It’s more than sixty years since Pickpocket (1959) was made. Can there be possibly be anything more to say? Probably not. However, here are a few brief thoughts after having seen it again recently…

***

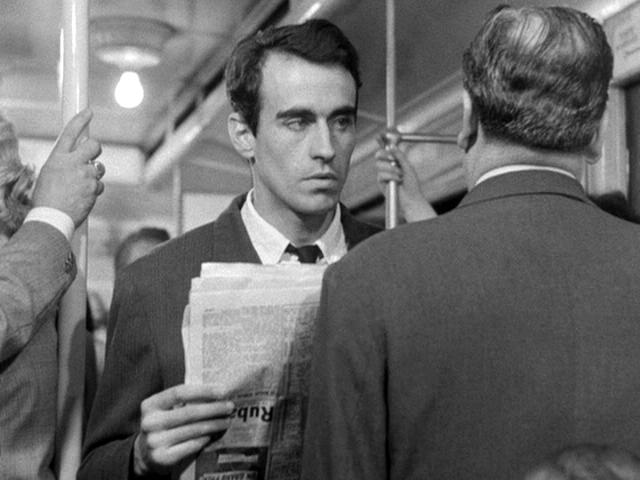

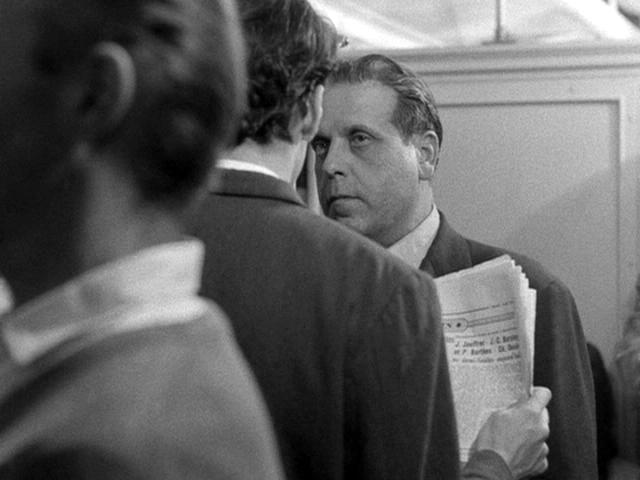

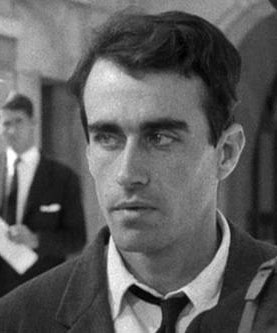

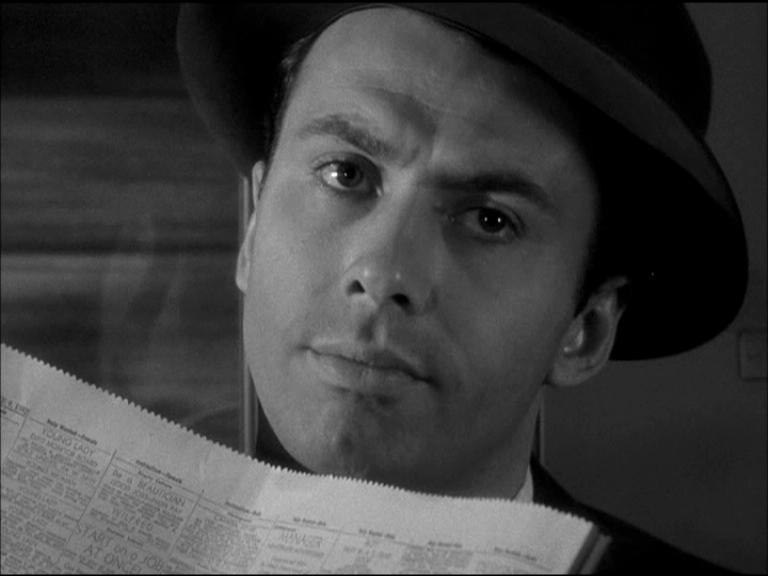

The sexuality of the activity of pickpocketing itself and especially of the orgy at the Gare de Lyon has been hinted at elsewhere, but only hinted at and ever so gingerly, at that. The looks that are exchanged between Michel (Martin LaSalle) and his victims or intended victims are not innocent looks. Theirs are not the casual meeting of the eyes of two strangers, a glance that lasts a nanosecond before each one pulls away in embarrassment, disinterest or indifference. More is going on in that brief interchange than the mere act of looking. What is Michel looking for, except not to have his look returned? Or does he want it returned? What do the potential marks see when they see Michel looking at them so frankly, so boldly, so unashamedly, when Michel brings his body as close as possible to his intended victim— someone who is invading their space? someone who intends to harm them? a sexual aggressor? This is a naked glance that reveals more than is intended or maybe exactly what is intended. When the victim will recall the scene, he or she will remember it as a furtive kind of rape—without the sex. If Samuel Fuller can call the kiss of a pervert The Naked Kiss (although one would like more specifics to know exactly what makes it so different from an ordinary kiss, so that all of us can stop wondering if we’ve ever received one, or, worse yet, given one), the glances exchanged by Michel with his intended victims might very well be called The Naked Look.

