo as Paris has its own favorite promenade: Choubrah and its chic days. Choubrah represents le prater, le Prado, les Champs-Elysées of Cairo” (Joûbert, 1895).

This phenomenon of green-shadows favored the act of walking or strolling along the boulevard especially at the late afternoons al-A’ssari starting from 4:00 p.m. where a gentle breeze exists, especially in Choubrah, which is next to the Nile. During the weekend days, Choubrah alley received more people who used to take the holidays to get some fresh air. It was also the place where lovers met.

Unfortunately, this remarkable sensory experience didn’t last for a long time because in 1869 – the year of the opening of the Suez Canal – the Khedive Ismaïl gave orders to remove the sycamores and to plant them in the street that led to the Palace of the Island -known today as the Marriot Hotel- and on the boulevard Al-Ahram that leads to the pyramids, according to the descriptions of Ali Pasha Mubarak in his plans, Al Täwfîkîyä, written in 1887-1888. He explains that at the time of the sycamore trees remained only in the northern part of the boulevard of Choubrah. Indeed, this part is where the scene we have just presented was filmed.

A Cosmopolitan District

Cairo, Autumn 1933. A baby girl lies in her cot. She is screaming with pain, her eyes are blinded with a white ribbon. Her mother sets beside her and tries to calm her down. She continues crying until her father plays the violin. She stops and calms down as if she listens.

Cairo, Spring 1940. A two-story building with a staircase leading down a courtyard. On the façade we see a statue and a painting of the Virgin Mary… A bell rings and the silent scene becomes animated by young girls screaming and running down the stairs to reach the courtyard. We are in a catholic school in Cairo and the sound of bell indicates the break time. The camera shows a young girl wearing heavy glasses; some students start laughing at her. In no time, the situation gets out of control and they start to hit her. She falls down and loses her glasses. A teacher, dressed like a nun, intervenes; she punishes the girls, picks up her glasses, accompanies her to a room and talks to her to calm her down.

A few minutes later, the camera shots the young girl on her way back home. We are in a typical Egyptian street in popular district: we see an animated ambiance with street vendors occupying both sides of the street, children playing in the middle of the street, people negotiating prices, a donkey drawn carriage, we hear the hubbub of the market, the bleat of a sheep, the bells of a church. The camera follows the young girl between the traversing bodies and among them we see two soeurs in their gray suits and white veils, men in jilbab or suits and women in long dresses.

Lost in her thoughts while traversing the street, at the moment in which a military vehicle passes through the street, she feels a hand on her shoulder stopping her and a man’s voice tells her to wait. She looks at him with her broken glasses. He continues: go ahead, you can cross now. She crosses and stops in front of a door, the camera focuses on a metallic board on which is written: P. Gigliotti, Maestro di violino.

The film continues and the young girl grows up and travels to Paris and becomes a famous singer: Dalida, an Egyptian-French signer born in Choubrah from Italian parents; her father was the Maestro of violin.

Dalida, Lisa Azuelos (2017).

After the modernization of Choubrah in the beginning of nineteenth century, Mohamed Ali and his successors encouraged the installation of European communities in the district. After the construction of a New Cairo by Khedive Ismail in the middle of nineteenth century and Helopolis in the beginning of twentieth century, Choubrah witnessed an internal immigration of the rich to the new cities (Fig. 9). Choubrah was afterwards inhabited by poor Europeans. In fact, the district was a favorite destination for the European community who migrated from east and middle Europe to Cairo in order to find work. This was no wonder, at that time, and thanks to vast urban project developed during the reign of Mohamed Ali, Egypt was the destination for those in Europe seeking work, and coming mainly from Italy, Greece and Cyprus (Abou Galil, 2007). It was also the site where the Syrian and Lebanon communities who worked in commerce, craftsmanship and in catholic missionaries had chosen to live in Cairo. They started to settle in the southern part of the district, close to the city. Urbanization increased thanks to the introduction of the tramway. Foreigners (Khawāgāt in the colloquial Egyptian language) lived side by side in the same place with the locals. These different communities had built schools, hospitals, and clubs, such as the Italian ‘Salesian’ school and the Greek club (which became known as ‘Isco Club’).

At that time, Choubrah was a true cosmopolitan district. The historian Mohamed Afifi (2011) shows how the district was alive with several languages including Italian, Greek and Egyptian, with no hostility between the inhabitants who constituted the Egyptian nationality at that time. That is exactly what the film Dalida shows: the co-existence of these communities adds touches to the daily sensory experience of the district: at the level of sound, we hear different languages, the bells of the church, we see the uniform of the students in schools, who mix together in a popular Egyptian context in which street vendors occupy the street, in which children and animals are present, etc (Fig. 10).

Fig. 10

The novel A Girl from Choubrah (Ghanem, 2005) tackles the same issue: how the European communities lived in Choubrah during World War II (Ghanem, 2005). This is the story of an Italian lady called ‘Maria Sandro’ one of Choubrah’s most beautiful daughters in the thirties. The novel shows her daily life during the mid-20th century. She was the daughter of an Italian mother and father who used to go to church on Sunday mornings with her Greek neighbor. Christians who inhabited the area at the time continued to occupy it, and Europeans married Egyptians. This cosmopolitan spirit was also the subject of the novel Choubrah Naʿaīm Ṣabry (2000) which was about the interwoven lives of Muslim, Christian and Jewish families with Greek, Armenian, Lebanese, and Palestinian extraction in the mid-twentieth century.

An Avenue

The camera moves slowly to give a panoramic view from the ceiling of a residential tower. A very dense urban fabric appears and a very long avenue reaches the horizon while dividing the urban fabric into two parts. We see buildings from different eras with different heights and different colors and finishing materials. We see a line of trees bordering the avenue.

A travelling shot follows the avenue, capturing buildings with an informal distribution of advertisement along the facades, while on the ground floor we see different types of shops with different size and colors. People are strolling along the avenue together with the cars. The Camera scans canyon streets with trees aligned on both sides and their branches meet, providing an important presence of greenery in these streets.

Choubrah Roundabout (Dawärän Choubrah) , Khaled Al Haggar (2011).

Lola and Om sami are neighbors of the same landing in an ancient building in Choubrah near Dawärän Choubrah. They belong to different religious sects: Om Sami is Muslim and Lola is Christian. The series is named after a main space along boulevard Choubrah where it intersects with boulevard Kholosi “Dawärän Choubrah”. Om Samy, a mother of three children and a grandmother of two, lived her life in the district after her marriage. Due to a financial difficulty and the high price of the apartment, her children want to sell it. So begins a struggle due to her attachment to the place and to her social context, with its neighbors, merchant, street vendors, housekeeper, etc. (Fig. 11).

Fig. 11

The TV series focuses on her sense of attachment, and the camera traverses different places in the district to show its way of life: the boulevard of Choubrah, the residential canyon streets, the popular cafes, the markets, street vendors, and, in particular, her Christian neighbour Lola.

In fact, the presence of Christian Copts is central in the social composition of Choubrah. This aspect is represented in cinema as a way of showing how the two religious sects live together in harmony: in the ringing bells of the church, the catholic schools, the Christian ceremonies, the bodily presence of the Christian who, through certain clothes and symbols define the atmosphere of the district, all mix with the call for prayers, and the veiled women. Choubrah represents the unification “between the cross and the crescent” which remains the memory of the union and of the acceptance of others.

This actual state of informality and popularity gained force after the revolution of July 23, 1952, after which Egypt changed its political regime form royalty to republic. In that time, Gamal Abdel Nasser with his socialist background initiated an urban policy aimed at making Cairo accessible to everyone, especially the poor. A massive immigration from the nearby villages in the Delta to Cairo took place (Fig. 12). Choubrah was affected due to its location on the northern periphery of the city in its intersection with the agricultural land of the Delta. Many informal settlements appeared, such as al-Kasyrain, al-Khamassya, al-Zawya al-Hamra’a, hamlets attached to Choubrah, and which extended to al-Mezalat (Abou Galil, 2007, p. 437).