The Naked Look

the racetrack

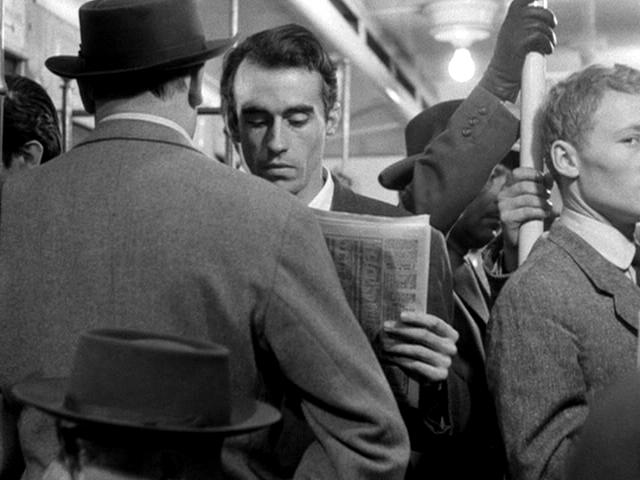

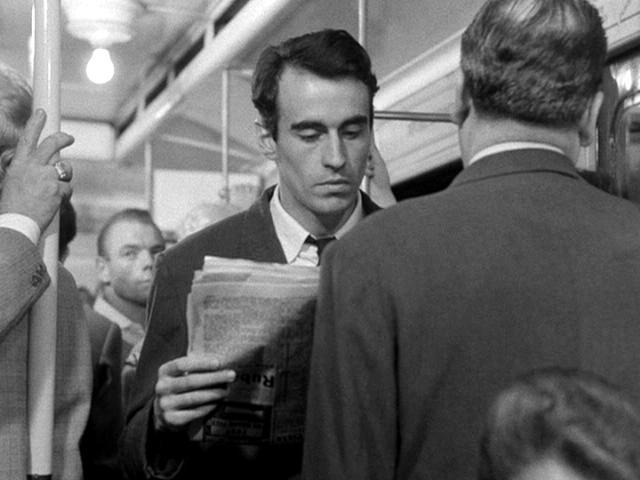

the métro

the railway station

the racetrak

The Naked Look—Details

To ignore the sexual aspect of these looks is, it seems to me, to willfully ignore what is happening on the screen. Certainly the breathtaking ballet of stealthy fingers and hands dipping into private unseen pockets and closed pocketbooks is a sexual act as thrilling, at least for Michel and his partners, as the money—which Michel, other than as a symbol of his triumphs, has little or no interest in. The only look I can compare Michel’s to is that of the main character in Tomás Gutiérrez Alea’s Memories of Underdevelopment, as he hungrily prowls the street looking for women. An unintended parody of that look is that of the hospitalized, vampire-like nymphomaniac in Antonioni’s La Notte. (And, just for curiosity, do Italians institutionalize “nymphomaniacs,” and in the cancer ward, of all places?)Michel may not be a sexual predator per se, but the intensity of his gaze is as much a violation of the person he is looking at as if he is imagining them without clothes on—in contrast to his response to Jeanne (Marika Green), whom he barely glances at, despite her extraordinary beauty. Compare Michel and his intended victims to Fuller’s Pickup on South Street, as Richard Widmark looks blankly at Richard Kiley, as if he is performing a business operation while lifting the gun (!) out of Kiley’s inside pocket. Kiley, meanwhile, looks around goofily, studiously feigning nonchalance, seemingly oblivious to Widmark’s closeness—or indeed the warmth of Widmark’s breath on his face. Clearly, the decision, for whatever reason, to make picking pockets a sexual act is Bresson’s, and not necessarily the nature of the activity.

***

And, talking about the sexuality of Pickpocket, Michel’s, for want of a better word, relationship with Kassagi, the expert pickpocket who becomes for a while his mentor and then his cohort, in fact begins like a homosexual pickup. Kassagi waits outside Michel’s house, waiting for him to come out, and silently accompanies Michel without even addressing him, as if it is understood why he has come for Michel. It is not unlike the heterosexual version, without the romanticism, of a similar scene in Bresson’s Les Dames du Bois de Boulogne, in which Paul waits in front of Agnès’ building to catch a glimpse of her and seize the opportunity to approach her.

***

In the train scene, shortly after Kassagi and Pierre Etaix have scored a hit, to make room in the narrow passageway, the two of them, with no space between them, both facing the aisle, back up together into the train compartment. Even though they are stony-faced and expressionless, by their actions, they are miming nothing so much as sodomy. To put it in the rudest possible terms, it’s almost as if they are stealthily slipping into the compartment to partake in a quickie.