Farouk Abdelkader tells the story from his lived experience: “Choubrah is the first station for those coming from the Delta to Cairo.The district had a Delta bus station that was metaphorically called “Al-Monoufia Airport”. It took this name due to the huge number of immigrants coming from the al-Mounofia governorate who settled in Choubrah. He describe the scene in a mocking bitterness: “When we were young, we used to say that the Monoufien’s mother gave birth on the highway leading to Choubrah. She shows the child the direction and leaves the newborn alone to arrive as if by accident in Choubrah to begin his journey. Then he adds: “The Monoufian then comes to Choubrah and holds in his hand a piece of paper on which is written an address of someone of his family. As soon as he arrives, his family helps him find a small job and a house. This is what helps people to settle in Choubrah forever. And 95% of the inhabitants – just behind the al-Khazendarah mosque after Däwäran Choubrah – are from the Delta; among them is Ghali Choukri who works in the Arab literary criticism ” (Farouk Abdel al-Kader, in an interview with Hamdi Abou Galil, 2007. p. 439). (Abu Galil, 2007, p. 438).

The urban history reveals another aspect of the singular composition of the district. During this time, the district underwent two major urban transformations. The first was the gradual invasion of the territory by an “informal” dynamic, in order to ensure a social habitat for the middle class and especially the working class (Haeringer, 2002). In this informality the small irrigation canals were filled and became the main road fabric of the district, while the urban lots followed the former agricultural land division.

The second aspect was the nationalization of the palaces and villas in the district following decisions taken after the 1952 revolution which made them become public schools or institutions. We can point to the al-Nouzha palace which became the al-Tawfikya high school, and the Tousson palace which is now Choubrah Secondary School. Ciccolani Palace has become the School of Independence. Unfortunately, in their current state these buildings are deteriorated and others have destroyed, such as the palace al-Nouzha which is often mentioned in several travel journals in Choubrah during the 19th century.

Choubrah: A Story of a Rural-Urban Struggle

Despite the fact that the selected films tackle Choubrah at a specific time in its history – during 1930s &1940s – they show completely different facets of the district. The huge difference between the scenes makes it hard to believe that they share the same territory. We are plunged into different ambiances: those of the village, of palaces, of popular streets. Each scene sends us back to a different temporality of the construction of the site, unveils a specific superposition of experiences and reveals the layering of states (rural, urban…) by which is prepared the becoming of a unitary and homogenous popular ambiance.

Reviewing these films together tells another story: a struggle of ambiances between rural and urban features. In fact, the popular origin of Choubrah comes from the villages that, with a sudden transformation in the beginning of nineteenth century, had to cohabit the territory with a luxurious urbanity. The poor and informal ambiance of the village lives side by side with the rich, aristocratic one of palaces, as two separated worlds that sometimes meet in the boulevard of Choubrah. A century later, at the beginning of the twentieth century, with the introduction of the tramway on the one hand and the construction of the modern city center of Cairo by Khedive Ismail on the other, the urban encroachment reached the southern part of Choubrah and the district welcomed another social class of well-educated and cosmopolitan societies. The gap between the two ambiances grew narrower.

Until the 1930s and 40s, these societies didn’t really mix, as each group belonged to a specific social class and appropriated a delimited territory in the district: the southern part of Choubrah was an urban district occupied by Egyptians and Europeans, the northern part was dedicated to palaces and country houses that stand side by side with the poor villages. In 1952, the informal character gained power with the massive arrival of villagers to the district, which reinforced its popular character on both social and urban levels. This compositional process produced a singular form of urbanization that lies on the threshold between rural and urban fabrics. This spatial and social background offered a place in which a specific urbanity could merge: a rural urbanism urbanité villagoise.