***

In Pickpocket, the austerity of Diary of a Country Priest and A Man Escaped is far behind us and we are back in the land of the lushness of Les Dames du Bois de Boulogne, although considerably understated here. Pickpocket has dozens of tracking shots, more than in any other Bresson film. The camera follows Michel and catches up with him. Or dollies into him while he is facing the camera or pulls away from him as he walks towards the camera. At the very beginning, in the first racetrack scene, the stationary camera waits for Michel to enter the frame and starts following him as he walks up to the woman in the wide-brimmed straw hat. To accommodate what will be a close-up, the camera booms up while it is tracking. Michel stops, the camera stops, the woman turns around and looks directly at him. Seeing this film again recently, the camera movement surprised me, first of all, because it looks so much like a real movie, using the grammar of a real movie—actor enters frame, camera starts moving, camera booms up while moving, actor stops (we can even see Michel looking down at his marks checking for his final position), camera stops, actress turns around—rather than a Bresson film. It surprised me also because I remembered the film as having a very naturalistic look, as if the film frame appeared not have been manipulated. How wrong I was. When I re-saw, also relatively recently, The Bicycle Thief, I was equally surprised at the number of complicated tracking shots in this seemingly simple and realistic film. As some but maybe not all viewers know, a dolly shot is much more complicated to execute than a stationary shot or a panning shot. It has to be rehearsed many times over. There are usually two men pushing or pulling the dolly and it has to start at a certain place and a certain moment and has to end in a very specific place. In those days, more often than not, tracks had to be laid down to facilitate the camera’s movement, although not on very smooth surfaces, such as the bank scene in Pickpocket—making the operation even more complicated. It is extremely difficult to do in any case but much more so when working with non-professional actors, because the non-actors have to duplicate their movements with precision over and over again, walking neither too fast for the camera, thereby getting out of camera range, or too slowly, so that the camera overtakes them. When I noticed the tracking shots in The Bicycle Thief—the only other time I had seen it was when I was a teenager, long before I paid attention to such things—it completely destroyed the fiction that we are seeing something real that is unfolding in front of us. I was no longer in a drama that is spontaneously happening, albeit with the camera present as an unobserved witness. We are obviously watching a very highly controlled and contrived event in which there is clearly a camera present, not only recording but also dictating as well as knowing in advance which way, when and where the actors will move to. When we watch Visconti’s La Terra Trema, the complicated tracking shots do not seem to get in the way of the film because either we are already aware that Visconti is an opera director as well as an operatic director, or the very carefully studied pictorialism from the very outset of the film indeed suggests a much more consciously designed canvas. Visconti is as aware as we are that the non-professional actors, the Sicilian dialect and the real locations are just handmaidens to the expansive epic he is creating, only one part of his objective. Mixing up the reality of the situation with the artifice of his very concise framing and lavish camera moves has always been part of his strategy, even is his so-called “neo-realist” films.

***

Although, at the time when they were first shown, one probably would not have made a connection between films as disparate and unique as Pickpocket (1959), Kubrick’s The Killing (1958) and Hitchcock’s The Wrong Man (1957), it seems to me that they have a great deal in common. Well, yes, they’re all in black and white and in all three of them the racetrack is an important ingredient. (Henry Fonda, in The Wrong Man, likes to play the ponies. That’s even given, by the police, as his motivation for committing the robberies). To varying degrees, they all have elements of unsentimental, documentary-style naturalism, although the low-angle lateral-tracking shots, from room-to-room, à la Ophuls, in two of the apartments in The Killing might seem to disqualify it, and all three of them, in great naturalistic detail, are how-to films—how to be a pickpocket, how to commit a heist, and how to get arrested—the step-by-step process of being questioned, booked, imprisoned, and indicted by the police.

But there’s more than these surface similarities that join these films to each other. They all, in their own relentless, almost airless way, provoke a dream-like ambience in which everything seems to happen in slow motion and the viewer is as powerless as the characters are to interrupt that dream. Each of the films has scenes repeated over and over to the extent that we’re not quite sure where we are on the mobius strip. Pickpocket, for instance has fourmétro scenes, four railway station scenes and is book-ended by racetrack scenes. The Killing starts with the horses coming to the gate in the main title sequence. In reconstructing the chronology, as we get closer and closer in time to the robbery while the narrative tracks various characters at the time of the race, these shots are repeated again and again, as are shots of the public address system, announcing the race. The cubistic structure zigzags back and forth in time, stretching as well as compressing time, creating a maze from which it’s impossible for the viewer to extricate himself. The sense of being trapped in someone else’s bad dream is re-enforced by the repetition of the brawl in the enormous betting lobby at the racetrack when it is incorporated in different versions in different flashbacks. The identical lateral tracking shots in this concrete-walled, ominous space that is worthy of Fritz Lang in his UFA days seem like they’re happening in slow motion. In The Wrong Man everything happens at least two times as well. As in The Killing, it starts with a scene that will be repeated several times throughout the film—the Stork Club, where Emmanuel Balestrero (Henry Fonda) is a musician. A long shot of the club, with the balloon-filled dance floor is used under the main titles and is repeated several times in the course of the film, always accompanied by generic lounge music, an uncharacteristic Bernard Herrmann tune, giving the sense that the same exact music is played night after night in this pleasure palace. In may be fun for the patrons but not for the people who work there and it gives a very clear indication of how trapped Balestrero is in every area of his life, including this one. The repetition of line-up scenes, incarceration scenes, Fonda forced to parade up and down in local stores for identification purposes, Fonda being moved from one prison to another, scenes with the lawyer—all like the repetitions in The Killing and Pickpocket, g ive a sense of a world from which there is no exit, no escape.