The study of the cinema through the prism of the ambiance-palimpsest points out the capacity of cinematographic scenes to represent the ambiance of the city as a process, as an evolving organism that incessantly changes.

If cinematic scenes are snapshots recording the ambiance of the city within a specific spatial and temporal frame, , this article underscores a new potential for this important corpus. By means of the collage, selection, and recomposition of the different cinematic scenes, the cinema participates in an analysis of the city on the diachronic scale and develops a retrospective look upon the city of Cairo.It participates in an in-depth rereading of the city .

The chosen scenes help in understanding the process that gives rise to the cultural diversity that cohabits and coevolves within a single urban context. Indeed, the evolutionary look that the study of cinema provides decodes the composition of a Choubrahian character that was consolidated, gradually, from the elites of the royal family subsequently becoming cosmopolitan (Egyptians and Europeans), to the arrival today, at a cohabitation of Christians and Muslims constituting a veritable palimpsest of ambiances.

Noha Gamal Said

References

Bînt men Choubrah, A Daughter of Choubrah (trad.) (2004), Abdel Hamid, Gamal.

Cairo 30 (1966), Abou Seif, Salah.

Dawärän Choubrah, Choubrah Roundabout (trad.) (2011), Al Haggar, Khaled.

Dalida (2017), Azuelos, Lisa.

De Nerval, Gérard. (1867). Voyage en Orient. Nerval 1851. Michel Lévy Frères. Libraires Editeurs. Paris.

Laila Bent Al-Reif, Laila, the Girl from the Country (trad.). (1941), Mizrahi, Togo.

Laila Bent Al-Foukara, Laila, Daughter of the Poor (trad.) (1945), Wagdi, Anwar.

Charmes, Gabriel (1880). Cinq mois au Caire et dans la basse Egypte. Charpentier.

Afifi, Mohamed (2011). Mohamed Afifi rediscovers the tramway of Choubrah. Al-Ahram Journal. 9 septembre 2011.

Gamal Said, Noha (2012). Choubrah entre le passé et le présent : le palimpseste des ambiances d’un quartier populaire au Caire. In : Thibaud, Jean-Paul ; Siret, Daniel, Ambiances in action – Ambiances en actes. Actes du 2nd congrès international ambiances, Montréal. 19 – 22 septembre 2012. Grenoble : Réseau international Ambiances : École nationale supérieure d’architecture de Grenoble. p. 493-498.

Gamal Said, Noha (2014), Vers une écologie sensible des rues du Caire : le palimpseste des ambiances d’une ville une transition, Thèse de doctorat, Grenoble : Université Grenoble Alpes.

Ghanem, Fathy (1986), Bînt men Choubrah, A Daughter of Choubrah (trad.). Cairo, Dar Elhelal.

Haeringer, Philippe (2002), Le Caire et la refondation mégapolitaine au Proche-Orient: une comparaison avec Istanbul et Téhéran. In : EurOrient. n° 12. L’Egypte. Ellipses. p. 57-104.

Joûbert, Joseph (1895), En Dahabieh: du Caire aux Cataractes. E-Dentu, Paris.

Kracauer, Siegfried (2010), pour l’édition française. Théorie du film, la rédemption de la réalité matérielle, Paris, Flammarion.

Raymond, André (1993), Le Caire. Paris : A. Fayard.

Ṣabry, Naʿaīm (2000). Choubrah. Dar Al Shourouk, Cairo.

Tadamun, 2016. Shubrä. Url : http://www.tadamun.co/?post_type=city&p=8352&lang=en&lang=en#.YEHV5h1CfVq.

Thibaud, Jean-Paul. (ed.). 2007. Variations d’ambiances: processus et modalités d’émergence des ambiances urbaines. Grenoble : Cresson, Rapport de recherche. n°67. 310 pages.

1 Named after a visit of Queen Victoria, the queen of England who visited Egypt and Choubrah in order to visit the European community living there.