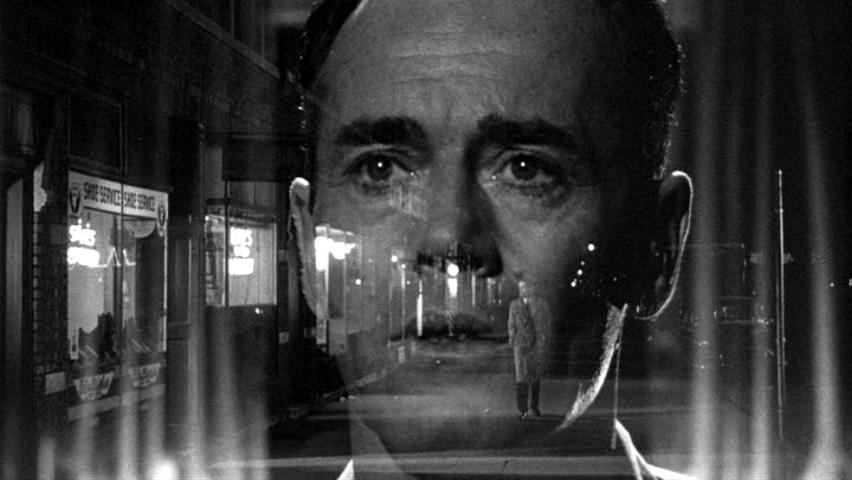

And the ultimate dream-nightmare effect is the close-up of Fonda, after a mistrial has been declared and they have to start a new trial all over again, for a crime he didn’t commit. The nightmare continues. It clearly will for the rest of his life. He starts to pray. There is a superimposition, on his face, of the dark street with the stranger, the right man, walking very slowly—it’s a 25-second shot—from the end of the street till his face, too, becomes a close-up, merging with Fonda’s.

***

To be more precise about how Pickpocket at times gives the impression that it is like a dream, filmed underwater: if one examines the backgrounds very carefully one will notice the same extras reappear in the métro sequences. The same is true of the railway station sequences. The dream-like, almost-surreal feeling is that one has seen these anonymous people before. And indeed one has, in the previous scene, and maybe even in the very same scene.

Métro A Métro B Métro C

The blond man in the sports jacket on the far right of the frame, looking at the camera, (métro A) is in the second of the four métro scenes. In the third métro scene, he is sitting in the incoming train (métro B), on the right hand side, but in the very same scene, he is also entering the métro, walking ahead of Michel (métro C).

We next see him at the railway station, two years later, wearing the same clothes, when Michel returns to Paris (railway A).

Railway A

Métro D

Métro E

In the same scene in which the young man appears (métro C) walking ahead of Michel, there is a woman walking behind Michel (métro D). She is also waiting to get onto the platform (métro E, right side of the frame) in the very same scene, as Michel exits.

Métro F

Railway B

The woman standing behind Michel, on the right (métro F), when Michel is confronted stealing is the same woman (railway B) ahead of Michel, on the left side of the frame, when he returns to Paris. In addition, the man to the left of Michel railway B is the same man who is behind him in métro F. A better view of him is in railway A, to the left of the young blond man.

One could go on, but the point is made. This has more to do with the exigencies of filmmaking than intention—you have only such-and-such a time available to you to shoot in the métro. You have to hire actors to be extras in the scene(s). Obviously, the fewer extras you hire, the less it will cost. You count on the assistant directors to position the background actors, as they are sometimes called, as skillfully as possible, so that there are no jarring repetitions. But still, they do occur. So, the budgetary restrictions unwittingly add to the dreamlike air of these sequences—an unpredictable and impossible to foresee by-product in the making of the film becomes the source of (only one) its many discomforting effects as a work of art, after the fact.

***

Two of the most thrilling scenes in Pickpocket are of Michel at the racetrack. In both of them he and the people in the frame with him are looking off- screen into the distance. We do not see what they are seeing. But we are watching them watching something else, which we, even though we know what it is, are not permitted to see. We look at all the faces besides Michel’s. They are immobile, like the people in Last Year in Marienbad, who are posed in mid-action, unable to move. We watch Michel, assuming we know what is on his mind. We also know that it is not the same thing that is going through the minds of his fellow horse-racing spectators. And we also know what is going through the mind of the detective who is planning to entrap Michel. But all of their faces reveal nothing, seem to react to nothing, in fact, see nothing. The spectacle that we are watching is that of the spectators watching another spectacle, which in most films would be the spectacle that the director would have us watch. Since we have no reason to be interested either in the races or their outcomes, we are diverted from the horse-racing spectacle to that of the deliberately inexpressive faces, each of which is masking differing emotional temperatures. We have to imagine the races, just as we have to imagine the spectators’ (different) emotions. Again, whether this was a financial decision or not, (to show the actual horse races)—and to some extent it probably was, results in a breathtaking coup de cinéma—a Day at the Races, make that two days, without a horse in sight. But even when we do finally get to see horses in action—in the jousting scene in Lancelot du Lac—we only see the bottom half of them, unable to identify the riders. Bresson can’t or won’t provide the spectacle because the spectacle, for Bresson, resides elsewhere. It’s an unseen interior spectacle, if such a thing is possible, that he’s interested in, not visible to the naked eye, and it is to that spectacle that Bresson directs our attention and forces us to refocus our expectations.

***

When Michel flees Paris, he walks out the front door and looks. He seems to be spotting a cab, but Martin LaSalle, not being a professional actor, at least at the time, is unable to mime his eye movements to suggest following a cab. (This is before La Salle studied at the Actor’s Studio.) Clearly, a real car was not provided, at the shoot, to permit him to perform this action realistically. He is also unable to mime, “hailing a cab”—raising his hand too late and too timidly for the cab, if there were a cab, to actually see him. Also, he is too close to the building for a cabdriver to have noticed him. We also see, in the very next shot, in which he steps into a cab, that there were cars in front of the doorway making it even more unlikely that the phantom driver would have spotted him. Again, his act of looking for where a cab might possibly be, combined with a shot of him stepping into a cab is supposed to convince us, as in the horse race, that we have seen what we actually do not see, just as, in Bergman’s Persona, in recollection, when we think of Bibi Andersson’s exceedingly graphic description of lovemaking on the beach, we actually think we saw what we most assuredly did not see. When Michel steps into the real cab that has miraculously appeared, probably shot at another time and another location, we or at least I am impressed by the Eisensteinian dialectic of editing that by its very juxtaposition suggests that something that could not have happened really is taking place. This is one of the few instances in which Bresson uses Eisenstein’s “vertical” editing techniques whereby one shot is placed after another to give the impression that the two are related, rather than Bresson’s usual lateral editing which implies temporal and spatial ellipses between shots.

***

Another example of Eisensteinian editing in Pickpocket: when Michel, at the racetrack the second time, picks the inside jacket pocket of the detective who was sent to set him up, it is almost painful to watch the position of Michel’s hand and arm, not in the same frame as his face. Physically, we are aware that he could not possibly perform this action, unless he was a double-jointed circus performer. Bresson well understands our discomfort, since he is the author of it. He makes us aware of the physical impossibility of the act by making each individual viewer almost wince as he tries, mentally, to emulate the physical action but finds himself unable to do so.

It’s not dissimilar to the discomfort one feels watching Hitchcock’s Strangers on a Train, when Robert Walker, trying to retrieve the lighter he dropped in a sewer, frantically thrusts his hand through the grillwork.

He is performing physically impossible feats as his hand reaches deeper and deeper into the sewer, until he is able, finally, to reach the lighter.We viewers feel the same anxiety and can even empathize with his pain as he performs this un-doable feat—because he knows and we know that what he is doing is virtually impossible to do.

He finally, and very unrealistically, retrieves the lighter and even though we know that he, Bruno (Robert Walker), needs the lighter to implicate Guy Haines (Farley Granger) in the murder that Bruno committed, the audience is relieved that he was able to get the lighter back.

Even though we and everyone in the film knows what a psychopath he is, Hitchcock, for one brief moment, makes us complicit in Bruno’s actions. We want him to retrieve the lighter, almost as much as we want him to fail in his plan.

***

Bresson’s theories of acting are too well known to rehash. He does not want actors, he does not look for actors. He studiously avoids actors, he says. But he does nevertheless look for something when he is looking for a person for a role. In an interview about Au Hasard Balthazar in “Cahiers du Cinema,” Godard, gently and without trying to provoke him, tries to get Bresson to concede that once you put a person in front of a camera, he or she is already an actor. What else could they possibly be by the time they are shooting take 23? I would add, what could they possibly be when they are already rehearsing a complicated tracking shot for the 10th time? Bresson remains adamant. His denials notwithstanding, of course he is looking for actors. He is looking for people who convey something rather than nothing. The completely empty face does not interest him. !f some spark isn’t ignited between a face and a camera, nothing will happen on the emulsion of the film and nothing will register on a screen. His direction of his performers, or modèles, as he chooses to call them, seems to have been an exquisite balancing act between humiliation and exaltation. That Bresson has chosen people who subsequently had some kind of career in films suggests either that Bresson is a very good talent scout or despite his, from all accounts, merciless browbeating, makes his actors fall in love with the art of acting. For all those who slipped back into the obscurity from which they were momentarily plucked, there seems to have been an equal number who, subsequent to their experiences with Bresson, sought careers in films. Dominique Sanda is perhaps Bresson’s most famous alumna. Nicole Maurey, Marika Green, Anne Wiazemsky, Isabelle Weingarten also went on to appear in other directors’ films. And what of Jean-Claude Guibert who plays Arnold in Au Hasard Balthazar and then comes back to play Arsène in Mouchette? Is he not already an actor by the time he has finished his role in Balthazar? Is it possible to retain your virgin status as a modèle forever, or is there no expiration date on it? Or how about Pierre Klossowski, not a professional actor but, by his commanding looks and presence, an actor nevertheless, even though his calling was elsewhere? And there’s Francois Leterrier, Claude Laydu, Pierre Etaix, Roland Monod, among others, to be accounted for.

***

Then there’s the nagging, probably unasked, definitely unanswered, at least for me, Dominique Zardi question. Zardi is an extra in one of the métro scenes. Even though Pickpocket was made in 1959, it was not released in theU.S. until 1969, by which time Zardi had been seen, by attentive filmgoers, in character roles in nearly a dozen French New Wave films, mostly by Claude Chabrol. Zardi, a veteran actor of over 300 films (!), including 30 by Chabrol and 40 by Jean-Pierre Mocky, is clearly identifiable for anyone seeing Pickpocket today, for the first time. He is no longer a neutral extra but an extra who jumps out of the background, announcing, not his anonymity, but his very distinctive individuality. How does that affect the perception of the film, the realization that he is not just another face in the crowd? Does his appearance as a modèle extra preclude the fact that he was an actor looking for work? Or is he a modèle who became a successful actor after his modèle apprenticeship? Or does his very appearance and subsequent career shatter the myth of the modèle? Of course, it doesn’t really matter one way or the other, but it does it does seem to muddy the zealously adhered-to distinction Bresson makes about legitimate, professional actors vis-à-vis what he calls his modèles.

***

Has anyone traced the trajectories and genealogies of the careers of Bresson’s “modèles” after they’ve become mere actors? Has anyone compiled a list of who has gone on to do what? Maybe there is some kind of elaborate pattern there. Can one discern a figure in the carpet? And what is one to make of this vulgar, earthy factoid—that two of Bresson’s most striking alumni, Marika Green from Pickpocket and François Letterier from A Man Escaped, have found their way into the Emmanuelle movies, Green as an actress and Letterier as a director? Coincidence? Chance? The vagaries of show business? Isabelle Weingarten (Four Night of a Dreamer) was offered a role in one of the three Emmanuelle films but turned it down.

Let’s add, parenthetically, that the actress Eva Green, star of Bertolucci’s The Dreamers, the TV miniseries Camelot, a Bond girl in Casino Royale, and more recently in the hit Netflix series Peaky Blinders is the niece of Marika Green and the daughter of Walter Green, the boy to whom Anne Wiazemsky is betrothed in Au Hasard Balthazar. She was also in a Roman Polanski film and several films by Tim Burton.

François Letterier’s son is Louis Leterrier, the director of The Clash of Titans, The Incredible Hulk, and most recently, two installments of The Fast and the Furious. The genealogical tree has many branches. The wind indeed does blow where it will…

***

“I sometimes read (I am thinking of the reviews after Le Samourai and L’Armée des Ombres came out, ‘Melville is being Bressonian.’ I’m sorry but it’s Bresson who has always been Melvilleian. Take a look at Les Anges du Pêché and Les Dames du Bois de Boulogne, and you will see that they aren’t yet Bressonian. Look at Le Journal d’un Curé de Campagne, on the other hand, and you will see that it’s Melville. Le Journal d’un Curé de Campagne is Le Silence de la Mer!….As a matter of fact Bresson did not deny it when André Bazin put it to him one day that he had been influenced by me.”

“Melville on Melville” by Rui Nogueira

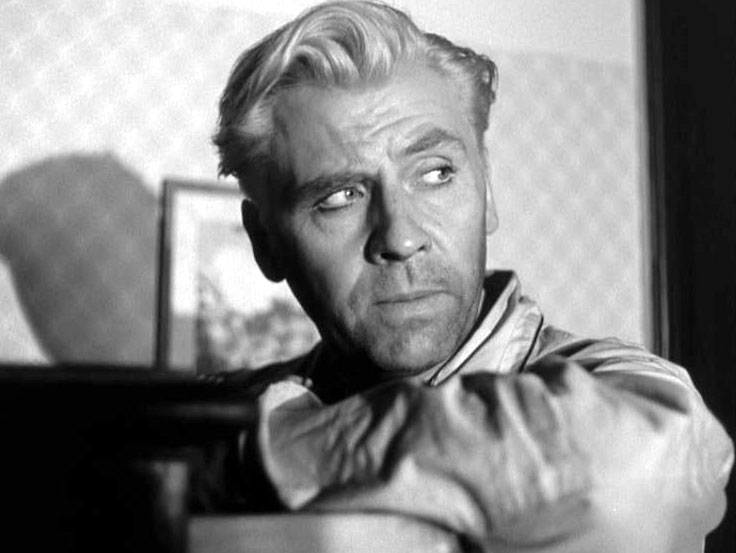

Perhaps, taking the métro scenes in Pickpocket as a challenge, or maybe just to show Bresson up, Melville invents the brilliant métro pursuit of Jeff Costello in Le Samouraï, besting Bresson at his own game. In Les Enfants Terribles, Melville also uses classical music in a way that will influence Bresson, several years later, in A Man Escaped and Pickpocket—sacred sounding music, if not actually sacred music itself, in a secular, contemporary situation. Perhaps Melville repays Bresson for that influence by using a theme from Les Dames du Bois de Boulogne in Le Doulos, not as an homage but tit for tat. But Melville will take his starkest revenge much earlier, when he makes Bob le Flambeur in 1955. Has no one noticed the resemblance between Bresson and Roger du Chesne as Bob le Flambeur? Even if it means nothing at all, we can at least agree that it was very rare in the 50s for a director to have an actor, rather than an actress, dye his hair platinum, especially when the role does not specifically call for it? Marlon Brando’s blond hair in The Young Lions, for example, is not a distraction but an appropriate makeover, accentuating the character’s Germanness. Only Melville can tell us what he had in mind, if anything. But, until then that time, the undeniable resemblance is too breathtaking to ignore.

Separated at birth? Happy coincidence? Or payback?

Mark Rappaport

August 2006